Pregnancies can alter eating disorders

A pregnancy can entail either a risk or a hope for women with eating disorders. Many get rid of the disease for long time. For others, pregnancy is the beginning of their problems.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

A pregnancy involves enormous changes, physically, psychologically and socially. So there is good reason to suspect it can also affect any eating disorder a woman might have.

This element of change has been shown in various studies. For many – especially women with bulimia nervosa – pregnancy represents a good period with fewer symptoms.

But what happens afterwards?

Norwegian researchers have used data from the comprehensive Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study to find out how women with eating disorders were doing 18 months and 36 months after giving birth.

Many regain their health

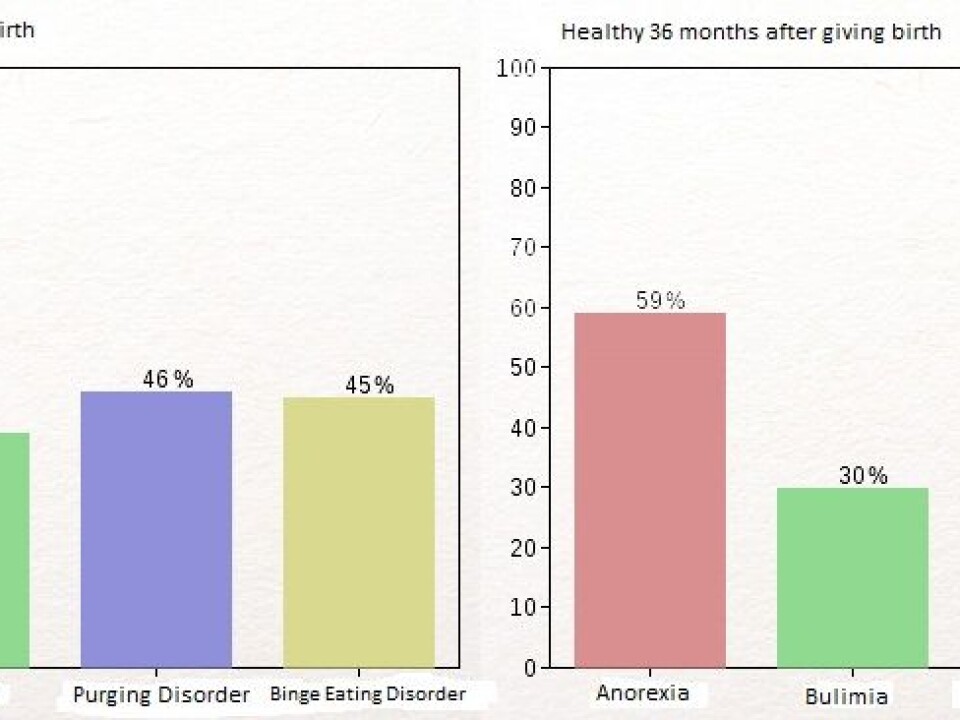

The results showed that many stay rid of their disorder for a long time. Among anorectics, over half were still free of their symptoms when their child reached the age of three. A third of the mothers who had bulimia were also healthy at this point.

“These are fairly high numbers,” says Cecilie Knoph of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, who was the main author of the study.

She cannot say with certitude why the disorders change during pregnancy.

Perhaps it is because pregnancy often coincides with a generally positive time of life. Many have entered stable relationships and are enjoying their lives.

Researchers have previously found that such health improvements during pregnancy are linked to a rise in self-confidence and satisfaction.

Perhaps pregnancy has a more direct effect. When a woman’s focus is on the needs of her foetus it is easier to supress undesirable eating behaviour.

“Hormonal changes can also be at play, perhaps particularly with binge eating disorder,” says Knoph.

Hormones

Earlier research has indicated that women’s symptoms of binge eating disorder can coincide with their menstrual cycles. Lab experiments with rats have shown that similar hormones link with food intake.

It’s possible that hormones released in pregnancy have an effect on the disorder. This might explain why some women first experience binge eating disorder in connection with a pregnancy.

Can hormones have triggered a disposition for such diseases, just as hormonal changes in puberty could be linked to other eating disorders?

Many of the women who were stricken with binge eating disorder during pregnancy lose it after giving birth. But some continued to be sick in the following years.

Knoph says this is a point we need to be aware of.

“Although many with eating disorders get better during and after their pregnancies, we should remember that many others continue to be plagued by their disorders,” she says.

“And they need to be followed up.”

Eating disorders affect the family

“We know that eating disorders can have an effect on the parenting role,” says Knoph.

Mothers with eating disorders often have problems with breastfeeding and are more likely to use food as a reward. These women also worry more about their children’s weights and are upset at mealtimes because they find the situation stressful.

These mothers are also scared of transferring their eating disorders to their kids.

So far, researchers don’t know how children are affected. But there is plenty of documentation showing that eating disorders run in families and much is probably hereditary.

“So the children might have a genetic disposition and it can be unfortunate for them to be in an environment marked by eating disorders,” says Knoph.

This is yet another reason to give extra support to mothers with eating disorders.

Many go undiagnosed

Knoph thinks it’s essential for the health services to follow up women who are plagued by eating disorders during pregnancies and afterwards.

This is also crucial for decreasing the risk of complications that often follow in the wake of such disorders, for instance premature births or abnormal birth weights.

“Good treatment is available and many can get well,” says Knoph.

But as it stands, many of these mothers will make it through their pregnancies without midwives and other health personnel becoming aware of their eating problems. These entail taboos and women are sometimes reluctant to tell obstetricians and others about them during their pregnancies.

Nor are there any routines for health personnel to ask them about possible eating disorders. Knoph thinks midwives and others in contact with pregnant women should be trained to spot these women and offer help.

She also urges pregnant women to not hesitate about revealing their problem to the midwife or their MD.

“This is the first step toward getting better,” explains Knoph.

---------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling