Which inequalities do people think are okay? Norway and China come out at opposite ends

Is a little inequality ok if it's a result of some people working harder than others? Researchers did a behavioral experiment and found that the answer to this depends on which country you live in.

Is everyone against all inequality? Or do people find some types of inequality okay?

In a major new study, researchers at NHH - the Norwegian School of Economics have investigated how people in different countries perceive inequality.

The survey was conducted in 2018. More than 60 000 people from 60 countries participated in the study.

The main results are now ready and will soon be published in an international scientific journal.

The research shows that Norwegians abhor inequality caused by luck. At the same time, they are more inclined to reward high achievement than we might think.

The idea that those who perform better deserve more is a common feature of several rich Western countries, the researchers found.

Survey and experiment

The researchers teamed up with the analysis agency Gallup World Poll to conduct the global survey. It consisted of both a behavioural experiment and a survey.

The participants answered questions on topics including what kind of attitudes they have towards redistribution.

In the behavioural experiment, the participants had to choose whether they wanted to redistribute money.

“They were put in a situation where they had to make a real distribution choice as a third party,” says Professor Bertil Tungodden.

He collaborated with Ingvild Almås, Alexander W. Cappelen and Erik Ø. Sørensen to carry out the study, who are researchers at the NHH FAIR Centre for Experimental Research on Fairness.

Made an executive decision

In the experiment, two participants performed a job for the researchers and were to receive a reward. One of them then received all the money, six dollars. The other participant got nothing.

A third person had to choose whether to intervene in the distribution of the money.

Should the third person refrain from intervening? Should the money be shared equally, or should the person who received no money get a smaller share of the total?

In one group, it was made clear to the third party that luck was the reason one person received all the money.

The third party in another group learned that whoever received the money had performed best on the task.

For a third group, redistributing was associated with a cost. For example, if the third party opted to split the amount equally, two dollars were removed from the pot.

Inequality between 1 and 0

The results showed that there were big differences in how people from different countries chose to allocate the money.

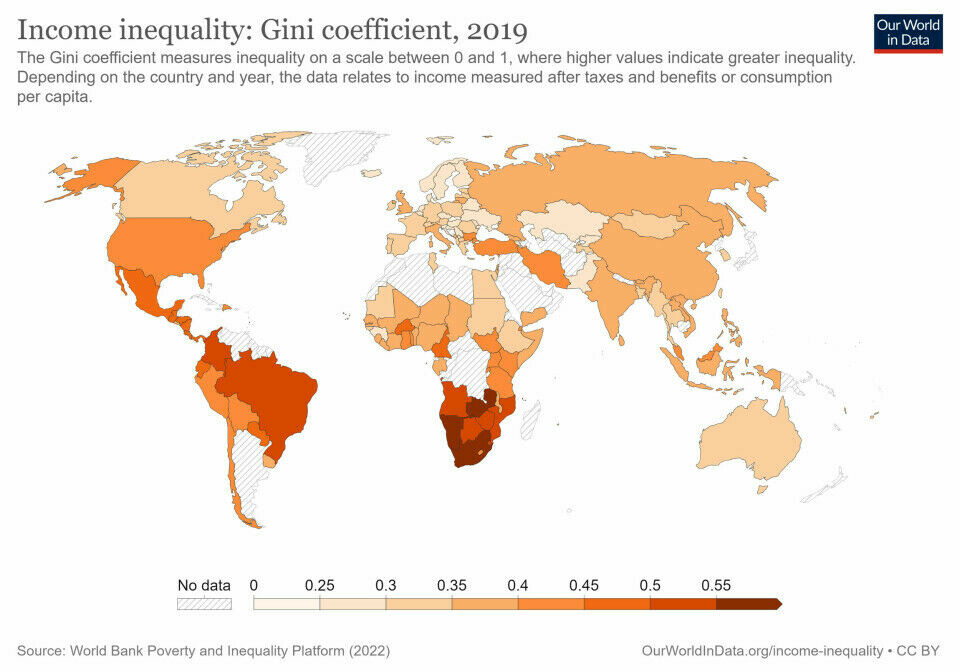

Inequality is often measured using an indicator called Gini. If Gini is 1, it means that one person has all the income in the country. This is the maximum inequality. If Gini is 0, it means that everyone has exactly the same amount of income.

In reality, a country's Gini lies somewhere in between 1 and 0. Norway has very low inequality, while South Africa, for example, has a very high degree of inequality.

“A Gini of 0.6 is sky-high inequality in reality,” Tungodden says.

Different value base

The researchers looked at how much equality and inequality people chose to create in the experiment.

They used the same Gini measure and looked at the Gini value each participant created with their choice. They then calculated the average for each country based on all three groups.

“The first thing you understand is that there are big differences in the value base of different countries,” Tungodden says.

“Even when we put people in the same situation and control their perception of the source of inequality and the cost of redistribution, we see large differences in distribution choices between countries,” he says.

Mirrors the real world

The experiment seemed to mirror the inequality we see in the real world. In South Africa, for example, little redistribution took place in the experiment. This is in line with the high level of inequality in the country.

“Norway was actually the country exercising the least inequality in the experiment, which very much mirrors the country’s actual situation. It's quite striking,” Tungodden says.

The researchers cannot say what happens first: whether a lot of inequality in a country means that people accept it more or if a high level of acceptance of inequality helps to maintain inequality in the country.

Unfair according to Norway

China, which is ruled by the Communist Party, was the country in the experiment where the most inequality was exercised.

“Being part of a communist system seems to have contributed to people being more accepting of inequality. We can only speculate why,” Tungodden says.

The researchers also looked at whether inequalities were due to luck or performance.

People in Norway did not want one person to get all the money when it was just due to luck. They most often chose to share.

“This shows that in Norway inequality that’s due to luck is not accepted. We just don't accept that. The entire welfare state is grounded in that basic belief,” Tungodden says.

China’s responses were at the other end of the scale. They interfered much less often and let one person have everything.

“In China, we observed that this form of inequality is accepted to a great extent. It’s incredibly interesting.”

Fine for one child to get more

Tungodden and Cappelen have collaborated with Ranveig Falch to follow up the difference between Norway and China in another study.

“Where does this difference come from? It’s a big and deep question that a lot of people are working on. We looked at it in one way with the experiment. Then we went back to China and Norway and did a survey,” Tungodden says.

The researchers imagined that attitudes are formed during childhood, when you begin to form a view of what’s fair and what isn’t.

They carried out new experiments where two children were to be rewarded for a task. An adult third party could choose to intervene in distributing the money.

“We created inequality among children all the way down to the age of five,” says Tungodden.

“What’s totally fascinating is that the study shows almost as much acceptance of inequality due to luck in Chinese five-year-olds as in the adult Chinese population.

“People’s views start on day one. In Norway, the acceptance of inequality among children is approximately zero.”

Get what’s deserved?

The researchers also looked at how people around the world view inequality if the reason is that one person did a better job.

Then the numbers changed dramatically.

“All over the world, we see a huge change in acceptance if inequality is due to performance,” Tungodden says.

Norwegians were also less eager to share equally when one person performed better than the other.

Less concerned with efficiency

In the third group, the researchers looked at how people chose to distribute the money if it cost something to do it.

People shared slightly less money when it cost them something than when they received the money due to luck. But cost had far less impact than if the participants were told that one person performed better.

The fact that redistribution entails costs and can be an obstacle to efficiency is something that economists are – and should be – concerned about, says Tungodden. But the researchers found that most people are primarily concerned with what feels fair.

Norway is not an egalitarian country

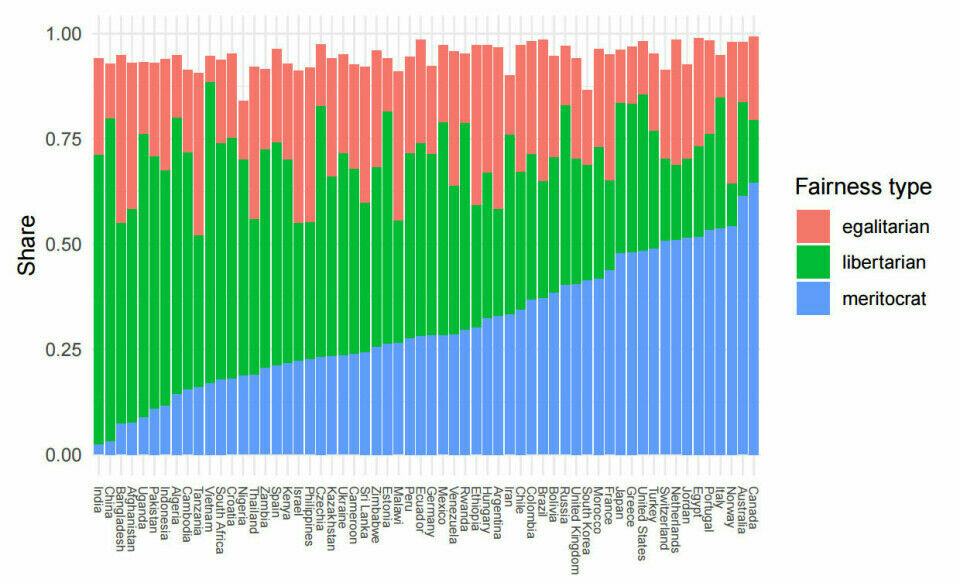

The researchers also looked at what proportion of the population can be said to have different attitudes, based on the experiments.

Egalitarians want as few differences as possible.

“The egalitarians don’t care about the source, they just dislike inequality in general,” Tungodden says.

Norway, for example, is seen as a super-egalitarian country in the USA, he says.

People who are meritocratic do not accept inequalities that are due to luck, but they accept inequality due to performance, Tungodden says.

The experiment suggests that Norwegians are more meritocratic than we might think.

“Norway isn’t an egalitarian country, it’s a meritocratic country,” says Tungodden.

“We see it in sports, for example. We’re obsessed with all our star athletes, and not many fans complain about what they earn.”

Reason less important

The researchers saw the same tendency to reward performance in several other rich Western countries, such as Canada and Australia.

Tungodden believes that meritocracy is a Western idea and not a global idea.

Libertarians, however, think it's okay for some people to get more than others, regardless of the reason. They don't really care if you receive money due to luck or because you performed well.

This view was most common in China and India, according to the experiment.

More research to come

“This is the first global study of this type that has gone deeply into how people think about inequality as measured through the choices people make,” Tungodden says.

The researchers found that people in different countries had differing views on what is fair and unfair.

They will explore the results further. They want to look more closely at whether religion can shape people’s view of inequality.

The term ‘luck’ can be interpreted differently in different countries, for example, says Tungodden. In some cultures there is no such thing as luck, and everything that happens has a meaning.

Negative consequences of inequality

In general, there appear to be many benefits to reducing economic inequality within a country.

Countries with greater economic inequality than others have more social problems, according to a previous forskning.no article (in Norwegian).

People in these countries have shorter life expectancy, more mental illness and there is more crime.

In a study from earlier this year, researchers found that earning less than one’s peers was linked to having more physical pain.

Inequality in Norway is increasing, according to a report commissioned by the Norwegian Directorate of Health earlier this year.

Low socio-economic status in Norway is linked to negative health outcomes both physically and psychologically. On average, people with high socioeconomic status live longer.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no