Norway could make Europe less dependent on critical minerals from China

Norway has large deposits of some rare earth metals that are important for the green shift. The Fen Complex fields in Telemark probably constitute a world-class deposit.

The war in Ukraine has shown us that becoming too dependent on a country ruled by dictatorship is a risky and vulnerable business.

Similar concerns are now growing about how dependent we have become on China and the country's strongman Xi Jinping when it comes to rare minerals.

China accounts for 80-plus per cent of numerous metals that have become essential for modern technology in the world.

The green shift, in which we switch to more renewable energy solutions, multiplies our dependence on many such materials, says Karl Kristensen, a consultant for Bergfald Environmental Consultants.

He gave a lecture on this topic during the recent KÅKÅnomics economics festival in Stavanger.

“We’re not only becoming dependent on more minerals, but we’re going to need dramatically larger quantities of them,” he says.

Kristensen points to rare earth metals as an example.

Rare earth metals have important functions as super magnets in electric cars and wind turbines, for instance.

“For the most part, only China has the technology to produce these components. This gives them almost complete control of the market for rare earth metals,” he says.

Telemark could save the situation

Elements and minerals are unevenly distributed around the world.

Norway and Sweden have considerable deposits of many minerals.

Norway has the Fen Complex (Fenfeltet), located at Ulefoss in Telemark’s Nome municipality.

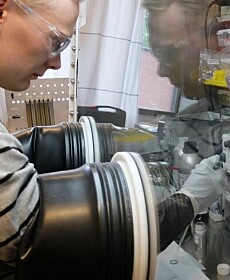

Geologists from the company Rare Earths Norway are now in the process of completing their second drilling campaign there this year.

“The preliminary results are positive and we’re encouraged to continue this extensive and resource-intensive mapping work,” says Trond Watne, a geologist for Rare Earth Norway.

Geologists from Vestfold and Telemark county have concluded from earlier mappings that this area contains very large deposits of rare earth minerals. The recent drilling on the field confirms those initial findings.

The Fen Complex has the largest known deposit of carbonatite in Europe, according to Watne.

“Most important for us is that the deposit contains a significant proportion of the highly critical, magnet-related rare earth metals neodymium and praseodymium that are needed to electrify Europe,” he says.

Probably a world class deposit

Light, rare earth metals dominate in the Fen Complex. Watne believes this is likely a world-class deposit.

However, he does not think covering all of Europe's needs with underground mining and responsible mining is realistic.

Many challenges need to be overcome before the field can become operational.

Even so, Watne has great faith that they will succeed.

“We’ve started an exciting research project to develop process technology adapted to the deposit. This is extensive work that also involves two university environments, NTNU in Trondheim in Norway, and Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, as well as the rare earth mining consulting company Carester in France.”

Rare Earths Norway has also been recognized by the European Raw Materials Alliance and has been granted an innovation loan by EIT Raw Materials.

Mining is controversial

“We know that mining in Norway is always controversial,” Arne Petter Ratvik said in 2021. He is a senior researcher at SINTEF and is coordinating a project to supply Europe with its own metals.

And we know that mining has environmental costs.

The Chinese extraction of rare earth elements has led to major environmental and health problems in the areas around the mines, according to news sources including the Los Angeles Times.

Recycling can help

Another possibility for responsible mining exists that is not currently being practised.

That would be to establish a well-functioning recycling industry that collects raw material waste that we currently discard and separates out the raw material so that it can be used again.

Phosphorus is an example of a raw material that could be recycled, says Kristensen.

This raw material is an important component of artificial fertilizers and is critical for all plant growth. Many people fear that a failure to meet the world's need for phosphorus could trigger a global famine.

The technology to recycle phosphorus already exists, but up to now we have not chosen to use it on a large scale.

Could have prevented food crisis

Kristensen explains that the process is quite simple.

“When we deliver food waste to a biogas plant, we end up with a bioresidue that contains all the phosphate that the food originally contained. When this is circulated back into the agricultural industry, we create a closed loop that makes us less dependent on imports of phosphorus from Russia or other countries with phosphorus reserves.”

Kristensen believes phosphorus could be recycled much more actively than has been done.

“We could have invested in infrastructure and value chains that would have solved this problem. Now we’re facing a possible food crisis in a lot of countries around the world because the price of fertilizer has risen so much,” he says.

No Norwegian policy

The USA, Japan, the EU, South Korea, Canada, Australia and Russia have drawn up strategies for the supply of critical raw materials.

Norway currently does not have its own policy in this area. The government plans to present a mineral strategy before Christmas, and anticipation about what it will contain is high.

“We need national strategies to deal with rare earth elements,” says Kristensen.

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, warned of the risk of becoming as dependent on China as Europe has become on oil and gas from Russia. In a speech in mid-September, she announced the launch of the European Critical Raw Materials Act to be presented at the beginning of 2023.

The European Commission now appears to be increasing the pace of its efforts to become more independent from China. This could increase the pressure on both the EU countries and Norway to recover more of today's metal resources and go in search of their own natural resources in Norway and Sweden.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no