World food production depends on phosphorus. Are we about to run out?

For the past decade, scientists have warned that phosphorus reserves are running low. Are we heading towards a crisis?

The plants and cultivation methods used by modern agriculture are entirely dependent on fertilizers, where two of the most important components are nitrogen and phosphorus. Nitrogen fertilizers can be produced in factories and are in practice a renewable resource.

But the same is not true of the phosphorus in fertilizers.

Currently, phosphorus is mined from rocks that contain the substance — called rock phosphate — that are mined in a few places around the world, especially in China and the Moroccan-occupied territory of Western Sahara.

And these resources cannot last forever.

Some predict just decades left

In 2008, some calculations predicted that the world would begin to experience scarcities of rock phosphorus as early as 2030. The consequence would first be dramatically increased fertilizer prices, and gradually declining crops.

In recent years, scientists have regularly sounded warnings of a looming crisis. In 2019, for example, the British newspaper The Guardian wrote that we only have a few decades of consumption left.

But the information on the topic can be confusing.

Others say 2000 years

Representatives from fertilizer producers themselves do not foresee any crisis.

“We have enough phosphorus for at least 2000 years at today's levels of consumption,” wrote Anders Rognlien from Yara, a fertilizer manufacturer, in an opinion piece in the Norwegian national newspaper Aftenposten in 2010.

Some researchers agree.

For example Pedro Sanchez, a researcher at Columbia University in New York, was quoted in a 2013 blog post as saying, “In my long 50-year career, once every decade, people say we are going to run out of phosphorus. Each time this is disproven. All the most reliable estimates show that we have enough phosphate rock resources to last between 300 and 400 more years.”

So is there a crisis or not?

Eva Brod, a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO) studies phosphorus in agriculture. So does Professor Petter Jenssen at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU).

They both conclude that we’re not about to immediately run out of phosphorus.

Nevertheless, they agree we need to do something about it.

More than 250 years

“The latest overview of the world’s phosphate reserves was conducted by Håkan Jönsson at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences", says NMBU’s Jenssen.

“His assessment shows that we have more than 250 years at current levels of consumption.”

But these kinds of estimates are often uncertain. They give an indication of the size of the deposits where rock phosphate is currently being mined, and the projections are based on how much phosphorus can be extracted using current technology and at a reasonable cost.

However, that doesn’t mean these are the only sources of rock phosphate. There may be many reserves elsewhere on the globe that are not being mined because they are more inaccessible, are less concentrated or are of lower quality.

Toxic and radioactive

“For example, a lot of rock phosphate is contaminated with cadmium or uranium,” says Brod from NIBIO.

If phosphorus from these kinds of sources is to be used in fertilizers, it must first be treated so that the soil is not contaminated with heavy metals or radioactive substances. It’s too costly right now for this kind of decontamination to be worthwhile.

But if the best rock phosphate begins to run out — and technology evolves — lower quality sources may suddenly become of interest nonetheless.

That means that agriculture will still have access to fertilizers, but farmers will have to pay more for it. And this extra cost will be passed on to consumers, so we will have to pay more for food.

Mined in just few places now

“A rich country like Norway will not have trouble getting enough phosphorus,” at least not the way things stand today, Brod says.

However, it is worth noting that the world's reserves of rock phosphate are very unevenly distributed, from a geographical standpoint. By far the largest reserves are in Morocco and the occupied part of Western Sahara.

“Europe and India have no viable phosphorus reserves as of today,” Jenssen says.

“We are consequently dependent on imports, and only China and Western Sahara have large quantities to export. China has introduced an export tariff to ensure they have enough for domestic use,” he said.

Thus, if major events such as war or conflict affect these areas, the world may still have trouble obtaining enough phosphorus.

A number of reasons to change

This is one reason why the world might need to look for other ways to meet the need for phosphorus, even if there is no immediate crisis.

And it's not the only reason.

Today's use, for example, is not sustainable forever, even though there might be as much as 2,000 years of rock phosphate reserves.

The environment is also an issue. The release of nitrogen and phosphorus from agriculture leads to significant pollution of waterways across the globe.

So what should society do? Where can we find large enough deposits of phosphorus?

The answer is surprisingly trivial.

Do like nature does

Nature deals with phosphorus by recycling it. That’s what we should do too, the researchers say.

“It’s important to remember that phosphorus is an element. There's plenty of it on Earth, and it never truly disappears,” Brod says.

This element — along with others — are necessary building blocks in the cells of all living beings.

Plants absorb nutrients in water from the soil and build them into their cells. Then animals obtain the substances by eating plants or other animals.

But the phosphorus is not used up. Both animals and plants constantly return phosphorus and other nutrients back to the soil through excrement and dead tissue.

In this way, a forest or natural field is fertilized all the time, so that it never runs out of phosphorus.

Manure, garbage and sewage

But agriculture is a different matter. Here we remove plants — and their phosphorus — from fields every year. The soil loses a little phosphorus for every crop that is harvested. Instead of returning the nutrients back to the soil, we deposit them elsewhere — in manure pits, in food waste, in sewage, or in the sludge from a fish farming facility.

Brod and Jenssen believe these resources contain more than enough phosphorus to meet the needs of Norwegian agriculture — if we could only find good ways to return these nutrients to farmers’ fields.

Long and heavy from manure pit to field

"As things stand today, recycling and reusing these resources is not practically possible", says Brod.

“For example, one challenge is that livestock production takes place mostly in western Norway and along the coast, while the need for phosphorus is greatest inland,” she says.

Livestock manure contains a lot of water, and it is expensive and impractical to transport it very far. And farmers don’t necessarily have the equipment to use manure instead of fertilizer.

It is also no easy matter to use sewage as fertilizer. Today's purification processes for cleaning sewage sludge make the phosphorus in the sludge difficult for plants to use.

In order to achieve solutions that work in practice, animal manure, sludge from fish farming and sewage from humans has to be processed.

But it's not just a matter of drying the waste and using it as fertilizer, says Brod.

“Different types of treatment alter the quality of the phosphorus, and heat treatment is not that good,” she said.

These processes can also be expensive and require a lot of equipment and energy. But that may change in the future, the researchers believe.

Bacteria can capture phosphorus

“We are just at the beginning phase of studying phosphorus recycling,” says Jenssen.

But things are starting to happen.

“NMBU has several projects underway, including processing waste from food and toilets,” he said.

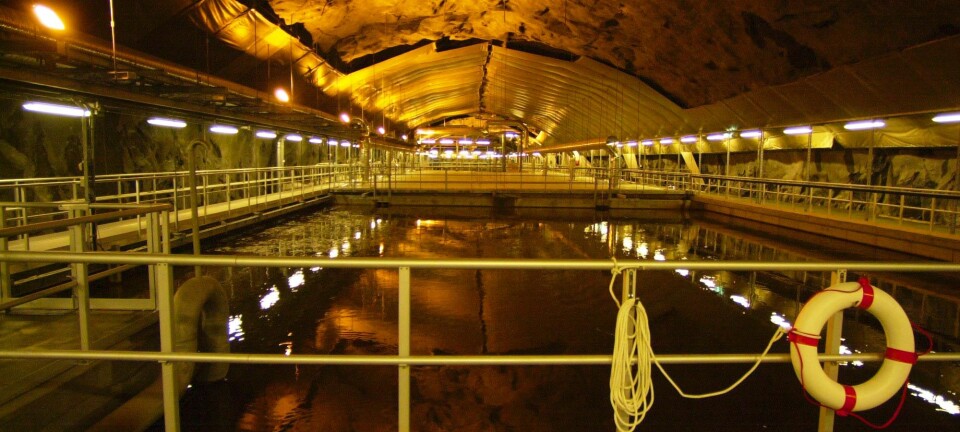

"And a treatment plant HIAS in Hamar has been a pioneer in recycling phosphorus from wastewater."

The Hamar treatment plant captures phosphorus in the sewage using bacteria. The bacteria absorb and concentrate the phosphorus so that phosphorus fertilizers can be made in solid form. These fertilizers can be applied to fields with the same equipment used to apply today’s fertilizers.

“I think this model will be used by many countries and industries, in Norway and internationally,” says Jenssen.

He says that attempts are also underway to use algae in the same way: The algae can grow on our waste, and then we can use the algae for, for example, fertilizers or fish feed.

Great interest in recycling

Jenssen also believes we will someday have toilets and sewerage systems that make it easier to extract nutrients from our waste.

“Vacuum toilets are being used in new apartment blocks in an EU project that NMBU and NIBIO have in Fredrikstad,” Jenssen says.

A similar effort is underway in Hamburg, Germany.

“That makes it easier to extract resources from faeces and organic household waste. These products can be transformed into both biogas and fertilizers, something we are working on in the EU project,” he said.

Jenssen says that there is great interest in recycling and reuse of nutrients from wastewater, but researchers are still at the starting phase of studying how best to do it. Currently, only a few solutions are profitable enough to compete with fertilizers.

But that can change quickly as the best rock phosphate reserves disappear. Or sources of other nutrients, for that matter.

Fields need other nutrients, including potassium and sulphur.

“We rarely talk about the fact there may also be shortages of these substances,” Jenssen said.

Nevertheless, “even though it doesn’t look like we are immediately facing the horrifying scenario of running out of phosphorus, there’s no reason not to focus on recycling,” he said.

“We need political approaches to make sure that we use the phosphorus we have in a better way. Then there will be no crisis,” Brod said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no