Complicated climate communication

Impact scenarios of climate change on Norwegian ecosystems are indefinite and convoluted, making dissemination to the general public difficult. How can scientists express themselves clearly and precisely?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Seabirds are having problems along the Norwegian coast. Chicks are dying. The Atlantic puffin, with its distinct features, is readily cited as an example even though other species are more endangered in some areas.

Scientists who conduct research on the ocean, fish and seabirds attempt to explain the links between climate changes and the ecosystem. But an array of factors has impacts on birds high up in the food chain.

When the research is complicated and includes uncertainties, how short and apt can scientists be? Is it best for them to pack their statements in with reservations, with ample use of the words “can” and “perhaps”, or can they grant themselves a little leeway for speculations?

Researchers disagree about their roles and what they can allow themselves to say.

Difficult contexts

Dag O. Hessen, a professor of biology at the University of Oslo, has previously commented on the plunge in bird stocks and now regrets his own phrasing.

“I said that what is happening now is undoubtedly linked to climate changes. That lacked nuance, and I have to shoulder responsibility for it.”

“Causalities are hard to chart. Some will say that temperature changes in the ocean comprise the main reason for decreases in seabird populations. Others would just list this as one of many contributing factors,” says Hessen.

“Actually any given statement should be clarified with mention of uncertainties. But as scientists we are attacked for making excessive reservations, so now and then we get tempted to skip padding everything with a ‘maybe’.”

Uncertainty can be seen as boring. Hessen’s point is that researchers occasionally fall for the temptation of expressing more than they fully know.

“We should be able to say that something is probable, but be cautious about saying something is certain. Sometimes the difference is very subtle. Most researchers have probably stretched their conclusions a little too far at one time or another.”

Commitments can have an influence

The science and math used in climate research is studded with perplexing facts and a host of complex variables – but it also a political issue.

Researchers from certain fields are constantly being attacked for being steered by their political convictions.

“The goal of research is objectivity but I think contemporary researchers are influenced by their own principles. This is probably why we have different favourite explanations,” says Hessen.

Climatologists not more political than others

Helge Drange, a professor at the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research in Bergen, does not have the impression that climatologists are more politically oriented than other researchers.

“I think the main point here is how others perceive the credibility of the research. Losing credibility is the worst that can happen. If people think research is activism, we’re goners.”

“This doesn’t mean you have to sit in your office staring at the floor. It’s at least as worrisome if researchers fail to pass on their knowledge, if no one dares to utter a word.”

Dare to have an opinion

Hessen thinks that in such fundamental issues as global warming and climate change, scientists must dare to have opinions.

“Out of anxiety for not moderating themselves enough, some don’t dare say a word. Who should have more competence to judge than those who have actually researched the subject?”

Can researchers be activists and still express themselves as professionals?

“There’s a big difference between being an activist and being a researcher. On the other hand there are lots of researchers who complain that only organisations make statements about the climate. In that case they need to have the courage to have an opinion. But we should never be agitators,” says Hessen.

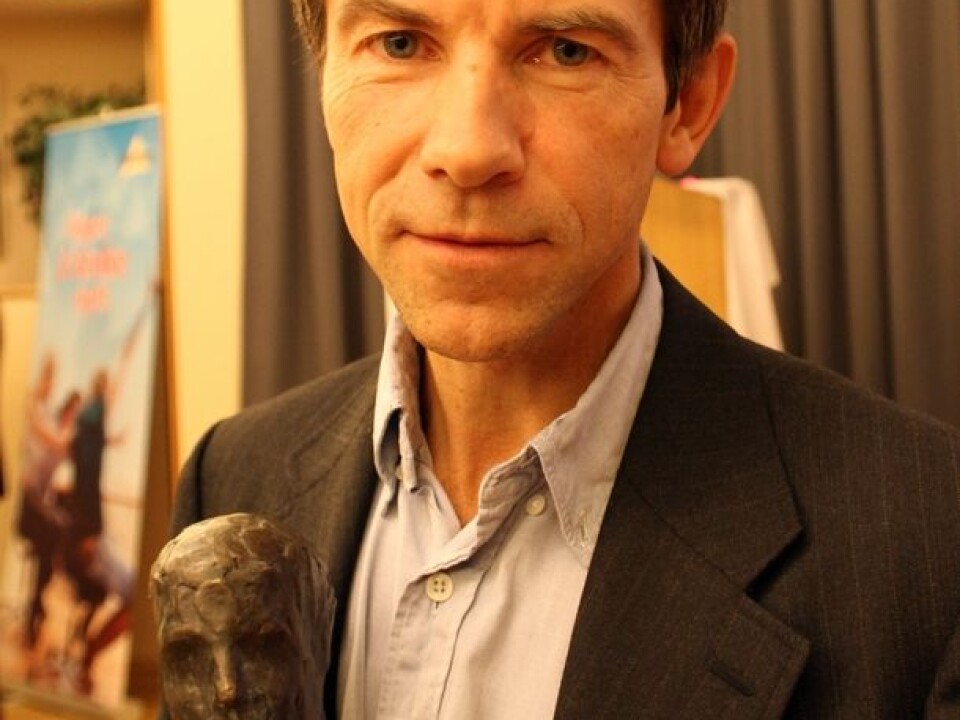

Paddling to the North Pole

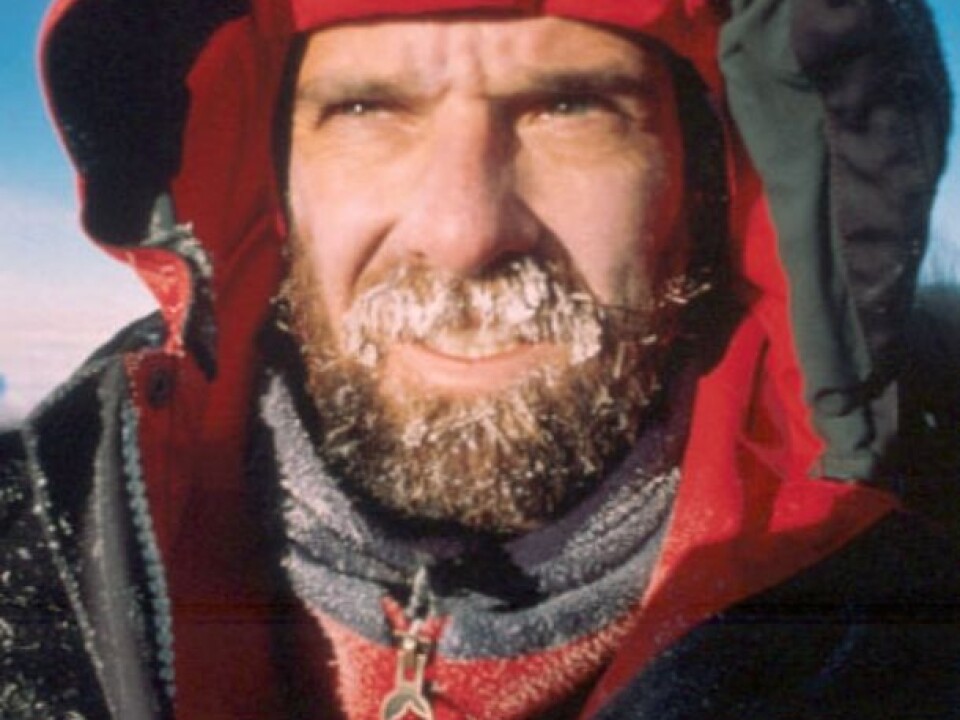

Jan-Gunnar Winther, director of the Norwegian Polar Institute, caught a lot of flak from other scientists for planning a kayak voyage to the North Pole in 2010 to get the idea across that the ice is melting fast. This was because he would be using public funds for a voyage that didn’t involve research and because he started out at a time of year where there is always less ice at the Pole.

But he rejects accusations of activism.

“I planned to disseminate research during the voyage. We talk about this a lot at the Institute – our credibility depends on accurate and factual information. That said, I think untraditional ways of spreading knowledge are important,” says Winther.

Faced with the criticism, he dropped the voyage.

“I didn’t want this to become a problem for the credibility of the Institute.”

Can scientists speculate?

When researchers express themselves about the impact of climate changes on nature and the ecosystems, they often stray a little outside their field.

Dag O. Hessen thinks that it would be suffocating if scientists were only allowed to express things within their own, narrow field of expertise.

He has not researched seabirds, but he does conduct research on marine ecosystems and can base his position on the research of others.

He thinks researchers have to dare to arrive at conclusions.

“But when we interpret things far outside our knowledge, we risk abusing our titles as professors.”

——————

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling