Scientists spread dubious number on debris in seas

Researchers have often said that ten percent of all the plastic manufactured ends up in the oceans. Where did they get that number?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

It is tempting to beat our largest drums when fighting pollution. We know that our planet’s environment is seriously threatened on many fronts and solutions need to be found quickly. Unfortunately, we don’t often know how much damage is being done.

One of science’s cardinal virtues is accuracy. Despite that, scientists are contributing to the dissemination of numbers with rather nebulous sources.

When ScienceNordic’s Norwegian partner forskning.no recently wrote about new calculations quantifying the plastic debris in the sea, we wondered why the new figures were so much lower than previous findings.

A number of researchers stated that the new calculation methods were the best they had seen to date. So we tried to find out how other scientists had ended up with a much higher figure –ten percent of the world’s plastic output. This was no easy task. The one-tenth figure cropped up ubiquitously, but no one could say what research it was based on. Apparently it didn’t come from research at all.

Wave of plastic

Some still claim that ten percent of the plastic produced annually ends up in marine environments. In 2013 alone that would equate to 30 million tonnes. This is a staggering amount of plastic for the oceans of the world and the marine life in these seas to cope with.

The latest calculations decrease this share of plastic debris to two to four percent of annual output.

We started searching for the source of the ten-percent figure.

Pick a number

Each reference pointed to another, which in turn referred to another article or paper in an apparent endless chain. Where was the original source?

“I was irritated. When we found there was no basis for it, we stopped using the number,” Inger Lise Nerland

A UN document for a workshop of international experts on marine debris also referred to a scientific paper. But when we checked that paper there we found no trace of this ten percent estimate.

We contacted the Secretariat of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, which had commissioned the document from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). They would not put us in touch with the author of the document, but Jihyun Lee in the Secretariat sent us an e-mail:

“Our consultant quoted the reference in good faith as it was cited in a peer-reviewed paper as being the source of the information. A robust review of this paper by the consultant when he quoted this information could have avoided this mistake. Unfortunately he did not go back to the source reference in this case to double-check the original source.”

UN removes the number

The UN document was a draft. The mistake had already been pointed out by a scientist at the workshop and checked out. Jihyun Lee explains that the number will now be deleted from the final report.

But the number had already spread internationally, including to Norway, where the expert on plastics Geir Wing Gabrielsen of the Norwegian Polar Institute quoted it in the media.

“When I read a scientific article or a UN report, I expect the references made to be correct and they should be possible to confirm. It is unfortunate when, as in this case, numbers are impossible to track down,” he writes in an e-mail.

Gabrielsen conducts research on how plastic pollution impacts a seabird known as the northern fulmar. For him, the amounts of plastic in the oceans represent only a background figure.

“For me, as a researcher on plastics as a problem for the fulmar, the exact quantities [in the oceans] are not so important that I need to get them verified.”

Unending swirl of quotations

As forskning.no attempted to track down the number from the UN report it turned out the consultant hired by the UN to write the draft had probably never read the reference (Wright) he referred to. Let’s call this draft article 1. He quotes article 2 (ET&C Perspectives), which again quotes article 1, where the number cannot be found.

But the author of article 2 has quoted the wrong article. He thanked us for bringing this to his attention and says he should have been more accurate. He refers us to article 3 (Van Cauwenberghe), where he had actually come across the number. However, this article is still not the source of the ten percent figure. The researchers here refer to article 4 (Thompson).

This leads us to Richard Thompson, described as one of the leading researchers in the field of plastic debris in the oceans who has written articles in reputable publications. Article 4, however, is a contribution to a conference and not a scientifically quality-controlled article. Nevertheless, it has been quoted in plenty of links.

Regrets

Thompson, a professor at Plymouth University in England, provides no reference for the claim of ten percent of plastic refuse ending up in the oceans. So it is not identical to saying that ten percent of all the plastic produced globally ends up in the seas, which many have quoted him as saying. So the ten percentage share has taken on a different significance along the way. In any case, Thompson’s number is erroneous.

“– It was from a respected source, it seemed credible and I believed it as did others,” he writes in an e-mail to forskning.no. But he doesn’t answer the question of why he neglected to investigate the reference which the number comes from.

Thompson writes that he relied on grey literature, in other words, information from the authorities, organisations or academics who have not been peer reviewed through formal scientific publications. Typically, this could be a report, a work note or a presentation.

“On further digging there is no substance to them – they were guesses and I should not have used them. I have not used the quote again,” he writes.

Researchers’ responsibility to check the numbers

“I dislike that researchers use numbers which don’t hold up,” says Inger Lise Nerland.

“It’s our responsibility as scientists to be critical and always check the original source,” asserts Nerlund, who is doing doctoral degree research at the Norwegian Institute for Water Research (NIVA).

Nerland has also pondered the figure ten percent. When she and a colleague were working on a report about plastics in the ocean commissioned by the Norwegian Environment Agency, she only planned on using the number in the preface. She had heard scientists mention this ten percent at conferences and had used it herself in lectures when she was starting out as a doctoral student and, as she puts it, “a little less critical”.

But Nerland also had to give up the hunt. She searched for the number and failed to find it in any scientific publications. It appeared on all sorts of web pages, with references to the environmental organisation Greenpeace and a UN report. But in the said reports she couldn’t find the number.

“I was irritated. When we found there was no basis for it, we stopped using the number,” says Nerland.

Environmental research is vulnerable

Inger Lise Nerland thinks that environmental research is especially vulnerable to the spreading of errors, which nearly get established as truths. It’s a touchy, politicised field, with powerful interests involved.

A concrete figure about pollution can bolster arguments and be spread far and wide.

“A person might be tempted to get rather tabloid. In an introduction to a paper it looks very convincing, that we have a major problem here,” she says.

The demands from media, interest groups and politicians are huge. Everyone wants a forceful answer but scientists can only provide trickling amounts of information. The oceans are vast and the pollution of micro-plastics, tiny pieces or fibres of plastic, represent a rather new field of research.

Stopping pollution

“It’s boring to talk about uncertainty. And there’s a lot of pressure on researchers to find the numbers. But there is still much uncertainty regarding the little we know about plastic in the seas. It’s vital for us to make this clear,” says Nerland.

Do you ever get tempted to exaggerate?

“Pretty much the opposite. Maybe I’m particularly vigilant because I’m a fledgling researcher. I dread the thought of disseminating mistakes.”

“It’s clearly easy to get a little sloppy. But my impression is that most of us are adept at catching mistakes,” says the researcher.

Nerland does not know who arrived at the ten percent figure and spread it around in scientific circles.

“It must have been someone who isn’t objective. I think it could have been an interest group which is fighting the pollution.”

Impacting politics

The consequences of misinformation can be great, asserts Kevin Thomas, a research manager at NIVA who acts as Nerland’s advisor.

“It might be that we do research in the wrong places. It can lead to policies and environmental initiatives that don’t work. No mitigation of the problem will be seen if decisions are made on the wrong foundations,” says Thomas.

He thinks it insufficient to surmise that plastic pollution is a problem. It’s essential to know how big a problem it is.

“It’s deceptive for researchers to quote figures which they don’t know the source of. This is a bad way of doing things.”

Thomas, who has researched water pollution for years, does not have the impression that this is a common problem.

“I rarely see professional scientists using numbers without solid references,” he says.

Bottom of the sea

That said, there are other numbers in this field of research that have dubious or unidentified sources. One such is the claim by some that 70 percent of all the plastic debris in the oceans sinks to the seabed. This is hard to calculate, as scientists only find some of this debris and they don’t know how much was floating in the ocean to start with. There is a sizeable gap between the amounts of plastic scientists think is spreading to the seas and the amounts they find. They are constantly discussing what happens to the plastic.

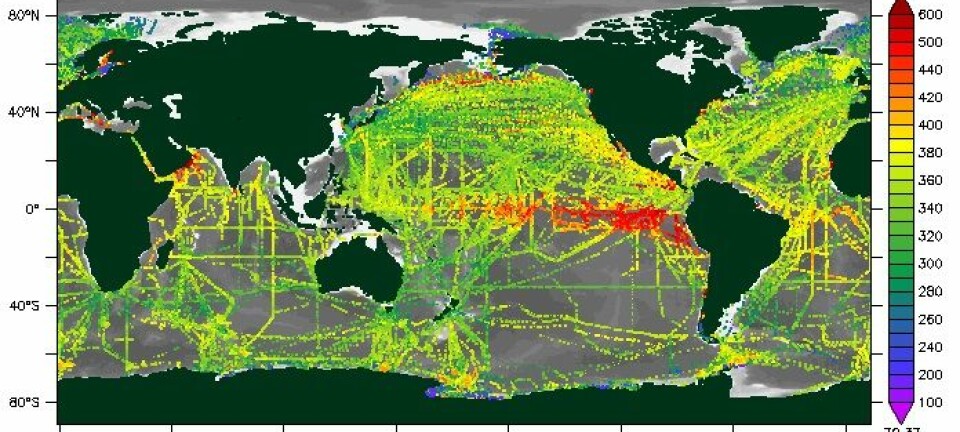

They have tried to chart the plastic floating around in the oceans, and that is hard enough. The seabed is all the tougher to monitor and control. Scientists do find plastic on the seabed in many places but they lack a general overview.

Referring to one another

We search for the basis of the 70-percent figure in published research. Once again, reports refer to one another without divulging where the empirical data comes from.

Norwegian governmental authorities have also used the figure. A report by the Norwegian Environment Agency claims that 70 percent of the plastic sinks, 15 percent floats and 15 percent gets stays in the shore zone. The report quotes the Ospar Commission, which is designated with the protection of the Northeast Atlantic on behalf of authorities in European countries.

The Ospar report, however, refers to Ocean Conservancy, an interest group working for trash-free and pollution-free seas which lobbies the US authorities. But when we contact them they cannot find the number in their report.

So, we failed to get to the bottom of the problem.

--------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- UNEP/Convention on Biological Diversity: Background document on the preparation of practical guidance on preventing and mitigating the significant adverse impacts of marine debris on marine and coastal biodiversity. Expert workshop, Baltimore, USA.

- Stephanie L. Wright, Richard C. Thompson og Tamara S. Galloway: The physical impacts of microplastic on marine organisms: a review. Environmental Pollution 178, 2013.

- ET&C Perspectives: Plastics in the marine environment. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, vol. 33, nr 1, januar 2014.

- Lisbeth Van Cauwenberghe m.fl: Assessment of marine debris on the Belgian Continental Shelf. Marine Pollution Bulletin 73, 2013.

- Richard C. Thompson: Plastic debris in the marine environment: consequences and solutions. I: Jochen C. Krause m.fl. (red.): Marine Nature Conservation in Europe. Proceedings of the symposium. Stralsund, Tyskland 12.–18. mai 2006. Federal Agency for Natur

- The Ocean Concervancy: 2004 International Coastal Cleanup Data Report. (link to website)

External links

- Inger Lise Nerland's profile

- OSPAR (2009): Marine litter in the North-East Atlantic Region: Assessment and priorities for response. London, United Kingdom.