Dictators are doing it for themselves - but has Putin taken it too far this time?

The political science is clear: Putin is a dictator. The same science is also clear on this: a financial crisis is dangerous for a dictatorship.

The data and the indexes are clear:

“Russia has become a dictatorship”, says Carl Henrik Knutsen.

Knutsen, a professor at the University of Oslo, is a political scientist and an expert on dictatorships and democracies.

He has for many years been one of the Principal Investigators of the Varieties of Democracy project, in which 3000 researchers collaborate in order to code huge amounts of data and information about democracies and dictatorships in the world.

V-Dem, as the international project is abbreviated, is “one of the largest social science data collection projects on democracy in the world”. Having collected data since 2008, the results of the project make us better able today to understand both dictators and their dictatorships.

Is it in Putin’s interest?

In a western democratic country like Norway, it's easy to think in terms of the country’s interests. Norwegians will talk about whether or not something is in the best interest of Norway, or what’s in the best interest of other countries, like Russia for that matter.

“This would be the correct way of thinking about things in Norway”, Knutsen says.

“However, in a country like Russia, the concern often isn’t what is in the country’s best interest. Rather, it’s about what the leader’s best interest is. In other words: what’s in the best interest of Vladimir Putin”, the political scientist explains.

“It’s Putin and his interests that determine whether we get peace, or war”, he says.

More crises in dictatorships

When the conservative government in Norway, led by Erna Solberg, lost the election and was replaced by a labour government led by Jonas Gahr Støre – most things in Norway continue as they were.

This would be the norm for most democratic countries.

“But if you get a new dictator in, who takes over from another dictator, then you may see great changes in the country”, Knutsen says.

This often contributes to making it far more common with crises and financial turmoil in dictatorships compared to democracies. The researchers now have historical figures that illustrate this.

“When the democratic control which keeps the leader or leaders in a democracy in check is lacking, then those who rule a country can do a lot of strange things”, Knutsen says.

Knutsen himself has for instance looked at the correlation between dictatorships and high skyscrapers.

These dictator-skyscrapers are often very impressive to look at, but they are also very often empty inside – like for instance the new skyscrapers in Moscow.

According to Wikipedia, at 462 metres, the Lakhta Center of Saint Petersburg was the tallest skyscraper in Europe as of 2020. Moscow is home to 7 out of the 10 tallest skyscrapers in Europe.

Can Putin be removed?

A more serious issue than tall skyscrapers is when the dictator decides to go to war.

“In Norway, a prime minister would be voted out if he or she went to war without the support of the people. In a dictatorship like Russia, the leader is not held accountable in that same way”, Knutsen says.

He fears that in today’s Russia, there are few who are able to stop Vladimir Putin.

“If Putin is wrong about Ukraine and this invasion spins out of control for him, then things might happen. But this remains to be seen”, says the professor.

Elections to maintain a façade

In the indexes that Knutsen and his colleagues use to compare dictatorships and democracies, Putin’s Russia has qualified as a dictatorship for some time.

“Russia isn’t quite Saudi-Arabia or North-Korea. In Russia they hold elections and there are institutions that are reminiscent of those you would find in a democracy”, Knutsen says.

“But this is mainly a façade”, he maintains.

Most dictatorships have such a façade.

“Even if there are elections in Russia, and even if there is something similar to an election campaign period, there is so much cheating and repression, that nobody is in any doubt as to whether Putin will remain in power”, Knutsen says.

Different kinds of dictatorships

Dictatorships come in different forms and shapes.

“A dictatorship can be anything from an authoritarian monarchy, which we see quite a few of in the Middle East, to single-party dictatorships like China has been for many years”, Knutsen says.

“Russia has now moved quite far in the direction of what us researchers refer to as a personalistic dictatorship”, he says.

As the name suggests, this is a dictatorship with one person at the top, who enjoys a lot or seemingly unlimited power.

Knutsen points to China as an interesting parallel.

“China has for the last few years moved away from being a single-party dictatorship”, the professor says.

“At the moment, the leadership in the communist party is to a lesser degree in control of the country. Instead, also China is moving toward becoming a personalistic dictatorship where the dictator Xi Jinping is securing increasing powers for himself”, Knutsen says.

Personalistic dictatorships

In personalistic dictatorships, the leader at the top is met with few restrictions.

“Institutions and rules for running a country and society matter less in countries like these. It is either the leader alone or the leader along with a small group of men around him that make all important decisions”, Knutsen says.

Russia has gone very far in the direction of becoming such a dictatorship, according to Knutsen.

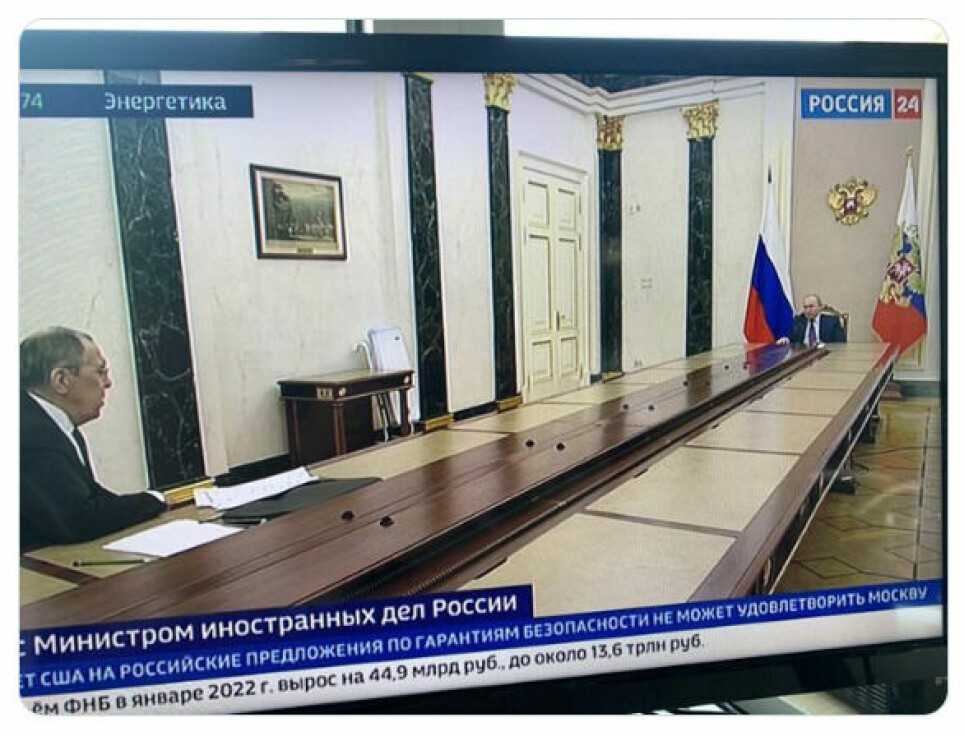

It is now Putin alone or Putin and a small group of men who make the important decisions.

This may have also been the case when it came to the decision of invading the neighboring country Ukraine.

The Duma, the Russian assembly, still meet. But only in order to give its blessing to that which the dictator has decided. Even if he has decided to do something as extreme as going to war against Ukraine.

- READ MORE about how Putin is now surrounding himself more and more with people who confirm his world view: Russia has become a classic dictatorship

Are democracies on the retreat?

Research on democracy and dictatorships is a field where the researchers can now give us much more certain answers than they could just ten years ago.

The researchers now clearly see that democracy and dictatorship ebbs and flows like a wave.

“We have a lot of data to support this conclusion”, Knutsen says to sciencenorway.no.

Historically there have been three large democratic waves over the past 200 years. The last period in which democracy was on the rise was from the mid-1970s and up until the mid-1990s.

Democracy hit peak in the world ten years ago, in 2012.

After this, the level of democracy in the world has receded.

In large countries like China, Russia and India, leaders in office and governing parties have tightened their grip on power. India has for a long time been the world’s largest democracy, but various reports from last year cited in a BBC-article ranked the country as a “partially free democracy”, a “flawed democracy” and an “electoral autocracy”.

In Myanmar, a junta has taken power through a military coup. The same has happened in Sudan. There are fears that Jair Bolsonaro will cling to power in Brasil, if he loses the election this coming fall. Just a couple of weeks ago, Bolsonaro was in Russia to meet with Vladimir Putin.

Translated by: Ida Irene Bergstrøm

References:

V-Dem Institute: «Democracy Report 2020».

Carl Henrik Knutsen et al: Introducing the Historical Varieties of Democracy dataset: Political institutions in the long 19th century, Jorunal of Peace Research, mai 2019. Abstract

Haakon Gjerløw and Carl Henrik Knutsen: TRENDS: Leaders, Private Interests, and Socially Wasteful Projects: Skyscrapers in Democracies and Autocracies. Political Research Quarterly 2019. Abstract.

------

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no