Are Norwegians really the sickest in the world?

When people from Sweden or other countries with lower sickness absence rates than Norwegians start working in Norway, their absence becomes similar to ours. What’s going on with Norway?

Ulf Andersen is head of statistics at the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) and can compile statistics on almost anything.

He finds the statistics on sick leave based on the country of birth particularly interesting.

It shows that Swedes who live and work in Norway have roughly the same sickness absence rates as Norwegians.

“Many of those employed in Norway from other countries are labour immigrants. They are not sick people coming here to work,” he says.

This may indicate that there is something in Norway that contributes to the rise in sickness absence, Andersen believes.

Is health the problem?

This could be due to many factors, notes Andersen.

“It could be due to waiting times in the healthcare system, doctors' sick leave practices, attitudes in the population, NAV’s ability to monitor sick leave follow-up, or how companies facilitate sick leave,” he says.

According to Andersen, it likely has little to do with health.

He points to the paradox: Norway is among the world's richest countries. Citizens have a long life expectancy and good health. The country’s healthcare system has been voted the best in the world.

“You wouldn't believe it when you look beyond the population, but we have the highest sickness absence rate in the whole world,” he recently said in an interview with Parat24, an online newspaper associated with the labour organisation Parat.

Only twice in 20 years

Yes, Norway’s sickness absence rate is alarmingly high. But this is not really new, Ulf Andersen points out.

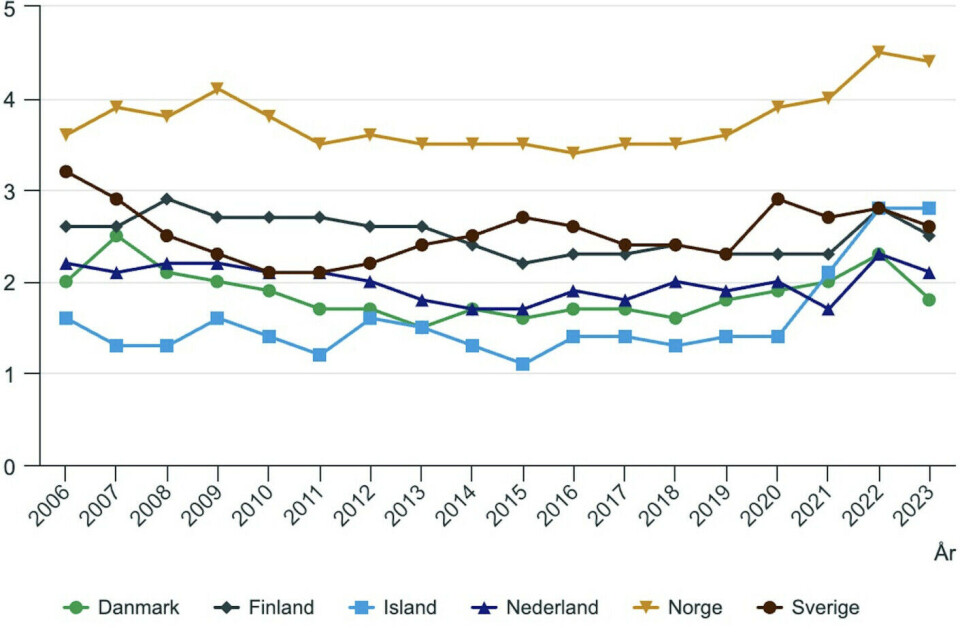

He has numbers going back to 2006 which show that Norway has had the highest rate in the Nordic region every year in terms of the proportion of employed people absent from work for one week due to illness.

But at the moment, the gap between Norway and other countries is wider than it has been in a long time.

“Norway has only had this level of sickness absence twice in the last 20 years. This was when we had swine flu and during the Covid-19 pandemic,” says Andersen.

Something has happened in Norway

Something has indeed happened in Norway during and after the pandemic.

But why has it only happened in Norway?

Norway’s neighbouring countries, Sweden and Denmark, have seen a decline in sickness absence after the pandemic. This is also true for most other countries in Europe.

Simen Markussen, director of the Ragnar Frisch Centre for Economic Research, also finds this hard to explain.

“It’s probably a mix of several factors,” he says.

Markussen points out that Norway has high employment, a generous sick pay scheme, and a relatively long sick leave period of a whole year.

“But I could have given the same answer before the pandemic too. It was exactly the same back then,” he says.

Not easy to compare

Can Norway's high sickness absence be explained by some confusion in the statistics?

It’s not that easy to compare sickness absence across countries, admits Ulf Andersen.

There are several reasons for this.

Firstly, the systems in different countries are different. There is no other country that has Norway’s scheme, with 100 per cent reimbursement up to a certain level, one year's right to sick pay, and no waiting days.

“It would be like comparing, if not apples and pears, then at least green apples with red apples,” says Andersen.

Sickness absence is not measured in the same way

But that is only one of the challenges.

The second problem is that no country measures sickness absence the same way Norway does.

Statistics Norway (SSB) produces statistics on sickness absence in Norway. They do this in collaboration with NAV. The agency has good control over medically certified sick leave in Norway. All sick leave reports that go through a doctor are recorded there.

What about self-reported sickness absence?

There is no central registration for self-reported sick leave in Norway, however.

Only you and your employer know how many days you will be away from work before you are given doctor-approved sick leave.

However, the statisticians have solved this problem. SSB conducts a survey every quarter where they ask people if they have had self-reported sick leave in the last three months.

When SSB and NAV combine these two sources, they get a picture of the total sickness absence.

Robust and sound statistics

It’s complicated to measure sick leave, according to Andersen.

This is partly because not everyone works in a 100 per cent position.

If a part-time worker is sick, this can’t count as much as sickness absence for a full-time employee. The same applies to someone on partial sick leave.

The way to correct this is to convert everything into what statisticians call ‘lost workdays.’

“When we now say that sickness absence in the last quarter was 7.1 per cent, we aren’t actually talking about people who have been on sick leave, but rather the amount of lost workdays,” he says. “This is a very robust and reliable statistic, but no one else uses this type of statistic."

Most viewed

"Could sickness absence in other countries fly under the radar because it's not recorded as thoroughly as in Norway?"

“That’s unlikely,” he says.

Implemented in many countries

The only way we have to compare sickness absence across countries is through statistics from SSB's Labour Force Survey (LFS), Andersen says.

This survey is conducted every quarter in many countries around the world, including in the EU/EEA. Countries like the UK, Canada, the USA, and Australia also have similar surveys.

In these surveys, all statistics agencies ask the exact same question among the employed:

Have you been away from work for a full week due to illness?

“These are the comparisons we use when we say that Norway has a very high sickness absence compared to other countries,” says Andersen.

Different regulations

Tonje Køber, head of the division for labour market and wage statistics at SSB, believes that the figures between the European countries are comparable.

“The data is collected according to the same methodology and definitions,” she says.

But one thing that can affect the figures is different regulations in the various countries.

This can make it problematic to compare the level of sickness absence between countries, even in the Nordic region, she believes.

In Norway, you can be on sick leave for up to one year without losing your job. In Sweden and Denmark, workers can lose their jobs more quickly due to lower job security and enter other schemes if they require long-term sick leave.

“Countries with less job security than Norway will have lower sickness absence, as people on long-term sick leave may lose their jobs and move to other welfare schemes. They would then not be counted in the sickness absence statistics,” she says.

Not due to higher employment

In the sickness absence debate, it has often been said that Norway has higher sickness absence because employment levels are so high.

Simen Markussen rejects this argument.

“Norway doesn't have higher employment than the countries we usually compare ourselves with, Sweden and Denmark. In fact, Sweden has higher employment than us,” he says.

Markussen thinks the argument about high employment is used too often in this debate.

“It's clearly relevant if we compare ourselves with countries that have very low employment, like some countries in southern Europe. But it doesn't make sense when we compare ourselves with our neighbouring countries,” he says.

Not important to rank countries

Tonje Køber at SSB does not think the most important thing in the discussion of sickness absence is where Norway ranks.

“The challenge for Norway now is that we have increasing sickness absence and that these rates have stabilised at a higher level than before the pandemic. This is also different from our neighbouring countries and most European countries, which have seen a decrease in sickness absence after the pandemic,” she says.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.