The HIV virus can turn white blood cells into tiny virus factories.

Untreated, the disease destroys the immune system.

But it is possible to stop the virus.

How do HIV medications work?

As long as HIV-positive individuals consistently take their medications, they are not infectious.

Ever since the HIV virus was discovered in 1984, researchers have been searching for a cure. So far, to no avail.

However, a silent medical revolution has forever changed HIV. From being a certain death sentence, HIV-positive individuals in Norway can now live well with the disease and avoid transmitting it to others.

So how do the medications manage to keep HIV in check?

To answer that, we need to understand the virus itself.

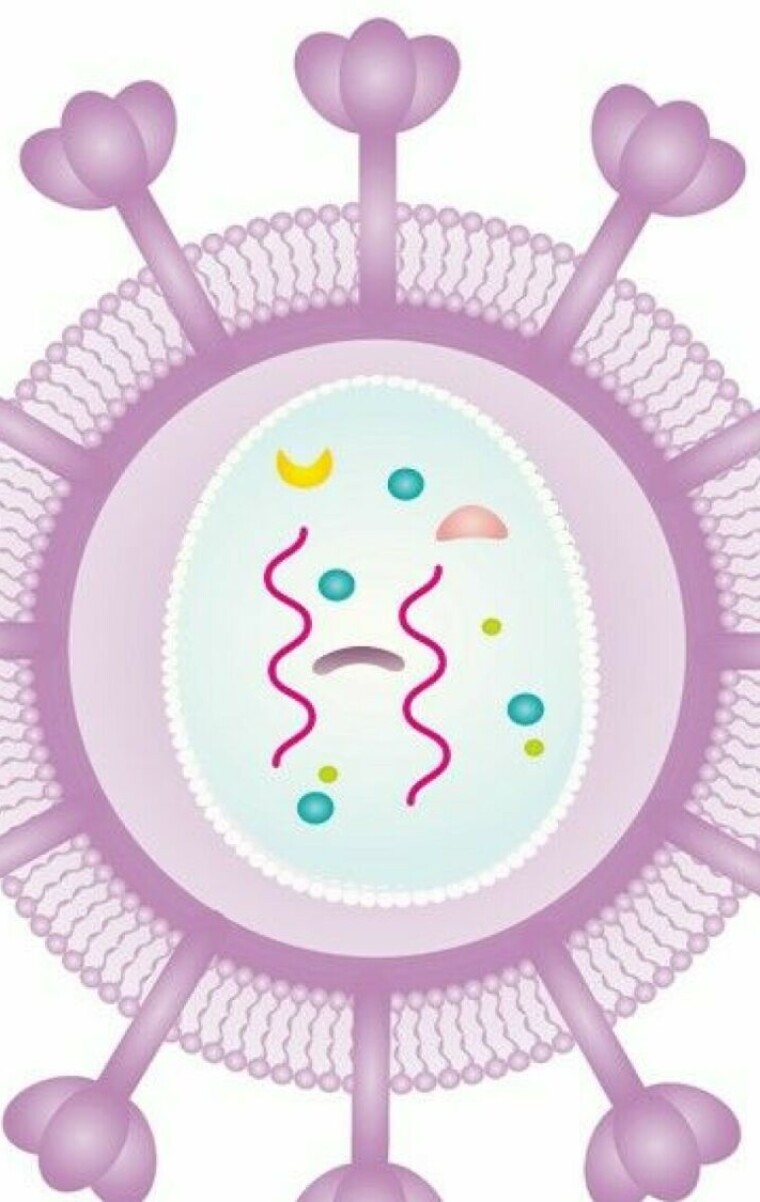

HIV is an encapsulated virus with spike proteins around the envelope.

Inside, there are a few enzymes and a short genetic code.

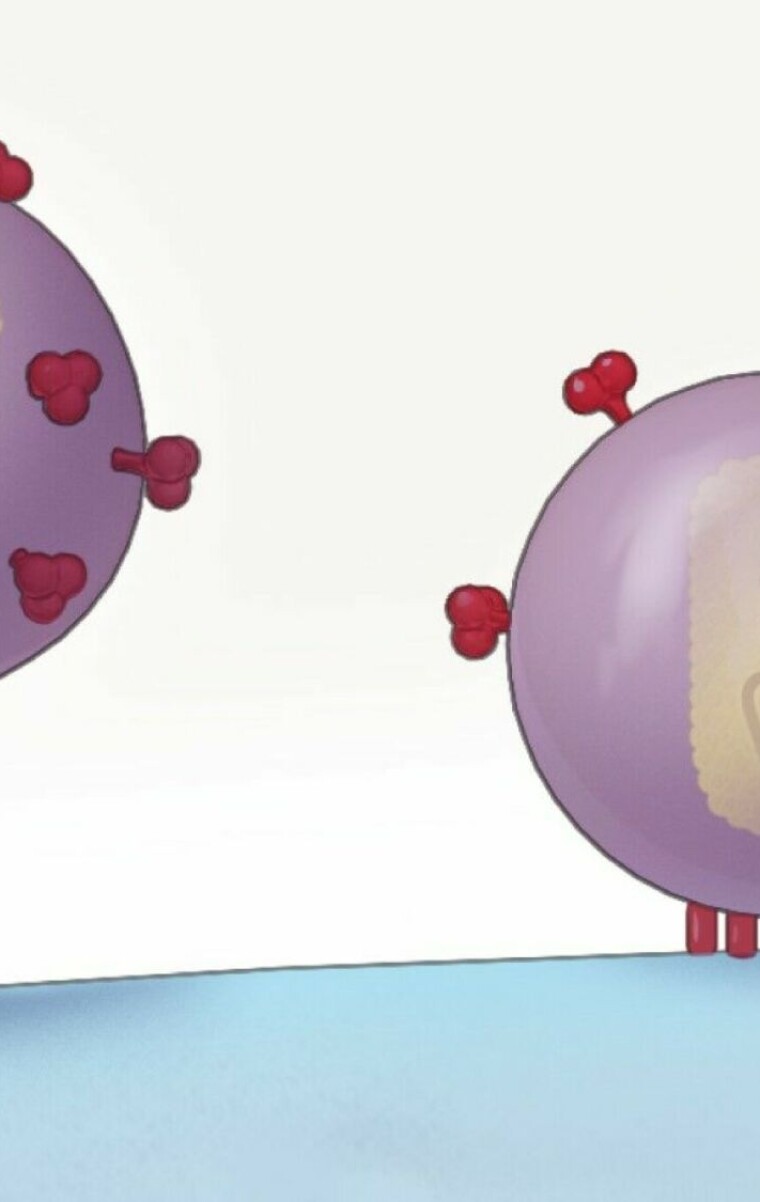

When the HIV virus attacks the body’s cells, it behaves in the same way as other viruses.

First, it attaches itself to host cells. Then it injects its genetic contents.

Weakens the immune system

Virus from a person with untreated HIV can be transmitted through blood, the penis, or the vagina.

In order for the HIV virus to enter another person’s body, it has to be transmitted through blood or mucous membranes.

The HIV virus attacks a specific type of white blood cell called helper T-cells.

The more of these cells the virus hijacks, the more weakened the immune system becomes.

Untreated, HIV can lead to AIDS.

Stays in the cells

So what makes the HIV virus so difficult to get rid of?

The secret lies in the genetic code.

It is primarily made of RNA, similar to the viruses for the common cold, influenza, and Covid-19.

But unlike other viruses with this type of genetic material, the HIV virus has a special superpower.

It can transform the fragile RNA code into more resilient DNA.

And then the decisive step occurs.

The HIV virus sneaks its DNA code into the host cell DNA. It stays there.

Once the cell has been hacked, the virus takes control.

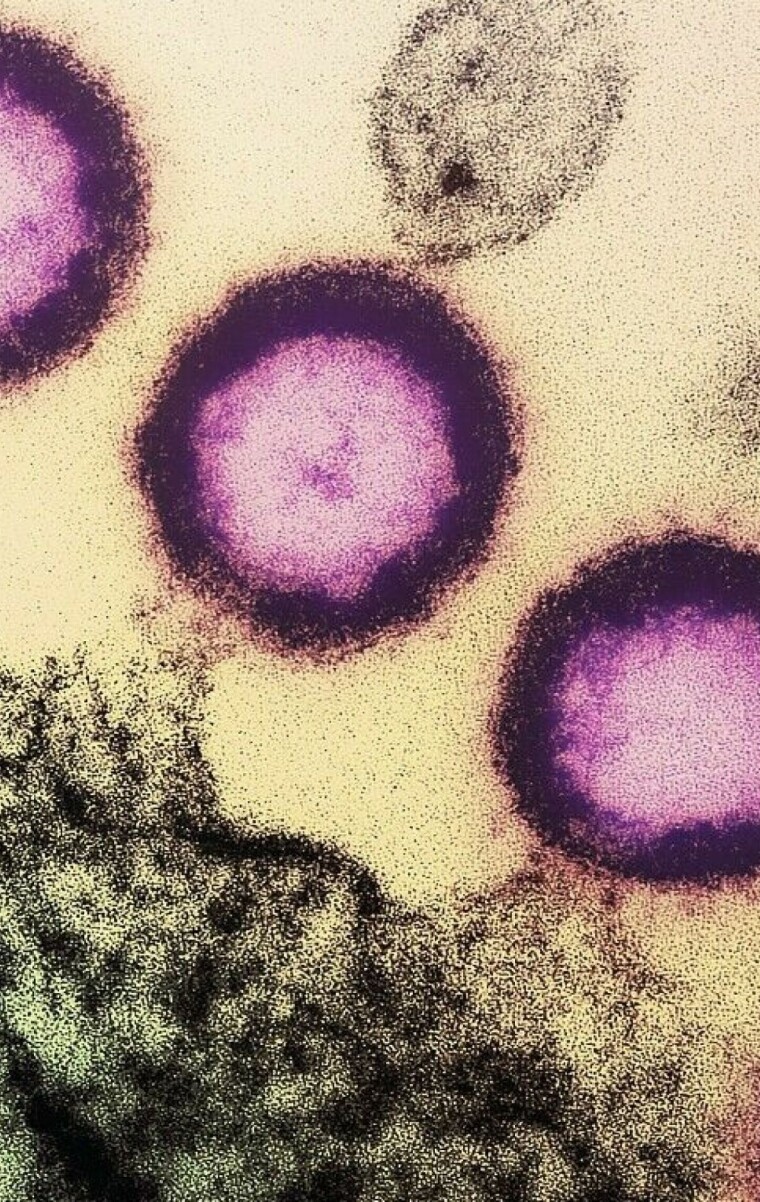

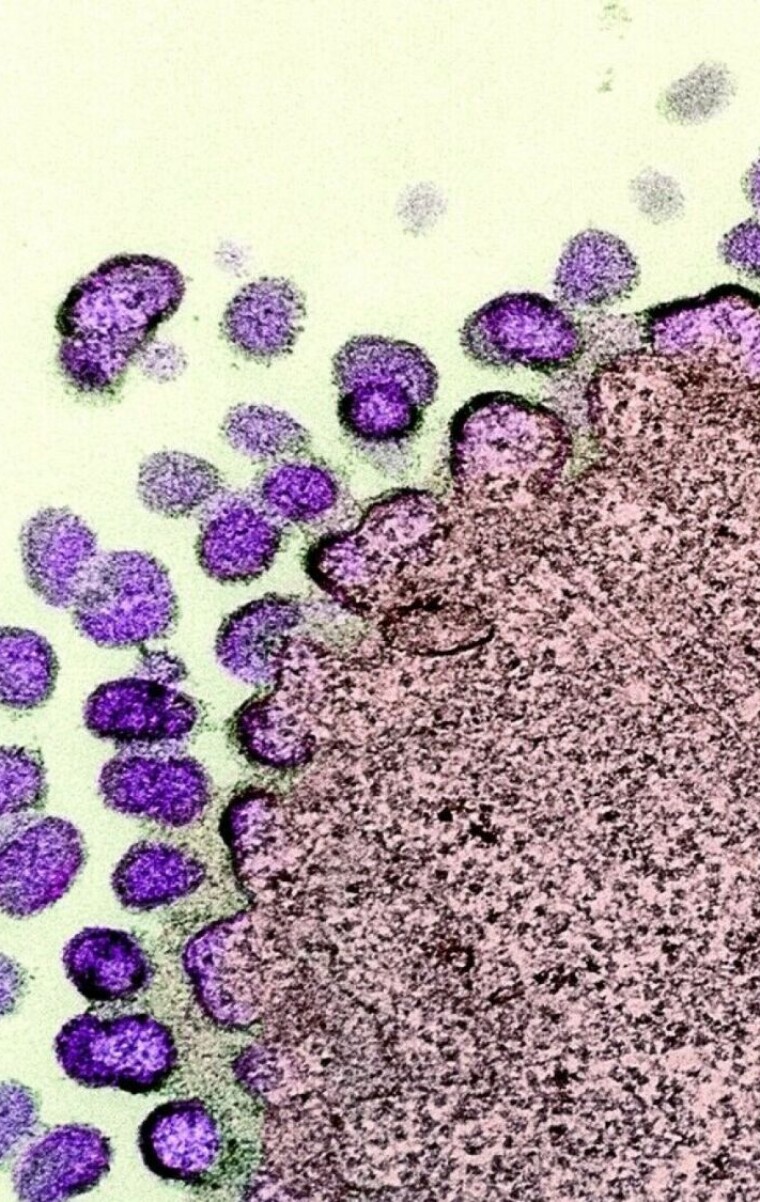

If we zoom out, we can see a white blood cell that has been infected by HIV.

The immune cell has been instructed to do something other than what it is supposed to do.

From within, new viruses sprout as small buds, coloured in purple.

Attacks multiple points simultaneously

This doesn’t happen if you take medication.

So how do the medications stop HIV from turning white blood cells into virus factories?

Researchers and the pharmaceutical industry have aimed to target specific points in the HIV virus’s life cycle.

But keeping the disease in check without the virus developing resistance only happened once medications that targeted multiple points simultaneously came on the market, Bente Magny Bergersen tells sciencenorway.no.

She heads the clinic that treats HIV patients at Oslo University Hospital Ullevål.

How the medications work

Here are some of the most important breakthroughs:

- The first medication hit the market in 1987. It blocks the transformation of the genetic code from RNA to DNA.

- In the mid-1990s, a medication that prevents the virus from making new copies of itself was introduced.

- By the late 2000s, a medication that blocks viral DNA from integrating into host cell DNA was developed.

Several new generations of these medications, along with others, have since been released.

Prevention with PrEP treatment

The most common HIV treatment in Norway is one pill a day that combines two of these medicines.

Sticking to this treatment will keep the virus inactive, and you will avoid transmitting it to others.

People in risk groups can receive preventive PrEP treatment containing one of the same HIV medications given to HIV-positive individuals.

Belief in a cure

Even though the disease can now be kept in check, it cannot yet be cured.

Immune cells with viral DNA hide somewhere in the lymphatic system, says Bergersen.

But the infectious disease specialist believes that a cure will come.

A promising approach is immunotherapy combined with HIV medications. The idea is to train the infected person's own immune system to find and kill the hidden cells.

Pictures:

Close-up microscope image of purple virus bursting out of a cell: NIAID, CC BY 2.0

Illustration of HIV virus with RNA and enzymes inside: Julee Ashmead / Shutterstock / NTB

Illustration of HIV virus attaching to immune cell: Fvasconcellos / Wikimedia commons, CC BY 2.5

Illustration of DNA: peterschreiber.media / Shutterstock / NTB

Close-up microscope image of purple virus bursting out of a cell: NIAID, CC BY 2.0

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no