Tasting 16-day-old fish is just one of many tasks supertaster Kristin has done for researchers

Meet the supertasters on a normal day at work.

Josefine Skaret divvies up a cut of rump steak. Each piece has to be exactly the same size. The frying pans have to be exactly the same temperature. The pieces of meat must be fried in exactly the same amount of neutral oil for the exact same amount of time.

Skaret's job is to prepare food for taste testing at the Norwegian food research institute Nofima.

Researchers rely on many methods for their work. They study documents, interview ordinary people and experiment in the laboratory. At Nofima, ten taste testers are an important part of the institute’s research methods.

Josefine Skaret puts the pieces of meat into small plastic bowls and carries them in to ten taste testers who sit ready in their booths in the next room.

The room is bathed in bright red light.

One piece of meat – 26 properties

In today's test, the tasters are not supposed to assess the meat’s colour or appearance.

“That’s why we use red light in the test room, so that we camouflage the colour of the meat. It makes all the pieces look the same, and the appearance doesn’t affect the assessment,” says Skaret, who is head of the taste tester group. Or the sensory panel, as it is called in technical language.

The ten taste testers will assess a total of 26 different properties in the small pieces of meat.

How does the meat taste? Does it taste sweet, sour, salty and/or bitter? Don't forget the fifth basic taste: umami.

But it's not as easy as ticking off selections like bitter or salty. No, these arbiters of taste have to perceive tiny nuances. If they think the meat tastes sour, just how sour? How bitter does the meat taste on a scale of one to nine?

They also have to assess the smell.

Some of the smells they will judge are more common. How strong is the fried smell, for example? Other smells are strange. The taste testers must determine whether the meat smells musty, rancid, liver, metallic or of manure.

How much force, how much chewiness?

Unbeknownst to the taste testers, texture is the most important characteristic for this particular test. It is part of an international project where the researchers are looking at ways of tenderizing beef, among other things. They want to find out if different ways of handling the beef make it easier for the elderly to chew.

Skaret explains how the taste testers evaluate the texture.

“They must assess hardness, that is, how much force they have to use to bite through the piece of meat, and tenderness, meaning how many chews are needed to finely distribute the piece of meat in the mouth before it can be swallowed,” she says.

They also have to assess juiciness, how much liquid is left in the piece of meat after eight to nine chews, whether they have a sensation of fat in their mouth and how much of an aftertaste they have after 30 seconds without rinsing with water.

While the taste testers sit bathed in red light and smell, taste and chew, Josefine Skaret follows along on a screen. This is where the results come in.

10 women = 1 instrument

When everyone has finished tasting and smelling and chewing, they go through the test and the results.

“Our sensory panel is a research instrument,” Skaret says.

Like all instruments, it needs to be fine-tuned. Today was a pre-trial. In this case, the test consisted of only two pieces of meat that had been tenderized in different ways.

Skaret checks with the taste testers: Have they understood what they should smell and taste?

If there are large discrepancies in the results, they have to figure out whether it is because someone has a cold, or if someone has clicked on a result incorrectly or whether someone has misunderstood what a sour smell really is.

“We always have a calibration round, where we get the instrument to agree before we start with the main experiment itself,” Skaret says. The main test will be conducted the following day. During this round, there will be lots of different meat samples prepared using different tenderizing methods.

It smelled like manure

During this round, the results from the judges are relatively unanimous.

Several testers think the pieces of meat smell of liver and manure. Skaret explains that these are low-intensity smells. It’s not certain that an ordinary consumer will notice them.

“The testers are trained to be super sensitive,” says Skaret.

So you have to have to be a 'super smeller' to detect what the taste testers describe as an unhealthy, nauseating smell.

The taste testers find sour taste difficult, because ‘sour’ is too general. They have chosen to distinguish between sour as in fruit and sour as in meat.

One piece of meat had been tenderized in a brine of salt phosphate. The other was treated with microblades, which are used in tenderization. The blades cut tiny incisions into the meat.

So how did the texture and chewiness of the two cuts of meat measure up?

Easier with meat than with aquavit

The taste testers find that the meat that was cut with microblades was easier to chew. It felt more tender and juicier. But they notice that the piece of meat has been processed, without them knowing how. They agree that the structure of this cut seems less natural.

None of the judges find this test very difficult.

“But it can be demanding for your jaws if you are chewing a lot of meat,” Skaret says.

The week before, they tasted many different types of aquavit. This, it turns out, was much more difficult.

Kristin Enger is one of the taste testers. She has tasted and smelled food in the service of science for 17 years.

“Aquavit was very demanding, because it contains so many flavours and it’s got a very strong taste in your mouth,” she says.

The taste testers neutralize their mouths between each sample, either with water, biscuits or yoghurt. But it was hard to get rid of the aftertaste of the aquavit sips.

16 days old fish

Not all work days and taste tests are equally fun. One day they tasted fish that had passed its use-by date. One day, two days, three days and on for days and days.

After 16 days of storage at the wrong and bad temperature, the fish was no longer as fun to test.

“Then there was a lot of fish that was difficult to taste. I didn't have fish for dinner that week,” Enger says.

“It was a less than good day at work,” Skaret says.

One of the taste testers stopped eating salmon after that round.

“I taste a lot of things that I wouldn't eat in private. But it’s fine at work. Whether I like it or not doesn't matter here,” Enger says.

Chocolate is difficult

One of the first tastings Enger took part in was of rancid herring forcemeat.

“It was a challenge,” she says.

But otherwise it's been fine. You would think that chocolate tasting was the best, but that is not the case.

“It’s not easy to judge chocolate. There are a lot of strong, different flavours, and we need to detect tiny differences. Whether you like chocolate or not doesn't matter,” says Enger.

She thinks fruit is the easiest to test.

“It’s less demanding. Fruit is not that strong and there are rarely negative flavours. The fruit may be overripe, but that's not too bad,” she says.

The day they sat for many hours chewing raw onions was harder.

Personal taste does not matter

“Raw onions are so strong. We were supposed to describe crispness, sweetness and bitterness. But it was a completely normal day at work, and I have no idea why we did it,” says Enger.

The job as a taste tester is not about assessing how good the food is.

“Our job is to identify the flavours in the food. We quickly get used to not caring if we like what we taste or not,” Enger says.

“No matter what they are served, the taste testers assess it professionally and objectively. Of course, we don’t give them anything dangerous. Everything is tested, so it is safe to taste,” Skaret says.

The judges don't swallow what they taste. They spit it out, so they don't get full, because being full can affect their judgement.

As a result, their job actually starts at home.

Neither hungry nor full

Kristin Enger and her colleagues have to take many factors into consideration as they prepare for work. They can’t use perfumed shampoo, skin creams or detergents.

“We also can’t eat strong food or drink alcohol the day before a taste test. We can’t have any residual tastes in our mouths. We shouldn’t be full, but not hungry either,” Enger said.

They get an extra-long lunch break. After they have eaten, they have to wait half an hour before they can start tasting.

Enger thinks it's perfectly fine to live with these rules.

“We’re doing an important job. You don’t fool around with research,” she says.

Fruit-flavoured salmon

The test rooms are kept free from soap and perfume odours. But in the midst of the pandemic, the results suddenly started to be weird.

The taste testers tested raw salmon. One of the pieces of salmon tasted sour, and several of the judges noted that it tasted faintly of fruit.

“We didn't understand why,” Skaret says. They began to search.

It turned out that the fish laboratory had begun using a new type of alcohol to disinfect its premises.

“After a lot of searching, we found the new disinfectant, which smelled of fruit. It was this smell that the taste testers detected,” Skaret says.

The results of the tests are used by a number of people, often researchers who are trying out different methods for processing raw materials. Does the method affect smell, taste and texture?

Not told what the tasting is for

“Sometimes we are given assignments by the food industry. It may be a company that comes to us with a product that does not sell as well as the competitor's product. Then they come to us to find out why. We can survey the taste profile and the differences between the two products,” says Skaret.

Although the taste panel is an important research method at Nofima, the taste testers are rarely told about the results of the studies they’re involved in. At least not until much later.

“We can’t say anything about what the testing is about while it is underway. And when the results are ready, so much time has passed that the testers have almost forgotten that particular test,” Skaret says.

“Sometimes we get curious, but we don't get answers. We do the work and don't talk to each other about why we are tasting something or exactly what we are going to find,” Enger says.

Sometimes it's easy to figure out. Once they tested pizza with tomato sauce. Then their assignment was to scrape off the sauce and assess whether it had soaked into the bottom of the crust.

“We were supposed to check if the bottom got soggy,” says Skaret.

The work of the ten taste testers is not to be confused with consumer testing.

Training helps

The sensory panel describes objective characteristics of the food, Skaret says. This allows researchers to figure out how method A affects product B. For example, how a brine affects a piece of meat or how poor storage affects the taste of salmon.

“But we have to use consumer testing to figure out whether or not ordinary people will like the food or not. Our trained taste testers are no help here,” Skaret says.

The taste testers are, in fact, well trained.

They are tested with basic flavours at regular intervals. This way they can make sure their taste buds are still working as they should.

“This is a way to check that we haven’t changed over time,” Enger says.

This test involves giving them 32 small glasses of water, each of which has a faint taste of bitter, umami, salty, sweet and sour.

Super difficult test

“Some of the water glasses taste like nothing, but I manage with most of them. I have missed some of the weakest flavours now and then, but in these cases they have extremely little flavour,” says Enger.

It's not a problem if a tester has a bad test once in a while, but if the problem persists, they need to figure out why.

Two of sciencenorway.no's journalists were also tested on basic tastes, colour and smell.

First we got to taste labelled samples, so that we were familiarized with the flavours. Then the blind test started. All the flavours come in three intensities.

It was really difficult. Did the little sip taste salty or bitter?

We did quite well with sweet and the meaty umami taste. But the rest went badly. Very badly.

Not everyone can identify the smell of boar taint

However, we passed the colour test with flying colours. Full marks.

We both were also able to identify the taste of a substance called 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP). It's a horrible, bitter taste. Like cold charcoal in your mouth. But 30 per cent of the population cannot detect this taste at all.

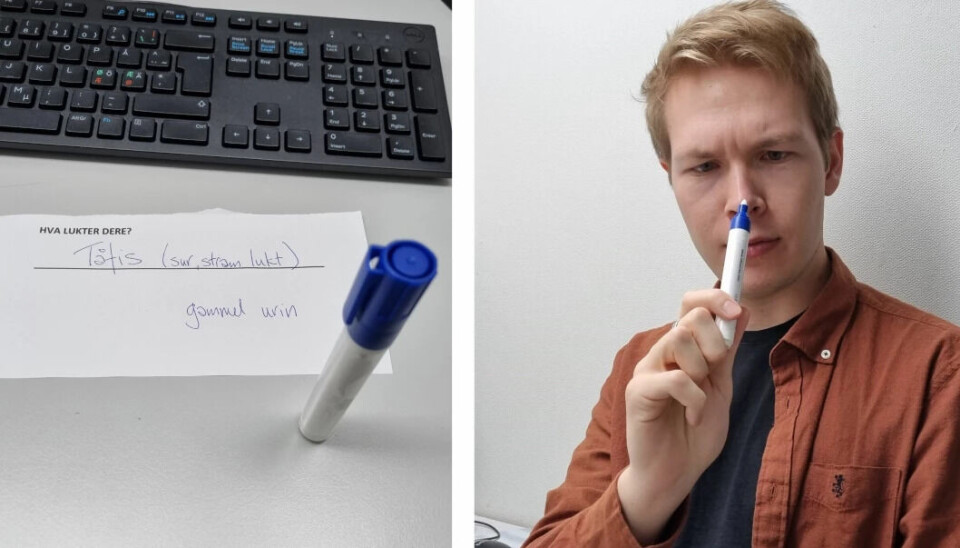

Then we were given a felt-tipped pen to smell and then describe. I myself wrote that it smells like toe jam and old urine. Journalist Anders Moen Kaste didn’t smell anything at all.

He went straight into crisis mode. It doesn't feel good to smell nothing when your colleague almost vomits from the stench.

One of us smelled a sour, pungent smell. The other didn't smell anything.

“Were we given the same test?” he asks Josefine Skaret. She confirms that the samples are the same.

But she can also calm him down. The sample was the smell of boar taint, an odour from the meat of male pigs that have not been castrated. Just as with the PROP taste, a proportion of the population is genetically predisposed not to recognize the smell of boar taint.

The sciencenorway.no journalists would not have be given jobs as arbiters of taste.

Just a little different than the others

Kristin Enger was not aware that she was a supertaster until she was tested when she applied for a job at Nofima.

“I had never thought about it. But I have always been extra sensitive to smells and tastes,” she said. “I noticed sooner than the rest of the family that the liver pate in the fridge had been open for three days.”

The other taste testers also described episodes from their childhood and youth. They were more sensitive than the rest of the family. One of them smelled fire long before the others noticed anything. Several have been called quirky and picky.

“But even though we are sensitive, we are not picky,” says Enger.

The job as a taste tester gives Enger some advantages at home. It’s easier for her to balance flavours and spices.

“I like to cook, but I'm not a super cook. But I am careful about balancing sauces. Then I can use my taste skills,” she says.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no