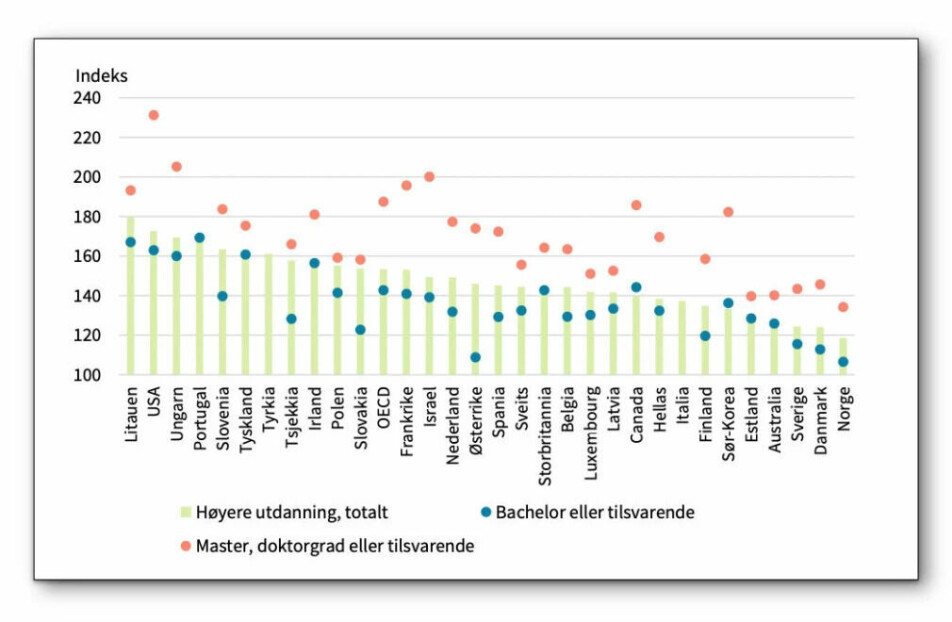

Norway is the country where you get the least return in terms of income from getting a higher education

People with a higher education level from university or college in Norway earn 19 per cent more than individuals with an upper secondary school diploma.

If you ‘only’ pursue a bachelor's degree, you’ll have to settle for a seven percent higher salary than someone who ends their formal education after upper secondary school.

With a master's degree or doctorate, your average income will be 34 per cent higher than the income of a person with a secondary education diploma.

The average salary increase you gain by pursuing higher education in Norway, compared to just finishing upper secondary school, is 19 per cent.

These figures appear in the OECD's ‘Education at a Glance 2021’ report and in the ‘Indicator Report 2021’ from the Research Council of Norway.

Norway is also one of nearly a third of the countries in the OECD report that do not charge any tuition fees to national students enrolled in bachelor’s programmes.

Biggest difference in USA and Germany

In other countries, the average increase in earnings beyond upper secondary school is 43 per cent for a bachelor's degree and 87 per cent for a master's degree or doctorate.

The greatest difference linked to education and income is found in countries including the USA, Germany, Turkey and Chile.

The general world trend is that pursuing studies at the bachelor's, master's or doctorate level has a significant payoff in terms of higher wages.

In the most developed countries of the world (OECD countries), however, the earnings gap between people with less and more education has decreased in the last ten years. Only in Hungary and Turkey has the difference grown.

Larger wealth difference

Economic inequality is not just about income. It is also about wealth.

Both in Norway and other countries, the economic differences are generally much greater if we look at wealth than if we look at income.

People in Norway with additional education have distinctly higher wealth than people with a more limited education. Here, the difference in Norway is about the same as the average in Europe.

Norwegians want small differences

The prospect of a better salary is one of several reasons for furthering one’s education beyond upper secondary school.

Much of the explanation for the fact that people with more education earn relatively little extra in Norway may be because people with less education earn relatively well in the country. We like to talk about having a ‘compressed wage structure,’ and Norway’s wage structure may be the most compressed in the world.

Put simply: Norway has small wage differences compared to other countries, and that is probably how a large proportion of the population wants it to be.

In the Norsk Monitor (Ipsos) social research survey for 2021 and 2022, 58 per cent of the respondents reported that the wage differences in Norway are too high, according to NTB, the Norwegian News Agency. This is the highest level measured since the question started to be asked in 1985.

Found a high return on longer schooling instead

Kjell Gunnar Salvanes is a professor at NHH Norwegian School of Economics in Bergen. In a study he carried out with colleagues Manudeep Bhuller and Magne Mogstad, they found quite different results from what appears in the OECD's figures.

“We see that on the contrary, the return on furthering one’s education in Norway can be very good,” says Salvanes.

“Our starting point was to look at the return when you compare lifetime income for the different education groups and not just compare them for one somewhat random year.”

Interest at 11 per cent

The three social economists decided to calculate how high the internal rate of return is from pursuing higher education in Norway, applying economic theory based on the investment of capital.

Simply put, the internal rate of return calculates how high a monetary return you can expect in the future, if you invest in higher education.

“We found an internal rate of return of 11 per cent for pursuing higher education in Norway,” Salvanes says.

“That isn’t a bad return. This finding indicates that pursuing higher education in Norway can be very profitable, too,” he says.

“The return on higher education in Norway isn’t as high as in the USA or in other countries with large wage differences. But it’s still high.”

Different calculation method

Salvanes and his colleagues arrived at a different result than the OECD because they used a different method for their calculations.

“The OECD figures provide us with a snapshot,” says Salvanes.

“We’ve tried to calculate what your increased lifetime income will be if you study at a university or college.”

Salvanes adds that additional education can also have other benefits. Among other things, it can serve as insurance against losing your job.

“This finding is part of a new research project we’re working on now,” he says.

“You can also reap non-monetary benefits from education, such as better health and perhaps more flexibility at work.”

Other advantages mentioned in surveys by people who pursue higher education is that they find more challenging and interesting jobs. Perhaps they also enjoy more interesting colleagues at work.

Big differences between education programmes

Salvanes says that researchers Lars J. Kirkebøen (SSB), Edwin Leuven (UiO) and Magne Mogstad (UiO) have done another study which is also interesting in this context.

He notes that they found major differences between various bachelor's and master's programmes in Norway.

“So this means that your choice of higher education programme is not inconsequential, if your goal is to be paid a high salary,” says Salvanes.

References:

OECD: Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021.

Research Council of Norway: Indicator report 2021. Report, 2022. (in Norwegian)

Manudeep Bhuller, Kjell G. Salvanes et.al.: Life-Cycle Earnings, Education Premiums, and Internal Rates of Return. Journal of Labor Economics, 2017. (Summary)

Lars J. Kirkeboen et.al.: Field of Study, Earnings, and Self-Selection. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2016.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------