The richest Norwegians pay the least taxes

Researchers now see that income inequality in Norway is much greater than official figures have shown.

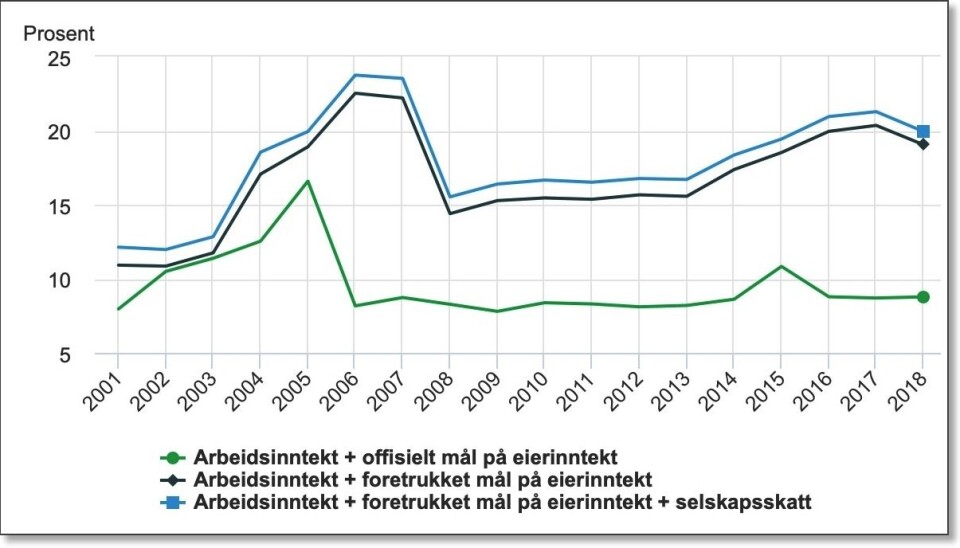

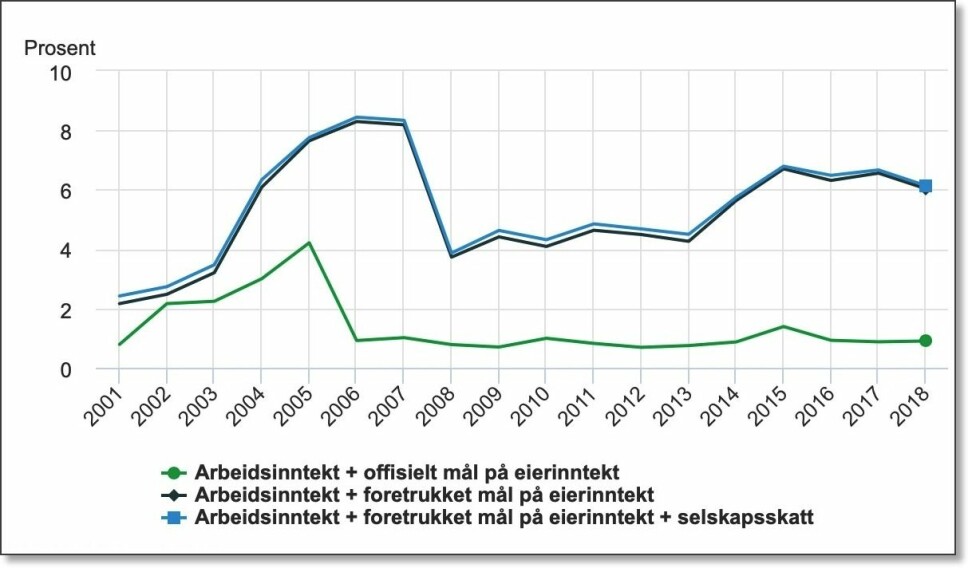

Norway’s richest 1 per cent have roughly 10 per cent of all income in the country — according to official statistics, at least.

“The real figure is 20 per cent, or twice as high,” says Statistics Norway researcher Rolf Aaberge to sciencenorway.no.

Norway’s super-rich — or the richest 0.01 per cent of the population— have about 6 per cent of country’s income.

A new Statistics Norway report that Aaberge has written with his colleagues Jørgen Heibø Modalsli and Ola Lotherington Vestad demonstrates how income inequality in Norway is much greater than what it appears from the official income statistics.

The main explanation for this is that the official statistics only include income reported on personal tax returns. A second reason is that company owners have clearly taken out smaller dividends after the country introduced a dividend tax in 2006.

The richest pay the least tax

The study behind the report makes it clear to researchers that Norway’s richest 1 per cent pay the least tax.

The richest in Norway only pay somewhere between 10 and 20 per cent tax on their real income.

If the richest had paid tax on their entire income, the tax revenue to the country and the municipalities would have increased by an estimate NOK 52 billion in 2018, Aaberge has calculated for sciencenorway.com. (This figure is in 2015 krones and is even higher when calculated using the value of today's krone.)

The statistics have been wrong

Following the introduction of a tax on dividends in 2006, the richest owners of limited companies have taken out significantly less in dividends from their companies.

This is clearly what has caused the income inequality that is described in official statistics to be measured as less than what it really is, the researchers have shown.

Norway’s official statistics are in accordance with international statistical standards determined by the UN, where the aim has been to achieve the best possible comparability across countries.

But this means that the official Norwegian statistics provide an incomplete description of how much of their income the richest 1 per cent pay in taxes.

“We have access to more data in Norway than in most other countries. We have data that show us accounting figures and lots of information about ownership for all Norwegian companies, among other things. We don’t have to settle for income reported on personal tax returns, as is the case in many other countries,” Aaberge said.

Twice as much in earnings in reality

Aaberge and his colleagues at Statistics Norway have found that almost all of the discrepency that is created by the UN's measurement method is due to the fact that the richest 1 per cent actually earn around twice as much as the figures from their tax returns show.

“For the other 99 per cent, the tax system seems to work progressively, with increasing taxes on increasing income,” Aaberge said.

If Norway is to be true to the ideal of paying tax according to ability, then the country’s tax system works as it is meant to for 99 out of 100 Norwegian taxpayers.

From 0 to 32 percent tax

The Statistics Norway's research department has some of the country's foremost researchers on economic inequality. These researchers have long been aware that there have been weaknesses in Statistics Norway's official statistics on income inequality. The issue is that the figures are primarily based on personal tax returns submitted by all taxpayers.

“So we started to investigate the kind of income that is not reported on personal tax returns,” says Aaberge.

The under-reporting of company owner income is related to the introduction of a dividend tax in 2006. With the exception of the year 2001, share dividends were tax-free in Norway before 2006. Before 2006, this meant that the majority of company profits were paid as dividends to owners. As a consequence, the reporting of income and the concomitant payment of taxes were far more accurate and equitable.

However, the introduction of the dividend tax in 2006 gave company owners a strong incentive to hold on to a large percentage of a company’s profits. This in turn has led to an incomplete description of both income inequality and the associated tax burden.

“The taxation of share dividends made it profitable for company owners to keep as much of the money in the business as possible, instead of paying it as dividends to owners. This is called tax adjustment,” Aaberge said.

Inequality fell like a stone

It is the richest, above all, who make a lot of money from owning companies.

So after 2006, when the very richest took out far less money from their companies in dividends, that resulted in less income being reported on their personal tax returns.

“This is apparently why economic inequality in Norway fell like a rock from 2005 to 2006,” says Aaberge.

Since then, it has continued to be significantly less than it was before 2006.

Have found more accurate numbers

The three Statistics Norway researchers, all of whom are experts on economic inequality, have now tried to come up with more accurate figures.

They have done new calculations that include company income that is not paid as dividends to owners. This, they believe, provides a more complete measure of income inequality than what the official statistics show.

The researchers found that the proportion of income that accrues to the richest in the years after 2006 has been between 71 per cent and 176 per cent higher than what appears on tax returns.

For the remaining 99 per cent of taxpayers, the retained capital in companies has only a small effect on income, the researchers found.

“The results paint a completely different picture of the income of the very richest,” Aaberge said. “By avoiding a dividend tax on the majority of their income, the richest have paid a significantly smaller share of their income in taxes than most other taxpayers do.”

Income inequality is significantly greater

By taking into account the retained income in companies, Statistics Norway's researchers have also shown that income inequality in Norway is much greater than what it appears to be in the official statistics.

“The official statistics have given us better information about the effect of tax-motivated adjustments than about the distribution of income the individuals have at their disposal,” Aaberge said.

It’s important to note that it is not just official statistics, but also a lot of research which take as their starting point the information from taxpayer-submitted returns.

But the purpose of these tax returns is to determine how much an individual should pay in taxes, not to provide the best possible figures for statistics and research. This is especially true when it comes to understanding just how wealthy the very richest are.

Taxes are rising - but not for the richest

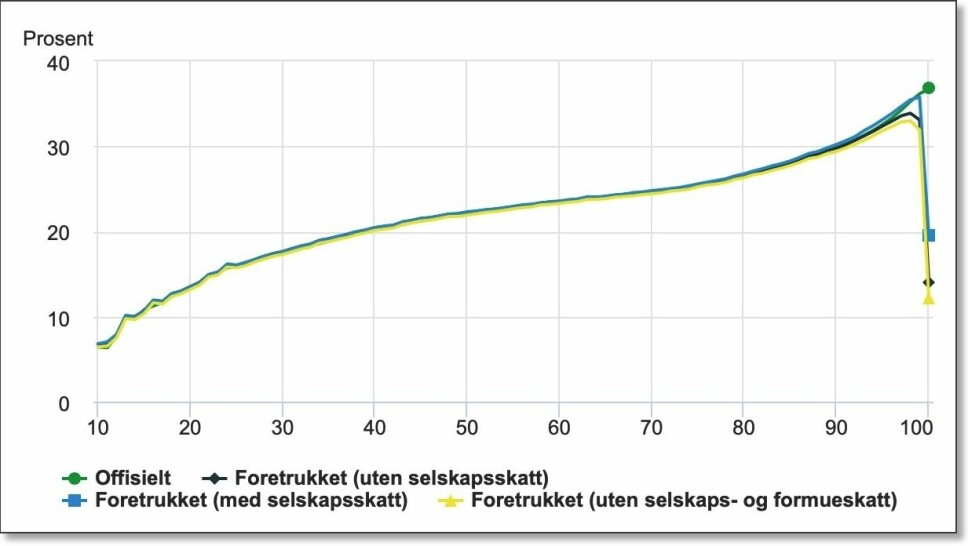

The researchers also calculated how much people with different incomes actually pay in income and wealth tax.

The figure below shows numbers from 2016. A person with a completely average income (50th percentile) paid 22 per cent in taxes that year. A person who belonged to the 99th percentile paid 35 per cent tax.

According to official statistics, the very richest in the country (100th percentile) paid 36 per cent tax on their income.

But when researchers also looked at accounting figures and ownership data, instead of just looking at income reported on personal tax returns, they were able to see how the tax rate for Norway’s very richest fell dramatically.

This new calculation showed that Norway’s richest only paid somewhere between 10 and 20 per cent tax on their real income.

Norway’s richest 1 per cent clearly pay less tax on every krone earned than most people, the researchers conclude.

Should tax be paid on retained income?

Some people will likely object that Aaberge, Modalsli and Vestad’s estimate of the tax burden paid by Norway’s richest has nothing to do with reality.

When a rich person leaves earned income in the company he or she owns, it’s possible to argue that it’s unreasonable for this person to pay income tax on that wealth.

“I have a bit of a hard time understanding that a person's income from a company should be treated differently than other people's income,” Aaberge says in response.

He notes that most wage earners have no choice when it comes to taxation. First they pay tax on their gross income, and then they can decide how much of their income after taxes is to be used for consumption and savings. If they spend this money, they pay an additional 20 to 25 per cent tax on the money in the form of various taxes on goods and services.

“Rich people can use their companies as piggy banks and also invest in assets that can be used for private consumption. As shown in an article from 2014 by Annette Alstadsæter and others, this is commonly what happened with small and medium-sized companies after the 2006 tax reform,” he said.

“The suggestion that this ‘saved’ tax is invested in new jobs is debatable,” Aaberge said.

“In addition to investing in assets that are of a more private nature, company owners can also buy shares in foreign companies and invest in new technologies to save on labour costs. But we need more research on this before we can say anything with more certainty,” he said.

Economic inequality is more than just income

This study specifically looked at income and income inequality.

But it’s important to keep in mind that numbers describing income inequality don’t provide a complete picture of economic inequality in Norway.

Large fortunes invested in homes and holiday homes are significantly more unequally distributed than income. This means that the economic difference between Norwegians is clearly greater than what appears from the figures for income inequality.

On the other hand, individuals with the lowest incomes and in the lowest tax bracket also benefit most from a number of public services, such as social security benefits through NAV, the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration. This helps reduce inequalities in Norwegian society, as has been shown in several studies from Statistics Norway.

Income that isn’t accessible?

Kristin Clemet is a former Minister of Education and Research and now the managing director of the liberal think tank Civita. She has repeatedly engaged in the debate on taxes and economic inequality.

Clemet thinks it is always good to do more research on economic inequality.

There is probably no reason to doubt the Statistics Norway numbers, she says. But at the same time she points out that the study raises questions that may be of interest for future research.

Clemet believes that, first of all, researchers should think about the validity of using the word “income” to include income that cannot be used.

She also questions whether the researchers have fully taken into account that income is taxed at 31.68 per cent before it can be spent.

“And have researchers thought about what would happen to the Norwegian economy and businesses if all this income was really used for consumption?,” she said.

Is Norway really more like the United States?

“It’s unclear to me whether this new assessment of inequality that the researchers used is more or less comparable to measurements of inequality in other countries, or to the measurements of inequality that we have for Norway before 2000. Does this change Norway's relative position as one of the countries in the world with the lowest income inequality?,” she asks.

“If these new figures are indeed the best and most comparable figures, meaning that Norway is actually more like the United States than Denmark, it raises many new questions and perspectives on the inequality debate,” Clemet points out.

“We have in fact believed that there is a link between relatively low income inequality and good results for many other parameters, such as trust,” she said.

“If Norway can be considered more similar to the United States when it comes to inequality, does that mean that societies with high inequality can also be very well-functioning and have very high levels of trust?” she said.

Finally, Clemet points out that the quality of life for the vast majority of Norwegians has improved since the turn of the millennium. She wonders if it then makes sense to use a measurement of inequality that is so largely driven by the few at the top.

Destructive to the Norwegian model of society

Kari Elisabeth Kaski, a politician in the Socialist Left Party (SV), has also become engaged by the new Statistics Norway study.

“This is earth-shattering when it comes to the debate on inequality,” she said to Dagbladet, a national newspaper.

“Most people have no idea how skewed income equality in Norway actually is,” she said.

Kaski believes that Norway’s entire social model is at risk when not every citizen pays taxes according to their ability. She wants the Norwegian Parliament to increase taxes on the rich as quickly as possible.

She also thinks the Statistics Norway report should play a role in Norway’s upcoming national elections in 2021.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Rolf Aaberge, Jørgen Heibø Modalsli and Ola Lotherington Vestad: “Ulikheten – betydelig større enn statistikken viser. (The difference - significantly greater than the statistics show)”, Statistics Norway Analysis 2020/13. The report (in Norwegian only).

Anette Alstadsæter et al.: “Are Closely Held Firms Tax Shelters?”, In Tax Policy and the Economy, Columbia Press, 2014.

Kalle Moene: “De ekstremt rike. Tøyler den skandinaviske modellen overklassen?

(The extremely rich. Does the Scandinavian model rein in the upper class?)”, Article in the national newspaper Dagens Næringsliv, 13 March 2015.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no