An article from University of Oslo

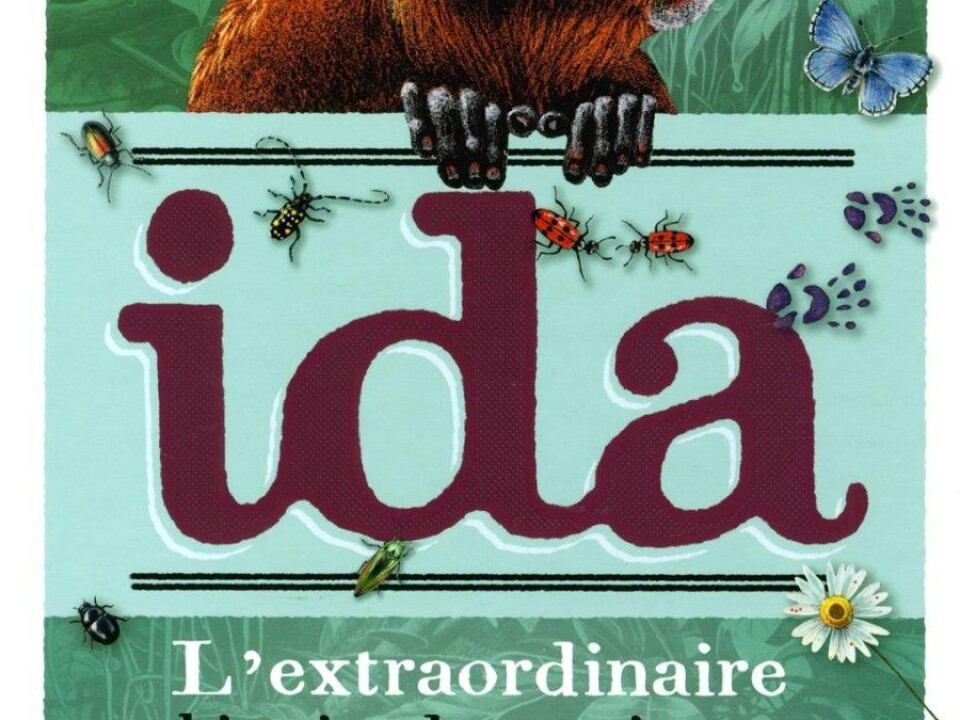

The fossil Ida – five years on

It’s been five years since the news of the fossil Ida was made public. What are the researcher’s thoughts about the media circus he initiated back then? And how did he deal with the anger he released in academic circles?

Let us first return to the morning of May 19th, 2009:

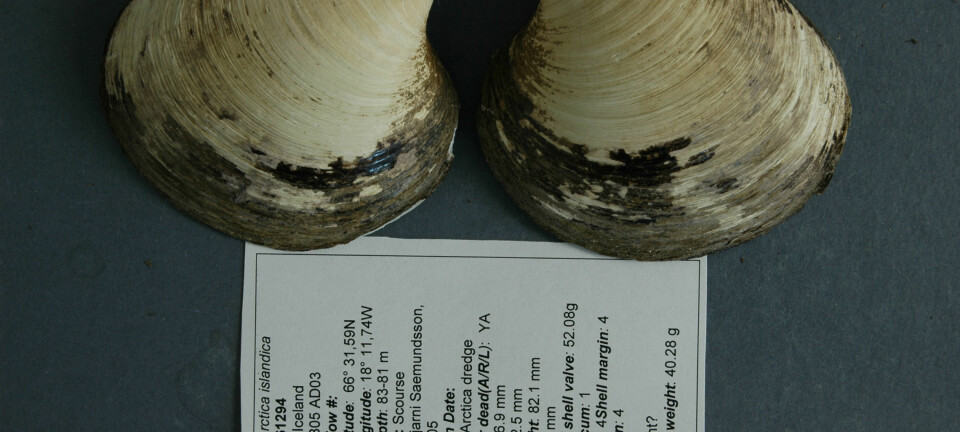

Associate professor Jørn Hurum of the Natural History Museum at the University of Oslo arrives at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. A press conference is about to be held, about the find of a 58 centimetre long, 47 million years old fossil. It is the most complete primate fossil ever found.

Jens L. Franzen, first author of the scientific article about the fossil, had suggested that the fossil should be named after Hurum’s five and a half year old daughter. The fossil died as it was teething, and Hurum’s daughter was also teething at that time.

40 international TV channels

The preceding day, Hurum and the other palaeontologists in the “Dream Team” behind the article describing Ida had visited the scene of the press conference. But as Hurum and his wife, the UiO scientist Merethe Frøyland, approach the museum the morning of the press conference, they think that there has been an accident. There are 40 cars with satellite antennae outside. A multitude of cables run into the building.

“I knew we had a great fossil and a good story to tell. And yes, I was certainly aware that there would be some media attention. Yet I have to admit that that day’s events still seem slightly absurd,” Hurum recalls.

BBC broadcasted the press conference live. 40 international TV channels were present. Google changed their logo for the day.

Many were angered

Reactions were immediate: "This is a media circus.", "Ida’s importance is exaggerated.", "The marketing is misleading."

The main impact was probably that John G. Fleagle, an international palaeontologist guru and the writer of some of Hurum’s textbooks, disagreed with the scientists’ conclusion.

While they claimed that Ida represented a transitional form with anatomical features characterizing monkeys, and also apes including humans, Fleagle thought they were wrong.

This wasn’t a monkey or an ape, but a lemur, he claimed.

A beautiful fossil, without a doubt, but in no way scientifically revolutionary. And, perhaps above all, the fossil couldn’t shed any light on human evolution.

In Norway, five professors of biology, some of them Hurum’s colleagues at the University of Oslo, also lashed out against him, stating that “Ida is oversold”.

The focal point of their criticism was that the fossil was promoted as “the link”, a phrase uncomfortably close to “The missing link”, at the press conference, online, in the documentary show andin the accompanying book The Link by British science writer Colin Tudge. The professors felt it was misleading.

The phrase "missing link" was coined in the 19th century, when claims were made that science missed the link between humans and other organisms. In modern evolutionary biology this link is thoroughly documented, so the phrase no longer has any scientific value, they claimed.

"Simplifying is crucial"

In the eye of the storm, Hurum managed to remain resilient. Although he admits that, for a while, the constantly ringing telephone was exhausting.

He did, however, have the full support of both the Natural History Museum and the University of Oslo.

“At the height of the controversy I was invited for lunch by the rector and the university director. The support I got from them meant a lot to me,” he says.

So, don’t the critics have a point when claiming that it can hurt science’s credibility if the gap between science and outreach gets too wide?

“Not at all. Had there been fifty palaeontologists in Norway occupying as much public space as I do, they might have had a point. But it can hardly be claimed that there is too much scientific outreach. If you want to connect with people, simplifying is crucial. If you include each and every single footnote, your outreach is unmoving,” Hurum says.

"At the time, a professor told me that I ‘should stop vulgarising my research’, and what impresses people, is what ‘they don’t understand’. With a stance on outreach like that, you don’t get very far,” he adds.

What about the title of the book: "The Link". Do you understand that people were provoked?

“I rather like the title myself. Having held numerous popular presentations about evolution, I can testify that the most recurring question and one of the first to be asked, is 'Have you found the missing link yet?' The phrase is commonplace in the real world. Of course it isn’t a scientific term. But we thought it was fun to play with words.”

“Even though lots of people disagreed with our conclusions, they could not pin any scientific errors on us”, Hurum emphasises.

The anger abates

In 2010, John G. Fleagle wrote an essay in a more conciliatory tone.

He analyses the reactions to the launching of Ida, and raises the question: “Why were we really so angered?” In the essay, Fleagle reaffirms his view that Ida does not add much to our

understanding of human evolution. Although he finds The Link a good read, he writes that the book never explains why Ida is supposed to be the most important fossil ever found.

What made them so mad?

Jørn Hurum confides that he has spent some time over the past five years wondering why some people were so outraged with him.

“After Fleagle’s essay were published, the worst was over. It was good to see the Number One in the field write so balanced about it.”

In the fall of 2009, Hurum received a visit from the Danish professor Peter C. Kjærgaard, who had analysed the debate surrounding Ida.

He made some things fall into place for Hurum.

“Ida was by far the biggest news in the Darwin Year 2009. Many people had planned books and big meetings this year. Kjærgaard thought that we were seen to be stealing the limelight from others.”

“The Darwin Year hadn’t really mattered that much to us, we had originally planned to publish a year earlier. When Kjærgaard mentioned this, several things fell into place for me. Up until that point, I had really never understood the passion behind the anger,” Hurum states.

Was Jørn Hurum wrong?

When the researchers started studying Ida, their hypothesis was that she was related to lemurs. One year later, they thought she was closer to apes and monkeys.

Today, the pendulum has swung back, and the lemur hypothesis is now the most favored one. But there are still some, also inside the “Dream Team”, that would place her on the ape/monkey branch.

Hurum is still on the monkey side.

“I find the anatomical arguments more convincing for this.”

Statistically, however, most place her on the lemur side of the divide.

"Even the distinction between lemurs and monkeys has changed because of Ida. As she has features from both sides, the basic anatomical definitions on primates has had to change," Hurum explains.

The future

No one knows what the future holds for Ida.

“This is an ongoing discussion. Until there are more good fossils as old as her, or older, she is still the most complete primate fossil ever seen. She is thus an iconic object representing our early relatives 47 million years ago.”

Hurum points out that science is driven by disagreements

“When everybody agrees, we're talking about religion, says Hurum,

He concludes with a quote from the Ida debate, published in Nature: “Science moves forward funeral by funeral … almost no one ever changes their mind.”

------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no