This disease can suddenly make you behave very strangely. Afterwards you might not remember a thing.

Not everyone with epilepsy has seizures. And in a lot of cases, we don’t know why the disease occurs.

In theory, it could happen to any of us. At any time.

One moment you're heading down the sidewalk and sense peace and no danger. The next thing you know you could wake up in the middle of the road, with no idea how you got there.

Or suddenly a strange wave passes through your head, before you sense an intense smell of burnt car tyres.

Or you’re overcome with wild, inexplicable anxiety, just before you suddenly start staring straight ahead as you fumble with the fabric of your jacket.

Afterwards, you’re dazed and confused and wonder if you were behaving strangely. And whether the other people on the bus noticed you.

Many people develop the disease after they turn 65

All of the above descriptions are examples of epileptic seizures. About five percent of the population experience a seizure once in our lifetime.

Some individuals experience multiple seizures and are eventually diagnosed with epilepsy.

Epilepsy is actually one of the most common brain diseases and affects just under one person in a hundred. Around 40 000 people in Norway currently live with epilepsy. Many people develop the disease after they turn 65.

But what is epilepsy, exactly?

Why and how do seizures occur? And why are they so incredibly different from person to person?

At Norway’s National Centre for Epilepsy (SSE) in Sandvika outside Oslo, the researchers have good answers – but at least as many basic questions that they still do not know the answer to.

Incredibly complicated disease

“This has been a home for epilepsy patients for over a hundred years,” says Kaja Selmer, a researcher at SSE.

She says that the facility is quite special, as not every country has its own hospital for epilepsy.

But if you had to choose a disease that deserved a specialty hospital, epilepsy would be an excellent candidate.

Epilepsy is an incredibly complicated disorder. Just making the diagnosis can be extremely challenging. Although epilepsy is classified as a single disease, it can have myriad causes and many completely distinct symptoms.

You can't just take a blood test or a simple test and get a definitive answer. SSE conducts a thorough investigation and mapping in order to distinguish epilepsy from other types of seizures, to find out what might be causing the seizures and to determine how the patients should be treated.

Excessive electrical signals

Although epilepsy can manifest very differently in different people, one common mechanism underlies the disease for everyone, says Selmer: excessive electrical discharges in the brain.

Electrical discharges are the cornerstone of brain activity. This is how the brain cells send signals to each other.

But for some people the electrical signals go haywire.

Researchers Karl Otto Nakken and Mia Tuft explain it simply in their book Epilepsi – et vindu inn i hjernen (Epilepsy – a window into the brain):

A normal brain cell usually has a negative electrical charge on the inside. This is controlled by channels in the cell membrane, which can pump electrically charged particles in and out of the cell.

When the nerve cell is activated and needs to send a signal, the channels change the electrical balance so that part of the cell receives a positive electrical charge. This creates an electrical wave that races down the long nerve cell. The impulse is then transmitted to the neighbouring cell, and this is how the signal travels through the brain.

In an epileptic seizure, a mistake occurs in regulating the electrical charge in some of the nerve cells. They fire wave after wave, without any aim or meaning.

“The cells get hyper-irritable – trigger-happy as it were,” says Tuft.

It is easy to understand that such a wild flurry of electrical signals has consequences for the body, thoughts and emotions that the brain helps to control.

Brain location determines the symptoms

Uncontrolled electrical discharges in the brain are thus behind all epileptic seizures.

The symptoms can vary widely, depending on where the disturbances start and how far they spread.

Different parts of the brain work with different tasks. Some areas control movement in different parts of the body. Other parts of the brain are important for sensory impressions, such as sight, smell or taste.

People with epilepsy can have electrical disturbances anywhere in the brain. But exactly where the disturbances start varies from person to person. It also means that the seizures of two people with epilepsy can present very differently.

If a network of disturbed brain cells is located in the motor cortex, the seizure might begin with the twitch of an arm.

Disturbances in the sensory cerebral cortex can produce experiences of distorted smells, strange tastes or a tingling sensation in the skin. Epileptic activity in the visual cortex can cause visual hallucinations.

During an epileptic seizure, you might be fully or partially conscious, or you could lose consciousness completely.

The specific symptoms experienced by a person with epilepsy can reveal where in the brain the problem lies. This is precisely why Nakken and Tuft believe epilepsy is a kind of window into the brain.

From entire body seizures to lost seconds

“There are two main types of epileptic seizures,” Tuft says, “ones that affect the whole brain and ones that affect only parts of the brain. Seizures that start in one part of the brain may stop, or they can spread to larger parts or the whole brain.

“In generalized tonic-clonic seizures, both hemispheres of the brain are involved in the epileptic activity. This is often the type of seizure that comes to mind when they think of epilepsy: large, terrifying convulsions where the person falls to the ground and loses consciousness.”

But this type of seizure accounts for only a quarter of all epileptic seizures.

Other types can consist of muscles twitching in parts of the body, or sudden inexplicable anxiety and panic, or deja-vu – the feeling of having experienced the same thing before.

Some people have absence seizures, where they just blank out for a few seconds and stare into space and aren’t aware of what is going on.

This can be a big problem for students at school. Parts of the instruction simply disappear. It can take a long time before the adults discover that the child keeps blanking out.

Strange behaviour

Several types of seizures can be difficult to detect. Some people with epilepsy just behave strangely. They might wander around in a daze or sit and fumble with their clothes.

“There are a lot of stories about people behaving strangely or differently, like saying incoherent things or starting to undress in inappropriate situations,” says Tuft.

Some have been arrested for being drunk, or they might be angry and remember nothing afterwards.

Misunderstandings can occur in such cases. Increasing the knowledge about epileptic seizures and how they can lead to all sorts of behaviour could make such episodes easier for individuals with epilepsy.

Sometimes neither the affected person, the family nor the doctor realizes that the patient is suffering from epilepsy. They might think it's a mental health illness.

People who know they have epilepsy can try to inform others about what is happening,” says Tuft.

“In order for others to understand that such behaviours might be due to epilepsy, some people wear a bracelet from the Norwegian Epilepsy Association which shows that they have epilepsy. This is also a measure of security in case a major seizure occurs, so that others understand the connection and can call for emergency help if necessary.

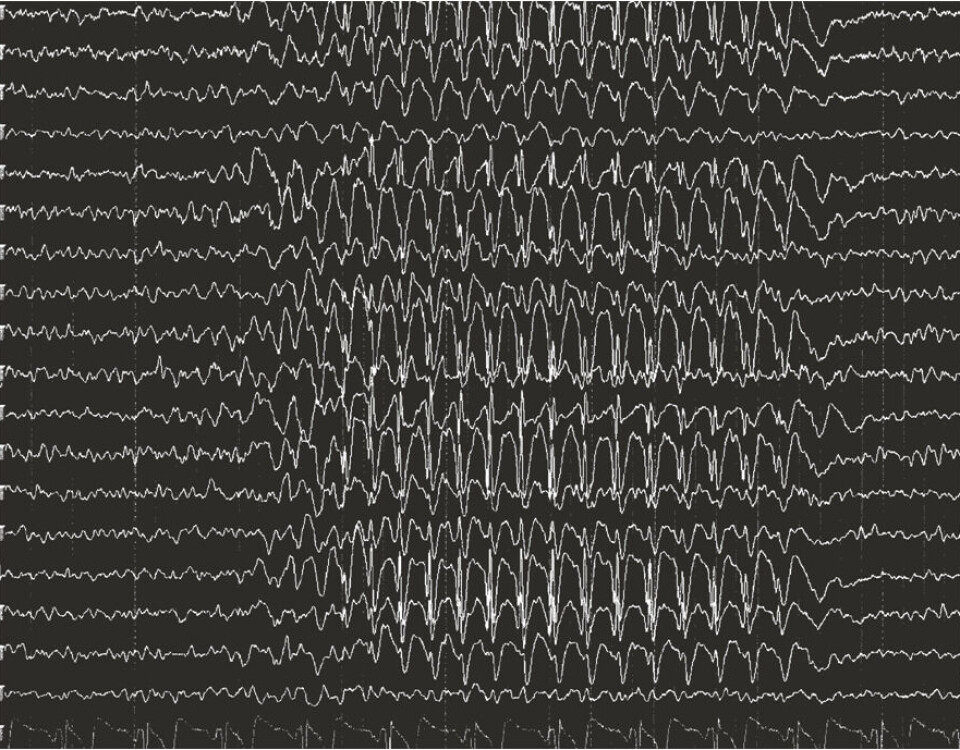

EEG measurements can show abnormal brain activity

At the National Centre for Epilepsy, professionals with extensive experience work with all the strange manifestations of epilepsy. When they admit a patient, they ask the patient and relatives for detailed descriptions of the seizures.

In addition, they can look for electrical disturbances in the brain using a technique called electroencephalography, abbreviated EEG.

Having an EEG involves attaching a bunch of small electrodes to the patient's scalp and recording the electrical activity in the brain.

If the patient has a seizure while the electrodes are attached, the uncontrolled electrical impulses often appear as a characteristic pattern in the lines on the encephalogram: multiple high spikes, followed by a small wave.

Often, the measurements also show abnormal brain activity even when the patient is not having seizures.

Have to consider the whole

A patient with characteristic results on their EEG examination that match the experiences the person has, will often be diagnosed with epilepsy. But it's not always that simple. Brain activity may be normal between seizures.

SSE has a separate department where patients can be monitored by EEG and video around the clock, in the hope of catching a typical seizure early, says Magnhild Kverneland, a researcher at SSE.

In order to provoke seizures during monitoring, the medication is reduced, and the patients are kept awake or exposed to flashing light.

“But epileptic seizures don’t always appear on the EEG. Sometimes they might lie too far inside the brain for the electrodes to pick them up,” she says.

Such situations can be difficult: Does the patient have epilepsy, or is this another type of seizure like a psychologically triggered seizure?

However, assessing the overall picture of the results from all the examinations and the patient's and relatives' own descriptions of the symptoms nevertheless makes it possible to arrive at a correct diagnosis.

The correct diagnosis is very important.

When the correct diagnosis is made, doctors can find a treatment that works. Many people with epilepsy can improve their condition or become completely well with the help of medication, surgery or other forms of treatment.

Everything from genetic diseases to head injuries

Doctors have an easier time coming up with an effective treatment if they can find the cause of a patient’s electrical disturbances.

“Epileptic seizures are a symptom that something is askew in the brain,” says Kverneland.

But this underlying problem can consist of many different factors.

Several genetic diseases can cause epilepsy. But the disorder can also be caused by injuries, such as congenital malformations, brain damage or blood clots in the brain. Just under a fifth of people with epilepsy have a developmental disability.

Damage can also occur in connection with an infection. This is the main reason why the disease affects a larger part of populations in developing countries than in Norway.

Another cause of epilepsy is cancer.

“Brain tumours often make their debut after an epileptic seizure,” says Kverneland.

Even though doctors are aware of many different causes of epileptic seizures, in half of the cases they never find an underlying cause.

Alcohol, stress and menstruation

To make matters even more complicated, it is not just the underlying problems in the brain that determine whether a seizure occurs.

Various internal and external trigger factors also play a role, according to Nakken and Tuft, such as lack of sleep, stress, alcohol and menstruation.

Another factor is anxiety.

“Anxiety is linked to epilepsy, and epilepsy is linked to anxiety, without us knowing exactly why. Seizures in the areas around the amygdala in the middle of the brain can cause a sudden feeling of anxiety,” says Tuft, who published an article on this topic in the Tidsskrift for den norske legeforening (Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association) in 2018.

Many people with epilepsy are naturally also anxious about having seizures in public places.

Treatment and living situation must be adapted to each patient

Effective epilepsy treatment involves more than just medication and other forms of therapy, such as adapting one’s life to avoid the trigger factors that initiate seizures.

Selmer believes the National Centre for Epilepsy plays an important role in arriving at a treatment and living situation that is suitable for each individual patient.

“We have neurologists, psychologists, nutritionists, social workers, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and specialist nurses at the Centre who work together to help the patient,” she says.

Tuft is not part of SSE, but collaborates with them in its work with patients with rare epilepsy-related diagnoses.

She says that many, but not all, patients who have rare epilepsy-related diagnoses also have additional diagnoses such as autism, a developmental disability, ADHD, anxiety or depression.

Then it becomes extremely important for the support staff around such a patient to cooperate and be aware of the connections in the life of each individual.

“An interdisciplinary network is key”, she says.

“I strongly believe in being curious and talking with individual patients. You have to see the patient and next of kin as partners that you can work together with to find the best solutions,” she says.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no