Why is Russia's economy doing so poorly?

The elites' power and desire for money slows down economic growth.

Jardar Østbø is a professor at the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies (IFS) and leads a project where researchers have looked more closely at the finances of Norway’s large non-democratic neighbour. His prognosis is simple.

“Russia has poor prospects for economic growth,” he says.

“In Russia, President Vladimir Putin doesn’t actually get up in the morning and know that he holds all power in the country,” Østbø said. “The Russian power system is based on three different power elites, popularly called ‘clans’.”

Østbø says these three clans decide what happens with the country's money and other resources. Putin must constantly ensure that the balance between them is maintained.

And this is where the researchers see that Russia's major economic problem lies.

The elites and the fragile balance of power between them stand in the way of both change and innovation.

The situation also retards the prospect of better living conditions for most Russians.

The strongest elite comes from the security services

In the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, it was the oligarchs, the people who had secured ownership of large, privatized companies, who decided almost everything — to the extent that they agreed at all.

When Vladimir Putin came to power in 2000, he was a consensus candidate, one whom many in the then-elite could agree to as the head of state. Putin’s job was to protect elite members from being attacked by each other. And he managed this, helped by a high oil price.

“Today, people whose background is from the security services and the military have become the strongest elite in Russia,” Østbø says.

Vladimir Putin himself originally comes from this group, called siloviki. A combination of political and economic factors at home and abroad has meant that these people now dominate the political scene, Østbø says.

The third elite is a group of leaders in the state bureaucracy. But these are the junior partners among the three elites who rule today's Russia.

“Much of the work Putin has to do when he gets up in the morning is about preventing these clans from attacking each other. Something like this happened in the 1990s,” Østbø said.

Unwritten rules for distributing money to the richest

During Putin’s reign, unwritten rules have determined how resources and wealth are to be distributed among the three Russian elites.

Much of President Putin's workday is dedicated to ensuring that as much of what happens between clans as possible is predictable.

“But Putin cannot sit forever and in recent years he has played a slightly more withdrawn role, which has resulted in more unrest in the elites,” says Østbø.

Rivalry creates uncertainty

“Everyone who undertakes economic activities of a certain size in Russia belongs to one of these three clans,” says Østbø.

“But the rivalry between the clans in the Russian power elite is constantly creating uncertainty about the future.”

This in turn creates a lack of constructive reinvestment of money in the Russian economy.

The people in Russia's elites are also unable to agree on any kind of vision for Russia's future.

Another obstacle to economic growth is that everyone knows that the best way to make money in Russia is to get their claws in a large state contract.

“But these contracts always go to Putin's confidants,” Østbø says.

At the same time, the situation makes it risky to start private projects over a certain size. This also helps slow down economic growth.

Constant conflict with the West

Vladimir Putin and the Russian power elite need something that can bind the Russian nation together.

Here, Putin and his cronies rely on Russian patriotism and the cultivation of the notion that the country is constantly threatened by the West and NATO.

At the same time, this presupposes that Russia is constantly in conflict with the West. But this situation again destroys Russia's position internationally — as well as the prospects for the country's economy.

Russia is a much larger country than Norway, but Russia's total economy (GDP) is now only just 3.5 times larger than Norway's.

Russia's GDP is smaller than the combined economy of the five Nordic countries.

It is also clearly smaller than the economy of a country like Italy and only slightly larger than Spain's. China's GDP is now almost ten times that of Russia.

Ten years of stagnation

“The last decade has been a period of economic stagnation in Russia,” Østbø says.

Many years of low oil prices have also meant less money to distribute among the elite groups. This is constantly creating challenges for President Putin.

“Even though unemployment is under control, the whole system is characterized by a lack of reforms and innovation,” Østbø said.

“On top of this come the sanctions from the West after the invasion of Ukraine, without the sanctions being the most important in causing Russia's economic problems,” he said.

Tones down Putin's power

Østbø and his research colleagues consequently don’t think that President Vladimir Putin is an almighty 'tsar' who dominates the country both politically and economically.

“Perhaps he’s not the cunning strategist he is often portrayed as being in the West,” Østbø said. “Much of what is happening in Russia illustrates Putin's lack of control.”

If something is to change, Russia must implement economic and political reforms. The problem is that these kinds of reforms can quickly threaten the balance of power between the elites. This in turn could threaten political stability in Russia.

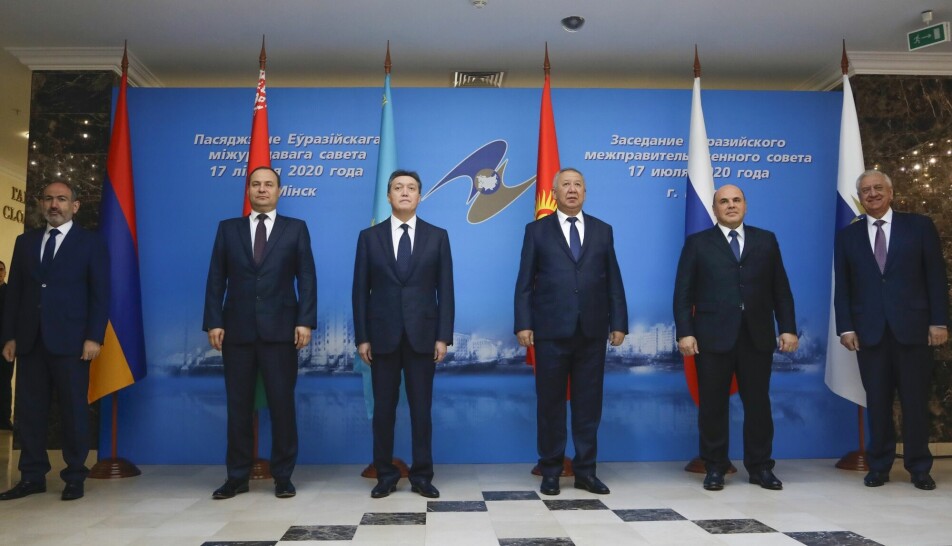

The failure of the Eurasian Economic Union

Part of the gloomy picture is that President Putin's major project, the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), comprising Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia is on the way to become a fiasco.

The agreement, which entered into force on 1 January 2015, was intended to create economic integration and establish a common market with free movement of goods, services, capital and labour among the member countries and the 180 million people who live there.

In a blog post from the American Kennan Institute, researcher Evgeny Troitskiy at Tomsk State University in Russia says the Ukraine crisis is what destroyed the EEU. After Russia invaded its neighbouring country, it put a monkey wrench in any attempt for more economic cooperation between the partners from the former Soviet Union.

Plans put on hold

When the countries in the EEU aren’t able to keep the other country’s agricultural products out of their own country with tariffs and quotas, they have used inventive hygiene rules and veterinary checks instead.

The plan is now to establish a common market for oil, gas and electricity by 2025, but much remains to be done here. Liberalization of the financial sector has also been postponed until 2025.

The EEU countries have come the furthest in cooperation on research, tourism and the free movement of labour.

Nevertheless, Troitskiy believes that Russia will have to use more and more sticks than carrots in its economic relations with neighbouring countries. And if Russia fails to resolve its deadlock with the West following the Ukraine invasion, then the EEU is doomed to inertia and stagnation.

Researchers Golam Mostafaa and Monowar Mahmood also observed, in a 2018 study in the Journal of Eurasian Studies, that the EEU had achieved very little. Russia's declining economic growth and distrust of the Russians from the smaller participants in the wake of the Ukraine invasion have also been identified by these researchers as explanations for the EEU failure.

Russia conference in Oslo

There is broad agreement among economists and political scientists who study Russia that something must be done about the country's economy.

But the elites in the country are unable to agree on what should be done or how it can be done.

“Powerful players in Russia can’t even agree on fairly simple things like allocating radio frequencies to a new 5G network,” Østbø said. “So this work is going very slowly.” A separate case study on precisely this issue has been done by RUSECOPOL.

On 2 December, the research project will arrange a conference at the House of Literature in Oslo, which is open to everyone.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

The RUSECOPOL project website.

Jardar Østbø: State, business, and the political economy of modernization: introduction, Post-Soviet Affairs, 2021.

Andrei Yakovlev: Composition of the ruling elite, incentives for productive usage of rents, and prospects for Russia’s limited access order, Post-Soviet Affairs, 2021.

Evgeny Troitskiy: The Eurasian Economic Union at Five: Great Expectations and Hard Times, blog article at the Wilson Center, 2020. The article.

Golam Mostafa and Monowar Mahmood: Eurasian Economic Union: Evolution, challenges and possible future directions, Journal of Eurasian Studies, 2018.

———