Can animal bones become food for humans?

Researchers in Bergen on the west coast of Norway lowered animal bones into the sea to create more sustainable food.

Antonio Garcia-Moyano opens a heavy, white metal door into the laboratory. A cold stench of salty, rotten odour rolls over us. It is reminiscent of seaweed at low tide.

On a steel bench are plastic boxes full of bones. The cattle and turkey bones have a white coating with a slight green tinge. They are under attack from microbes.

Seawater flows into the boxes through plastic hoses to mimic ocean currents. The excess water flows out through holes in the bench in the lab at the research centre NORCE in Bergen.

“We wanted to find out more about the enzymes these organisms secrete, which make them capable of breaking down bones,” microbiologist Garcia-Moyano tells sciencenorway.no.

Lots of waste from meat production

Meat production produces a lot of waste in the form of bone remains. But now food producers want to be more sustainable.

If more of each slaughtered animal can be utilised it will be a win-win for the environment and food producers.

Not only will there be less waste, but the food industry can also sell more of the raw materials if they succeed in making more protein-rich food products for humans.

Making food for humans is more profitable than animal feed.

Rich protein source – can become a protein shake

The goal is to find new ways to utilise the nutrients from bones for use in protein shakes or the like.

Bones are in fact a rich source of protein. The challenge with bones of course, is that they are so hard. They are also difficult to dissolve while at the same time retaining the nutrients.

Enzymes that break down bone matrix already exist in the industry.

“But this technology is not favourable enough,” Garcia-Moyano explains.

The problem is that it is too slow and becomes too expensive.

Bones contain collagen, which is difficult to break down since collagen chains are very dense. They are also covered with various sugar molecules and mineral crystals.

Want to utilise more of the animals for human food

Today, most of the meat from chicken, turkey, pork, lamb, and beef is used for human consumption.

The rest of the soft parts, such as connective tissue, tendons and intestines are minced and used for animal feed.

Bones are ground up for use as fertiliser or in animal feed. They can also be cooked into gelatin, for use in sauces, desserts and cakes.

But otherwise, bones are used only to a small extent for human food.

“It is more demanding to make human food from bones,” Garcia-Moyano says.

This is a bottleneck in biotechnology.

Food producers are therefore on the lookout for new technology that can utilise more of these resources for food.

Left animal bones on the seabed

To find out more about which microbes in the ocean break down bone mass, researchers at NORCE in Bergen collected a lot of bone remains after slaughter.

In 2017, they lowered pots with turkey and cattle bones 60-100 metres down in Byfjorden off the seabed in Bergen.

“They lay there for up to six months before we brought them up again,” says Garcia-Moyano.

The bones showed clear signs of ‘attack’ by microorganisms that were in the process of dissolving them.

Next, the researchers embarked on painstaking analyses in the laboratory.

They hoped to find more enzymes that speed the process up.

Now their hunt is about to yield results.

A mixture of enzymes

Bacteria in the sea and bacteria that live inside animals are attracted to shiny bones on the seabed. These microbes contain enzymes that break down the bone matrix.

In addition to bacteria, there are small worms that are also tempted by the bones.

“Through analyses, we have arrived at a unique mixture of enzymes that degrade bones more efficiently than other enzymes individually,” Garcia-Moyano says.

This cocktail of enzymes has a greater effect than individual enzymes when it comes to breaking down bones, he explains.

Had to reproduce them in the lab

The enzymes' ‘teamwork’ speeds up the breakdown of bones. Some of them also break down sugars.

Once they had identified the enzymes that caused the degredation, they had to try to produce them in the laboratory.

The researchers presented the results in the Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal earlier this year.

The industry is showing interest

Their findings have aroused interest in the industry.

But there is still a lot of work to be done before the enzymes can be put to use.

In nature, this is a slow process, partly because the sea is so cold. It can take decades for bones to break down completely.

At higher temperatures, decomposition is faster.

“Now we have to try to optimise the process, so it’s faster,” says Garcia-Moyano.

Amongst other things, they will try to increase the temperature to 50-60°C to see if the enzymes can tolerate it. The enzymes may need to be adapted.

This will lead to new rounds of research by the team.

Sports nutrition

There are several examples of the industry relying on enzymes to extract raw materials from both fish and meat in Norway.

Norilia, a subsidiary of the food manufacturer Nortura, is one of several such players.

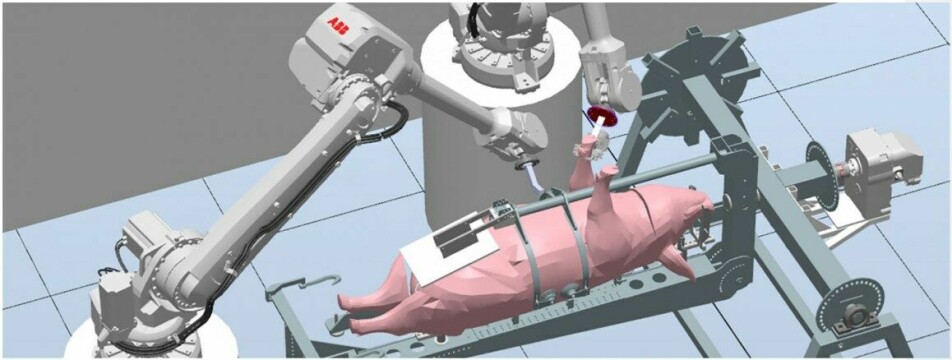

They have a new, modern biotechnology facility in Hærland for hydrolysis of the bone matrix of chicken and turkey with enzymes.

They currently sell ingredients for pet food in Norway and export some protein supplements to humans.

“We are also working on developing a ‘sports nutrition concept’,” says Heidi Alvestrand, head of business development at Norilia, to NORCE.

Residual waste can have an increased value

Antonio Garcia-Moyano has no doubt that residual waste from the meat industry has potential in the long run.

“Now such residual products have a low market value. If we manage to accelerate the decomposition, this will be an important contribution to the circular biobased economy,” Garcia-Moyano believes.

The enzyme cocktail can ensure that more of the animal is utilised in human food, and help the industry get more value out of the residual raw materials.

The study is a collaboration between NORCE in Bergen, Spain's public research institute CSIC Institute of Catalysis, and the German marine research institute GEOMAR in Kiel. Nortura has contributed bones.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Reference:

Fernandez-Lopez et al. The bone-degrading enzyme machinery: From multi-component understanding to the treatment of residues from the meat industry. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, Volume 19, 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.11.027