People don't want plastic around their food. Here’s how researchers can solve this problem.

Several approaches are being studied. Fish scales can be made into plastic, or we can go back to paper and cardboard.

Consumers have become more and more unhappy about food being packaged in plastic.

In France, plastic packaging for vegetables has been banned. A number of surveys show that consumers in many countries, including Norway, want less plastic around their food.

But plastic isn’t so easy to replace.

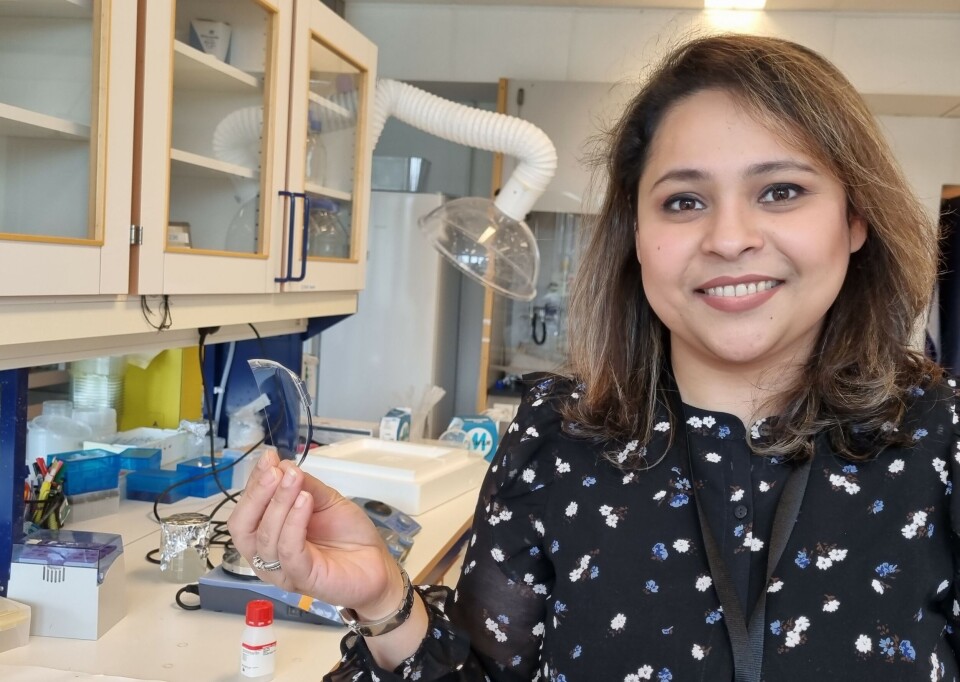

“What worries us about plastic is that not everything in the plastic breaks down. If we can replace these components of plastic with other materials, then that is one solution. I am working on that,” says researcher Nusrat Sharmin at Nofima, the food research institute in Ås.

Sharmin is looking for materials that are not eaten or used for anything else. Now she is working with fish scales.

“We don't eat fish scales, or fish bones or much of the skin,” she said to sciencenorway.no.

From fish scales to plastic

Fish scales contain the protein collagen. Sharmin makes gelatine from this collagen. The gelatine can then be used to make plastic.

“The gelatine from fish remains doesn’t have the same properties as other gelatine on the market. So I'm working to make it better,” Sharmin said.

If the researcher is successful, the fish-scale plastic will still not be able to be used on all foodstuffs.

“It will probably be better for some foods, and not for others. We will test it on cheese and fruit. I think the fish plastic could be good for salmon,” she said.

Spent three months on plastic film

Sharmin often starts her research efforts by using the food itself as her starting point.

“For example, we can look at what strawberries need in terms of packaging and then make plastic with exactly the properties these berries need,” she said.

She’s now in the initial stages of her research project. She has struggled to make plastic wrap out of the fish gelatine. She’s trying to create the same type as is used in home kitchens to cover food.

“For three months I worked on making a film, but I didn't manage. Then we changed the method, and then I was able to do it,” she said. “80 per cent of our attempts end in failure. That's just how it is when you work with materials. But we continue with the 20 per cent that work out.”

Rosemary and seaweed for bioplastic

Sharmin was educated as a materials engineer, a discipline that is all about understanding materials — how they are put together and what they can be used for.

She also works with other materials that might be suitable to use in plastic, such as rosemary and seaweed.

“Seaweed is cheap and has useful properties. And we have a very long coast in Norway, which is full of seaweed,” she said.

The researchers dry the seaweed, grind it up, put it in various chemical solutions, run it through various machines and mix it with other materials.

“This is good for the circular economy. Now we have to use everything,” Sharmin said.

Back to cardboard and paper

Many researchers across the globe are looking into different materials that can be used to make bioplastics. Sharmin thinks that fish, herbs and seaweed offer the most promise. Other researchers are pursuing cellulose, corn or sugar. Still others are looking into chemicals that do a better job breaking down plastic, or microbes that eat it up.

Kloce Dongfang Li at Nofima studies cardboard and paper. But it’s not easy to completely replace plastic’s good properties, because plastic is important in avoiding food waste.

“Plastic provides a good barrier against oxygen and moisture,” Li said.

Grocery stores often package meat and fish in plastic tubs covered with plastic film. The packaging contains a gas that inhibits unwanted bacteria and shuts out oxygen. The gas also increases the shelf life.

“But it is possible to replace plastic with cardboard and paper packaging for some food products,” Li said.

Cardboard plus a refrigerator provides good shelf life

In the end, the nature of the food is what determines which packaging works best.

“Take cucumber, for example. A cucumber wrapped in plastic will keep for two weeks. Without wrapping, it lasts for a couple of days,” Li said.

The refrigerator can be the saviour.

“Cardboard and paper packaging may not have the same good properties as plastic, but the right temperature in the fridge means that the shelf life of some food products can be just as long,” he said.

Paper and cardboard work best on fruit and vegetables, because they don’t contain much moisture on their surface.

At Nofima, the researchers tested tomatoes.

“If we store the tomatoes in the fridge, we don't need plastic at all,” Li said.

Cardboard plus plastic is a problem

He thinks plastic is a good alternative, as long as it is recycled and reused.

In Norway, only 30 per cent of plastic packaging is recycled. Approximately 540,000 tonnes of plastic are thrown away each year. This is an average of 101 kilograms per person, according to the Norwegian Retailers’ Environment Fund, an organization financed by a fee on plastic grocery bags.

But much of the packaging is a mix of both plastic and paper. And that creates problems. The cardboard cups we drink coffee from, for example. The cups are made of cardboard, but have a thin film inside which serves as a barrier against the liquid.

“It’s a challenge to recycle cardboard cups. Today it’s not possible. It’s impossible to separate the plastic from the paper, so the cups have to be burned,” Li said.

Mushrooms are best in paper

In a new project that Li is working on, researchers are trying to make plastic film that can be removed from the cardboard.

“Then consumers can separate the cardboard from the plastic at home, before they throw it away. But this depends on people being willing to do the work,” Li says.

He also works with chicken, vegetables and mushrooms.

Many shops have paper bags for loose mushrooms, but if you buy ready-cut mushrooms, they are packed in plastic tubs with plastic tops.

Li and his colleagues have studied whether it was just as good to pack them a paper tub. And it was.

“But the tub still has plastic film over it, so that the customers can see the product they are buying and the mushrooms don't dry out so quickly,” he said.

Plastic that looks like paper

The question of plastic or paper is not just about grocery stores. Kloce Dongfang Li studies the entire food chain, including companies that make the packaging, those who produce the food and those that sell it.

The Coop, a Norwegian consumer cooperative that includes supermarkets, has created its own packaging strategy, which includes reducing the use of plastic and using recyclable packaging instead. Knut Lutnæs, from the Coop’s communications department, says the company has come a long way.

The Coop also has packaging that looks like paper but is made of plastic.

Several manufacturers make this type of plastic. It can confuse consumers.

“We understand of course that not all packaging solutions are optimal,” Lutnæs wrote in an email.

“We want to make clear that this packaging is marked correctly, in this case with the symbol that says it should be sorted as plastic. We have confidence that customers will sort their packaging in line with the labelling,” Lutnæs wrote.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------