Mercury, bloodletting and animals were weapons in the fight against the shameful epidemic of the 18th century

Sexually transmitted diseases spread through Norway in the 1700s. But was sex their only means of transmission?

“People at that time had a clear notion that immorality was the root of these diseases,” says Susann Holmberg.

She recently earned her doctorate from the University of Oslo, in which she takes a closer look at the epidemic of the time, then called venereal diseases.

Today we understand these primarily as the sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) syphilis and gonorrhoea.

Was prostitution the cause?

There is no good reason why people should suddenly have started having more sex in the 18th century.

So why did the diseases spread in Norway right at this time, including into rural areas?

In countries like England, France and Germany, prostitution and brothels play an important role in the debate about how sexually transmitted diseases spread.

This was not the case in Norway, where prostitution is not specifically mentioned in the sources related to these diseases like it is on the continent, Holmberg says.

Sexual intercourse before and outside of marriage were considered crimes at the time.

“But even though sexual intercourse before and outside of marriage was forbidden, it doesn’t mean that it didn’t occur. We’ve found evidence of this kind of sexual activity in the form of lawsuits related to infidelity and adultery,” she says.

Johanne Corina Bergkvist has explored vagrancy cases from 1790-1802 in depth for her master's degree.

“Drunkeness and noise were the reasons why some brothels were referred to in the sources as notorious houses,” she says.

They appear to be pubs where some young women lived. But prostitution wasn’t being prosecuted, so therefore these places were infrequently mentioned in the interrogations.

“We don’t see the term prostitution used in the sources. This makes it difficult to establish how many brothels there were, the number of women who were prostitutes and the conditions they lived in,” says Bergkvist.

Were the diseases transmitted in non-sexual ways?

One theory as to why the diseases spread is that they were not just sexually transmitted.

They could also have been transmitted by sharing eating utensils or by sharing a bed without having sex, Holmberg says.

We now know that "endemic syphilis," which is still found in poor areas in tropical regions today, causes a disease similar to sexually transmitted syphilis.

Even in the 1700s, a distinction was made between those who had been innocently infected and those who were guilty, the researcher says.

A large survey from 1743 is one of many sources Holmberg has used in her research.

The central administration, which was based in Copenhagen at the time, needed more information to understand this country of Norway in the far north that they were to govern.

A long list of questions was sent to all the priests and bishops in Norway.

Holmberg believes this is a good source as to which diseases were wreaking havoc at the time.

“Rade” disease perceived as an epidemic

Later, around 1770, people became very concerned about another disease in Norway.

The illness was called “rade” disease (radesyken), the Norwegian name for “the wicked disease” and it was considered an epidemic.

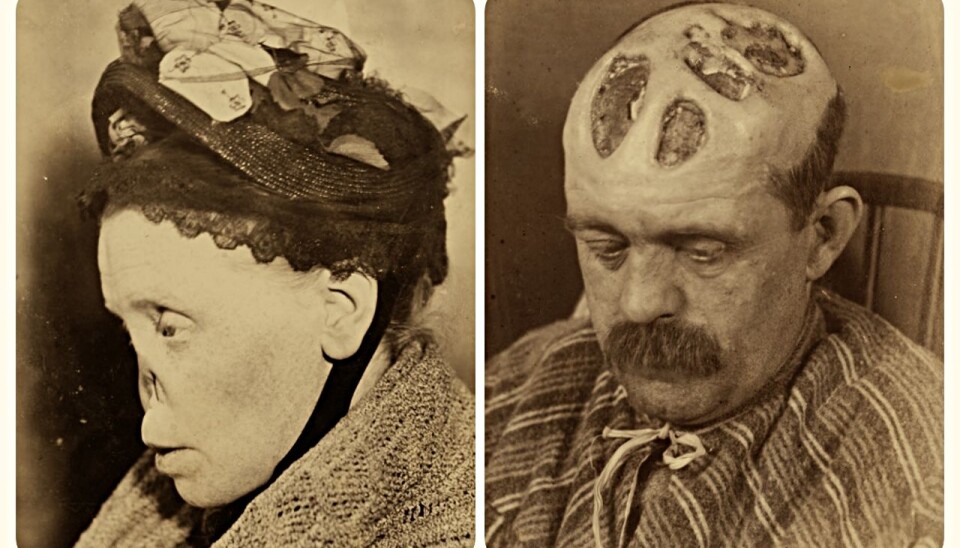

Those who became sick with the disease got deep sores all over their bodies. The result could be sunken noses and obstruction of the throat.

The disease was perceived by many as being sexually transmitted.

Later, in the 19th century, the disease was considered a form of syphilis. Today, researchers believe that they are different diseases.

Not many doctors available

Around 1750, only five official physicians in Norway and a corresponding number of private practitioners had been trained at the University of Copenhagen.

By the late 18th century, the number of university-educated doctors and surgeons was growing.

In the fight against rade disease and sexually transmitted diseases, 16 hospitals were established in Norway for these patients throughout the 18th century, according to Anne Kveim Lie.

She is a physician and received her doctorate on rade disease in 2008.

Much of the treatment was similar

The vast majority of patients received treatment from people other than doctors and surgeons, including priests and pharmacists.

In addition, healers included countless wise-women and self-taught travelling "specialists."

But whether you received treatment from a university-educated doctor or just a folk healer, many elements of the treatment were the same, says Lie.

Mercury was the most prevalent method for treating sexually transmitted diseases. Bloodletting was another common method.

Lie believes there was still a quality difference between the practitioners.

“Educated doctors had learned about many different places on the body for bloodletting and employed several different doses of mercury, whereas folk healers would use the same method for everything.

Did mercury have an effect?

By today's medical perspective, little suggests that the 18th-century treatments would have had an effect, Lie believes.

“But patients continued to return to their practitioners, at least those who were locally known, so they must have found that the treatment worked. We see from the hospital records that numerous patients were discharged as healthy,” she says.

Might that have been because the disease was in a non-symptomatic phase? Or was it because small amounts of mercury actually do have an effect on some STDs? Lie believes it’s difficult to know.

“Mercury treatments – in various forms and doses – were in use until the 1920s in Norway,” she says.

Many missing a nose

In the 18th century, a Danish bishop registered that many patients lacked a nose.

That entry triggered an investigation. Doctors thought the reason was because quacks had wrongly treated patients with mercury.

A law against quackery was enacted in 1794, Holmberg says.

Folk healers could still apply to treat people within a geographically limited area, if they could prove their knowledge. But only a few of them, on the other hand, applied for such a license in Norway.

Many doctors in Holmberg’s sources point out that lots of folk healers were still practicing well into the 19th century.

“And the doctors themselves express that they meet a lot of scepticism from the local population, even though their numbers had grown,” she says.

Great shame

Great shame was associated with these diseases, so going to a stranger with such embarrassing and difficult problems was probably not easy.

Holmberg believes this is one of the reasons why wise-women and other folk healers were used for so long, and why the distrust of doctors was so great.

“Besides, if you think that your disorder comes from something supernatural, then you’d probably go to a person who has a lot of insight into these matters to get treatment,” she says.

Sex with innocents

Folk healers often turned to God when they treated patients.

One piece of advice Holmberg came across was to write a message addressed to God that would be placed on the patient's naked body. God would then remove the disease.

Another idea was that disease could be transmitted from a human to an animal, for example through food, such as bread, which contained the sweat of the sick person.

Holmberg came across a recipe for boiled urine, given to an animal that would then become the recipient of the disease. The urine or sweat would pull the disease away from the patient and into the animal.

She also found a lawsuit from the early 1800s in which a child was sexually abused to cleanse the adult man of illness.

Avoid stigmatizing infected patients

Lie believes that knowledge of past infectious diseases can teach us something about the current COVID-19 situation.

“COVID -19 is transmitted differently than STDs are. But for all infectious diseases, the authorities need to have the trust of the population to be able to prevent infection,” says Lie.

“If the disease means that the patients who get it are condemned by society, it makes it much more difficult to admit to being infected and ask to be tested.”

She believes we have to avoid enemy stereotypes and stigmatizing patients in order to fight an epidemic.

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

———