Immigration in the Viking era

The stalwart peasant. Christianity. Ibsen, Grieg and the poet-priest Petter Dass. A glance at history indicates the Norwegian archetypes have immigrant backgrounds. So who are the Norwegians actually?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Knut Kjeldstadli of the University of Oslo has led a group a researchers who have studied Norway’s immigration history from the Viking Age up to the present. He says the tracks left by immigrants and visitors traverse the entire period.

“Irish slaves came in the Viking Age. And around the year 1000 another import came that was to have a huge impact on Norwegian culture: Christianity," says the history professor.

The kings brought along specialists in Christianising people. These were priests and monks from Germany and England. Even the Anglo-Saxon bishop and advisor – who canonised Olaf Haraldsson, was a Brit.

Thralls and careerists

Kjeldstadli points out that multiple groups immigrated to Norway in the Middle Ages.

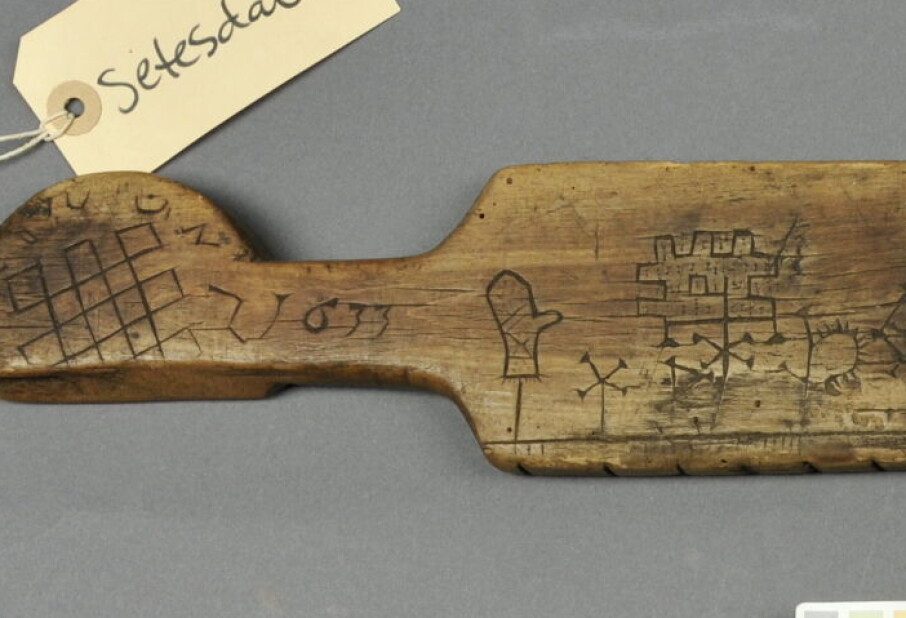

At the bottom of the social ladder were the Irish slaves, or thralls. They might not have had too much of an impact on the culture. Around 1250 the first refugees came from Russia. They had been pressed westward by Mongolian tribes.

But a number of career immigrants − specialists in various professions − probably had the biggest influence. Some followed in the wake of the new religion.

“The men of the church in this context were not just the priests and monks, but also stonemasons and other craftsmen,” says Kjeldstadli.

There was an influx of European noblemen who could be political refugees, as well as specialists like minters, physicians and building inspectors.

![Anti-Semitic grafitti on store windows in Oslo during the Nazi occupation in 1941. The texts read: “Jews – the parasite that brought us April 9th” [the date of the German invasion in 1940] and “Palestine is calling all Jews. We won’t stand for them any longer in Norway!” (Photo: Anders Beer Wilse (1865–1949)/Wikimedia Commons)](https://image.sciencenorway.no/1372597.webp?imageId=1372597&width=960&height=720&format=jpg)

“The royal powers saw an advantage in using foreigners. They had no domestic power basis and thus became dependent upon and loyal to the king," he explains.

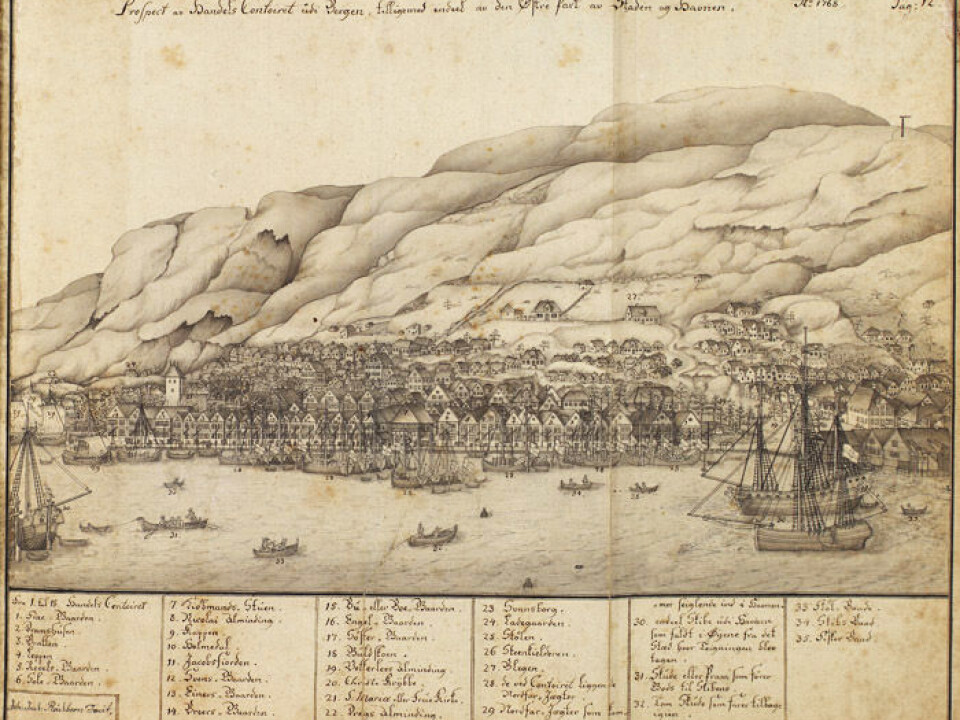

And of course there were the merchants. In addition to the powerful and influential Hanseatic League there were Scots and Dutchmen who contributed to keeping trade routes to the Continent and the British Isles busy. They brought knowledge of modern business and bookkeeping to Norway.

Some of these tradesmen settled down and became Norwegians. Roughly put, the Norwegian urban bourgeoisie consisted of naturalised foreigners, according to Kjeldstadli.

“Today we find many traces of these immigrant names in the telephone catalogues. Surnames such as Aubert, Bødtker, Friele, Hambro, Michelet, Mowinckel, Schreiner, Stang and Stoltenberg come from immigrant ancestors.”

Immigrant Scots were the origins of families like Grieg, Christie and Dass. The names Munch and Ibsen also stem from immigrant backgrounds.

Important immigrants

Researchers don’t know how many immigrants came to Norway during the Viking period and medieval times.

“We shouldn’t exaggerate the volume of immigration. It was doubtfully more than one percent of the population, but their impact is greater than their number,” says Kjeldstadli.

Lots of those who came were specialists and members of the elite. They had a significant influence on society and brought knowledge to the country which could only come through immigration.

Some immigrants played a local and regional role, such as the Kven people in Troms and Finnmark Counties in the north, and the Swedes in Østfold County.

A steady stream of lesser-skilled Swedes came to Norway from the 1700s along with the specialists that continued to arrive. They were mainly job-seekers from the lower classes who settled and became Norwegians. Even while Norwegians were emigrating to America, thousands of poor Swedes were immigrating to Norway.

“Around 750,000 emigrated from Norway before 1915, but at the same time 150,000 came here,” he says.

Skills learned from moving around

During the course of history and prehistory our genes and culture have been mixed with material from around Norway, Scandinavia, Russia, Central Europe and the Middle East.

See also: Immigration in the Stone Age

“We’d be a different country without the cultural contributions of people who came here,” says Kjeldstadli.

Much of the knowledge that was needed, for instance mine engineering and industry, couldn’t be put into writing and memorised. People had to move around for knowledge to be shared.

Norwegians left the country and brought knowledge back home again. And new skills came from foreigners who moved to Norway.

Not always without friction

The continuous mixing of people didn’t always go without a hitch. For instance, the import of Christianity was a bloody affair.

At times, immigrants have created big problems.

"In 1455 a group of Germans killed the King’s commander in Bergen, as well as the bishop and 50-60 monks and nuns. We also know there were violent conflicts between German miners and peasants in Telemark in the 1500s.”

In other cases it was the immigrants who were on the receiving end and were made into scapegoats.

There are stories of Swedish workers in Oslo who around the time of Norway’s dissolution from its union with Sweden in 1905 had to stick together in groups when downtown to avoid being beaten up by Norwegians.

Jews, Catholics, Protestant Kvens and Swedes have at one time or another been considered social threats.

"But most have been assimilated with the passage of time. Now we of course consider the descendants of these earlier groups of immigrants as Norwegians, and we no longer regard their cultural contributions as foreign," says Kjeldstadli.

He believes history will continue along these lines.

“The nation is a process, not a fixed entity. It evolves in the interface between those who live here and those who come. Cultural elements which were imported have become Norwegian. Some of the things we consider alien will be Norwegian in the future.”

The professor is not afraid of contemporary Norwegian values biting the dust.

“Values we believe should endure in Norway, such as freedom of speech and democracy, are not only cherished by the mainstream majority culture of Norwegians. Plenty of others also agree with these ideals,” says Kjeldstadli.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling