Norwegian Viking treasures tour Europe

Viking relics found in Norway and elsewhere are expected to be viewed by exceptionally large crowds in London as the British Museum stages its first major Viking exhibition in 30 years.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Some of the first things you encounter when visiting the exhibition “Vikings – life and legend” at the British Museum are Norwegian jewellery.

The Vikings liked to adorn themselves, and that goes for more than Viking women. Men showed off their status with meticulously made swords and axes, both in times of peace and when they out battling and plundering.

The university museums in Oslo, Bergen and Tromsø have lent a large number of Viking artefacts to the exhibition which opens today in London.

These include a shield from the Gokstad Ship, oars from the Oseberg Ship, a gilded “weather vane” which once perched atop a ship’s mast as well as solid silver necklace.

“These are fantastic finds,” says Gareth Williams, the head British curator of the exhibition.

Viking trend

Attendance is expected to be high at the British Museum, which last year had 6.7 million visitors.

“Right now there’s a Viking trend and that will fuel a lot of interest,” says Williams.

Popular TV series such as “Vikings” have amplified the public’s fascination with the Viking Age.

The first comprehensive Viking exhibition at the British Museum in three decades is the result of years of cooperation among museums in three countries. After five months at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen last year, it is now the UK’s turn until 22 June. Then it will continue on to Berlin’s Museum of Prehistory and Early History.

The British Museum is also issuing a film of the exhibition which will reach out to a greater crowd than those who visit museums. It has also deployed its massive resources for lectures, cultural activities and production of souvenirs.

World’s longest Viking Ship

On display are also Arab coins, silver treasures and artefacts found in Russia which couldn’t be borrowed during the Cold War. With contributions from 25 exhibitors in a number of countries and just three halls at their disposal, the museum has managed to find room for a mighty selection of objects, modestly presented in glass display cases.

Quotations posted on the walls stem from the Icelandic Sagas and even Medieval Jewish sources, testifying to the many cultures which came in contact with the Vikings. Some were partners in trade. Others were drawn involuntarily into the Viking sphere as victims of war.

A key explanation for why the Vikings were so successful at attacking is found in the large exhibition hall.

Looming over visitors are parts of the longest Viking ship ever found, the warship Ægir, from Roskilde in Denmark.

It was 37 metres long and could carry 100 men.

“It must have been a chilling experience, watching this ship approach,” comments curator Thomas Williams. He has worked on the exhibition along with his colleague Gareth Williams.

The Viking ships in Oslo are so fragile that plans to move them to a prospective new museum on the other side of the city have been at least temporarily shelved. But the Danes packed their precious wooden remnants flat, more painstakingly than Ikea furniture, and shipped across the North Sea.

This was just 20 percent of the original ship, which was all the archaeologists managed to salvage during the excavation in Denmark’s form capital city Roskilde in 1997. After years of conservation efforts, the ship was initially exhibited in Copenhagen in 2013.

The struggle for Norway

The Ægir ship serves as a symbol for the Vikings’ prowess as seafarers. The exhibition circles around this Scandinavian need to expand, the encounters with new cultures, intercontinental trade and a good deal of the havoc they became known for.

The Viking Age reached its apex around 1025 AD. As they conquered kingdoms across the seas they amassed an empire.

This is when the ship Ægir was built in the Oslo Fjord, perhaps on the orders of the Danish King Knut.

“Knut ruled Denmark and England, and was on the verge of taking over Norway too. The construction of such an enormous ship would have proved that he meant business right after he gained power over Norway. But the ship can also have been built for Olav Haraldsson, St Olaf, as a means of stopping Knut,” says Thomas Williams.

Graffiti from Bergen

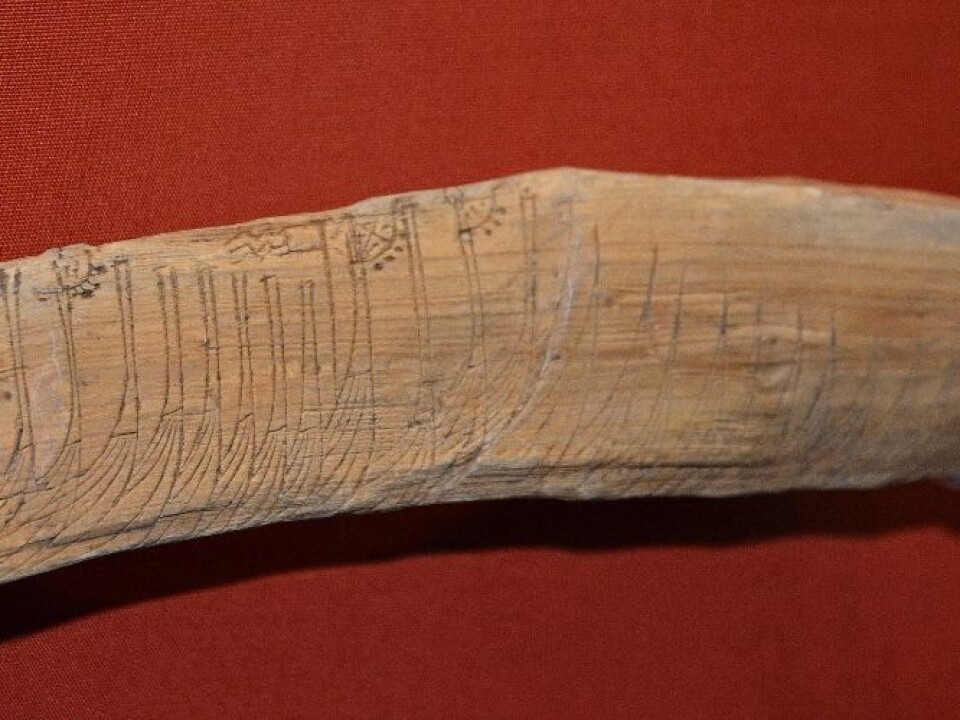

Among the mighty ships and gilded weapons is a little wooden stick from Bergen, one of the biggest cities in Norway, which is Curator Gareth Williams’s personal favourite.

“Drawings of Viking ships have been carved into it, sort of like graffiti,” he comments.

It is not from the Viking Age, as it stems from later into the Middle Ages. But it still says much about the Vikings, thinks Williams. The carvings depict a number of ships, perhaps a fleet. In conformity with the rules of the day, something Williams focused on in his PhD, the subjects of the king were expected to supply him with ships and crews when needed.

“The carving helps us imagine a fleet of warships, which the Ægir would have been a part of,” he says.

The wooden stick also has a message in runes, translated by the British Museum to: “Here sails the Sea-brave”.

“It is reminiscent of inscriptions from the Viking Age. The Vikings were poetic, not just murderers,” says Gareth Williams.

Violent society

Although the experts behind the exhibition sought to present a comprehensive and complex picture, they also wished to show the Vikings’ violent nature.

“We cannot ignore that they attacked monasteries and pillaged. The name ‘Viking’ actually referred to a pirate or the act of wreaking havoc. It was a job description. On the other hand, the reports of attacks were often made by the victims, so they are probably rather biased,” says Gareth Williams.

He has grown weary of the experts who only portray the peaceful sides of Viking societies.

“Until the 1960s, Vikings were seen as utterly violent. Then a shift in emphasis emerged and probably swung too far in the other direction,” he says.

“Here we are attempting to show both aspects.”

Nevertheless, in the publicity for the exhibition the museum has opted for a video of howling Vikings storming forth. Is that what is needed to attract the crowds?

“Most people identify the Vikings with violence. It’s tempting for us to exploit this,” explains Williams.

“But those who come for that reason only will be disappointed.”

First display of a mass grave

The filed-down front teeth on a Viking skull found in England exemplify how far the Vikings would go to scare their enemies. But they never had horns on their helmets, as they so often do in Hollywood portrayals.

Nor were the Vikings invincible. A new discovery shows how wrong things could go for them.

Part of a mass grave unearthed in Dorset, England, has never before been on public display – not even in the exhibition when it was arranged in Denmark.

The grave is the result of the execution of 54 Vikings.

“They have been decapitated and the heads were placed a bit away from the bodies. The execution would appear to be from a Viking raid that didn’t turn out favourably for them,” says Thomas Williams.

The Anglo-Saxons, who were probably behind those who killed the prisoners, appear to have been just as barbaric as the Vikings.

“Three heads are missing. They were probably placed on stakes as a warning to any other Vikings who entertained plans of attacks,” says Thomas Williams.

----------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling