The twins from Tynset and the mystery disease

Everything seemed fine with the twins from Tynset — until they gradually lost their vision and the ability to walk. After 50 years, doctors and scientists have finally solved their medical mystery.

It happened gradually.

As children they were fine. They joined their father for long walks in rugged terrain. They were tops in javelin throwing. And they were already doing simple calculations before they started first grade.

Nevertheless, something was not quite right.

Their vision began to fail. Their legs grew stiffer and stiffer.

By 1970, when they were 18, the boys travelled from their home in Tynset to Oslo, to spend a whole month at Oslo University Hospital for a series of unpleasant tests.

The hope was that someone would be able to tell them what was wrong — and treat them.

But that was easier said than done. The brothers had a highly remarkable combination of symptoms. Having stiff legs is not so unusual. But combined with vision loss, it's very rare.

And there was one more thing: they had amazing memories. They were so good that one day a neuropsychologist would do a test to measure precisely how exceptional their memories actually were.

But that was far in the future.

At Oslo University Hospital in 1970, no one had any idea that the twins were at the beginning a nearly fifty-year-long odyssey to understand what was wrong.

It was a quest that would extend far beyond the two brothers, to include a series of researchers who would do their very best to solve the mystery of the twins from Tynset.

And it’s a story that clearly shows just how far medicine has come in the last half century.

When the first samples were taken, the technology and the knowledge that would be needed to diagnose the boys simply did not exist.

It was only in 2016 that the answer would begin to come clear, provided by the combination of modern genetic tests and an interdisciplinary team with expertise in neurology, genetics, molecular medicine and structural biology.

First-hand experience

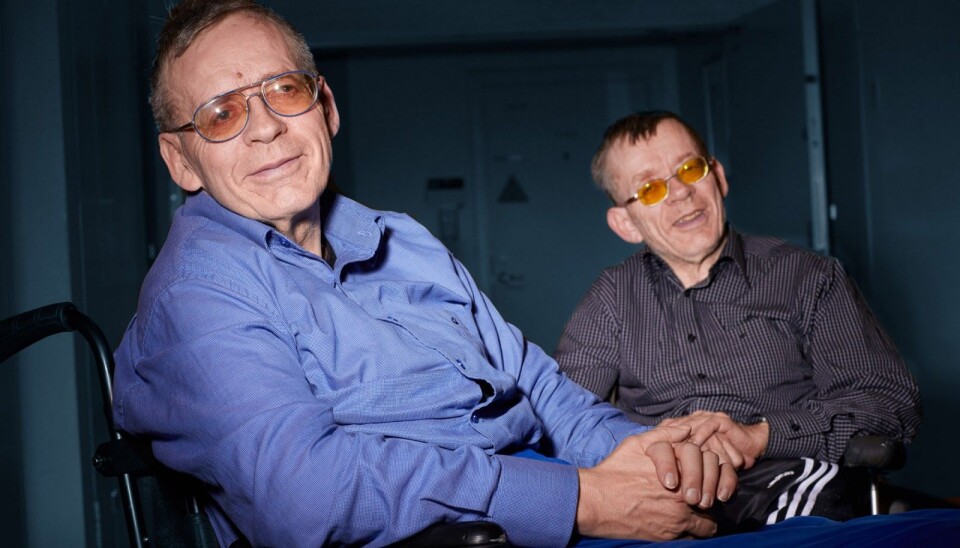

Bjørn and Tor Olsen have had first-hand experience of how medical technology has changed over the past fifty years.

Some of their stories are enough to send shivers down your spine. Like when doctors wanted to get images of their brains.

“There was no such thing as MR and CT scans at that time. Instead, we had to have tests done with air,” Bjørn said.

It worked like this: the doctors would stick a needle in the bottom of the spine and then pump air into the brain. The air acted like a contrast medium when the doctors took x-rays of the boys’ brains. Needless to say, it was extremely unpleasant.

But the twins say as long as they have each other, they don’t mind. They have a hundred stories that show much they mean to each other. And they have helped each other live active lives in spite of ever-increasing physical challenges.

Instead of talking about the difficulties in their lives, they talk about everything they've done.

Tests, but no answers

The unpleasant tests at Oslo University Hospital eventually resulted in a research article that described their puzzling symptoms, published in 1972. But the article raised only questions, not answers.

In the meantime, the brothers didn’t let their symptoms slow them down. They ran track and threw the javelin.

Eventually, the twins moved to Oslo, and began at the university. They continued with a very active lifestyle in addition to their studies.

"We noticed that the more we ran, the less resistance there was in our muscles and eventually they worked reasonably well,” said Tor.

Nonetheless, their eyes and legs gradually became worse. In 1989, Tor and Bjørn had to go back to Oslo University Hospital for several weeks of tests — but they still did not get any answers.

A heredity disease

Chantal Tallaksen is a professor of neurology at Oslo University Hospital who has been following Bjørn and Tor since 2003.

When she first met the twins, she thought they must have a kind of hereditary spastic paraparesis, which leads to paralysis and stiffness in the legs. But tests proved her wrong.

What was almost certainly clear was that their illness was hereditary. Both of the twins had it — and they were identical twins, meaning they had developed from a single egg.

But what gene gave this striking combination of physical weaknesses and an amazing memory?

In the 1990s, genetics had advanced to the point that researchers could look for a limited number of known mutations in the genes of the twins. But the researchers were unable to find any matches.

"I thought that before I retire as a researcher, I will figure this out," says Tallaksen.

A family in Turkey

It took large-scale DNA sequencing to finally solve the riddle of the twins from Tynset.

After combing through roughly 25,000 genes, Tallaksen and a group of researchers from different fields were left with a couple of possibilities that could have explained the twins’ disease.

In the end, they found a gene where the twins have two mutations —one from their mother and one from their father.

A similar mutation in the same gene had actually been described before — in one family from Turkey. There, the affected family members have the same problems as the twins with their vision and legs.

On a February day in 2017 — or on the 27th of February at 1 p.m., as the brothers would say — the researchers went to the brothers with the news.

A link to memory

Although not proven, scientists believe that the mutations might also explain the twins’ extraordinary memory.

Studies in mice show that this particular gene is linked to memory. The gene is known to create a protein that makes up one to two per cent of all brain proteins, which is a lot. But the mutations in the twins’ gene also change the protein the gene makes.

Researcher Paul Hoff Backe made a structural model of the protein with the mutations the twins have. It suggests that the mutations cause the protein to become more active.

"Maybe the increased activity helps maintain functions like memory," Backe said. In that case, the mutations—the changes in the gene —actually convey an advantage.

Tor and Bjørn Olsen are happy that they’ve finally gotten an answer about their mysterious disease. But they also find it surprising.

“I would have never thought this is all due to one gene,” Bjørn said. “I thought it had to be tons of them.”

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no