When a flood of immigrant workers becomes a trickle

When Poland joined the EU in 2004, unemployment was at 20 per cent, and a flood of workers left the country for higher wage lands such as Norway. Now the tide has turned, and Norway faces labour shortages as Poles stay home.

Norwegians have taken Polish workers for granted, and even seen them as a problem.

A May report by Fafo, a Norwegian non-profit research foundation that looks at labour issues, shows that 44 per cent of respondents believe that labour immigrants are pushing less well-qualified Norwegian workers out of the labour market.

Half of respondents agreed that labour immigration from Eastern Europe has depressed Norwegian wages.

But recent numbers show that emigration from Eastern Europe is roughly equal to immigration from the region. The net number of immigrants from Poland to Norway was 28 people last year.

At the same time, the Norwegian construction industry is facing severe labour shortages. This is the Norwegian industry that has employed the most Polish labour immigrants.

Unemployment nearing record lows

The Federation of Norwegian Construction Industries (BNL) reported earlier this year that unemployment rates in the sector are falling and are lower than they have been for many years.

The labour market is tightening, and unemployment is low throughout Europe, especially in the construction industry, where there is a great shortage of qualified labour.

Iwona Kilanowska, an adviser at BNL who is from Poland, believes Norwegian industries should be a little worried about this trend.

“Companies and organizations still talk as if there is endless access to labour immigrants. I don't see any signs of specific activities or campaigns in the industry to attract people from abroad — or keep them,” she said.

Mass emigration

Kilanowska is among the 2.5 million Poles who left when Poland became part of the EU in 2004.

Through the EEA agreement, Norway is part of the Union's internal market and many from Eastern Europe came to Norway, especially from Poland.

“No one imagined how massive this immigration was going to be,” said Fafo researcher Rolf Andersen at a Fafo conference on 15 May this year.

In 2018, roughly 185,000 people from Eastern Europe were employed in Norway. Among these, 130,000 resided in Norway, while another 55,000 travelled back and forth between the two countries, according to figures from Statistics Norway (SSB).

The largest group came from Poland.

A reverse in trends

The tide has now turned.

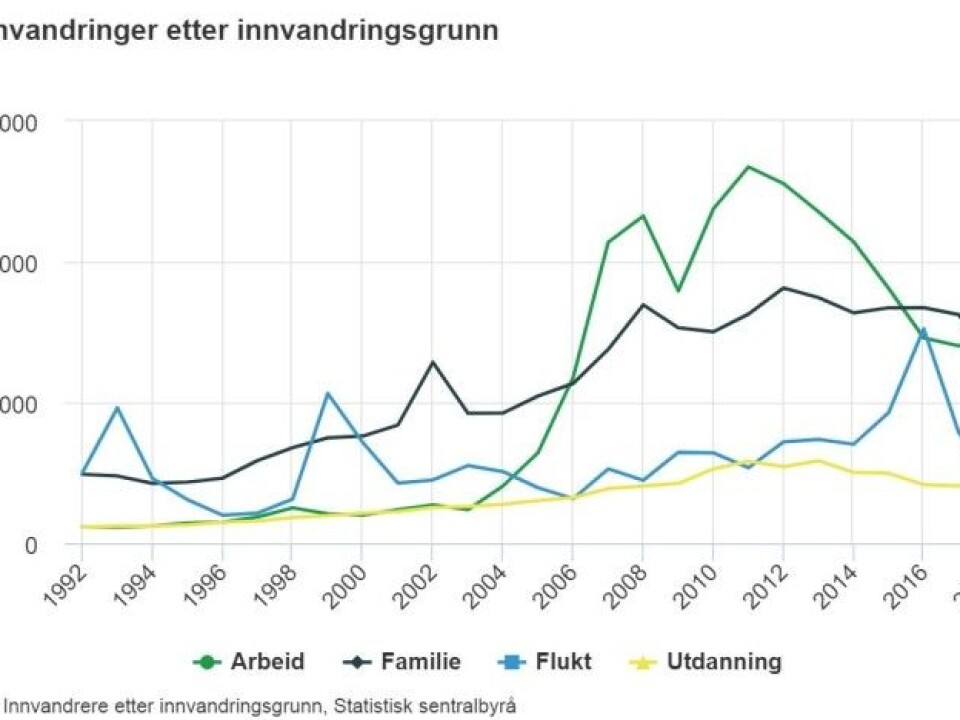

Figures from Statistics Norway show that labour immigration has dropped sharply, Almost 27,000 immigrants (excluding other Nordic countries) came to Norway in 2011, which was the peak year. Immigration has fallen every year since then.

The main reason why Kilanowska and many other Poles left their country when Poland joined the EU was that unemployment at that time was a sky-high 20 per cent.

Today, unemployment in the country is historically low, around 5.5 per cent. By comparison, unemployment in Norway was 3.8 per cent at the end of April this year.

Poland has experienced increased economic growth since the country joined the EU, and wages have also increased. In addition, the current government has provided fairly generous child benefits to families for the first time.

What goes around comes around

Now, the construction industry in Poland is struggling to employ skilled labourers, while wages in the sector have risen significantly compared to other industries, Kilanowska says.

Polish construction companies have now had to attract immigrant labourers, particularly from the Ukraine and Asia.

Poles are consequently having the same discussions about immigrant labourers and working conditions that took place when Eastern Europeans first came to work in Norway, Kilanowska said.

Many immigrants who leave their countries for work can make good money, but their legal rights are weak and their employment conditions can be poor, she said.

Earnings up in Poland

Polish professionals are now well paid and their quality of life is good, so they don’t have to leave their family to find work outside of the country, Kilanowska says. As a result, fewer are emigrating, she said.

Nearly 90 percent of Polish respondents to a 2018 survey said they are not interested in seeking work abroad. In 2014, that figure was 79 per cent.

The Polish polling agency Work Service surveyed a representative sample of 593 Poles. Eighteen per cent of respondents said they did not want to leave Poland for work abroad because the cultural differences are too great.

Twelve per cent said they did not want to work outside of the country because they believe that Poles are poorly treated abroad.

-----------------------