Innards are out

Norwegian dinner tables used to include dishes made of hearts, lungs, liver and kidneys. Today such innards are no longer eaten.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Just a few decades ago, Norwegians ate just about everything an animal had to offer, from pork kidneys to chicken’s feet.

If you compare a cookbook from the 1950s with one more recently published you’ll notice huge amendments in the chapter on meats.

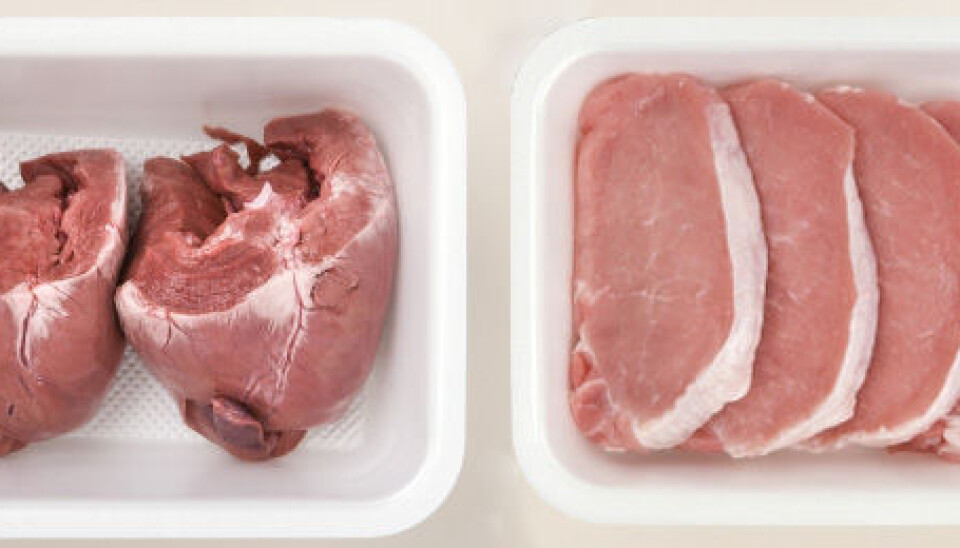

The older version featured lots of innards, and why they are good for us, and showed detailed pictures of the various edible parts of animals.

Today’s cookbook doesn’t include any photos of such innards, and they’ve also been stricken from the text and recipes.

Now such parts are mainly only used to make dog and cat food.

Distanced from our food?

Kristian Bjørkdahl is a research fellow at the University of Oslo’s Centre for Development and the Environment.

He recently lectured at a conference in Oslo regarding ethics and animals, where his topic was why Norwegians no longer eat offal.

He thinks we’ve become more alienated from the food we eat. We are in denial and cover up the fact that we slaughter other living creatures for consumption.

“We find it hard to deal with the thought of killing an animal and eating it,” says Bjørkdahl.

Bjørkdahl has several theories about why we are no longer fond of innards. His main focus is that the number of active farms has dropped in Norway and the remaining ones are further apart.

“The migration to urban areas has changed the relationship we have to our food. We only see meat in the shops and it’s displayed in ways that give little association with an animal carcass.”

He thinks if the food were presented as hearts and lungs and kidneys it would remind us that these animals have the same organs we do − and we’re the cause of their deaths. We could never consider killing a pet because it’s an animal we’ve established ties to.

“We’re alienated from the notion of raising and caring for an animal and then killing it.”

Poorer times

Bjørkdahl points out that innards were food items until Norway became a wealthy country and we no longer need to eat the entire animal, because we can afford not to.

“Industrialisation has created a distance to the animals as consumers we have a cleaner conscience when we opt for minced meat, which cannot be visually linked to any animal, rather than a leg of lamb.”

Bjørkdahl says we conceal the fact that animals are conscious beings, and he thinks the way we approach the issue of eating them is neither honest nor correct.

He thinks tension is caused by the diverse roles that animals play in our everyday lives. When we eat animals, clothe ourselves in parts of them, conduct research on them and are entertained by them, while simultaneously having them as pets, there’s a contradiction that causes confusion and we’re not sure how to handle the situation.

The traditional image we have of the Norwegian meat industry involves happy farmers with cute lambs or goats. In commercials and ads the cattle and cows look happy and we forget that these are the animals we actually eat.

“As consumers we’ve constructed differences between killing, slaughtering and hunting for animals. Yet these all come down to essentially the same thing, we kill the steer we eat,” says Runar Døving, a researcher at the National Institute for Consumer Research.”

He says children aren’t being informed of how their food is produced. School class visits to farms don’t give the right picture of what actually happens.”

“The children should be taken to slaughterhouses,” he says.

----------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling