An article from The National Institute of Nutrition and Seafood Research (NIFES)

Fattening facts behind the 5:2 diet

Study suggests that intermittent fasting is not a gateway to long-lasting weight reduction.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The so-called 5:2 diet, which involves two non-consecutive days of severely reduced food intake a week, is one of the latest fads on the slimming front.

However, research shows that the effects might be of the oppsite of what you wish for.

Experiments on mice

By experimenting on mice that were given a high-fat, sugar-rich diet specifically designed to make them obese, researchers could study how periods of reduced energy intake alternating with periods of free access to food affect fat tissue, and also the gene regulation in fat cells.

They obseverved that intermittent fasting leads to changes in genes that regulate biological rhythms in fat tissue

The study also showed that the expression of genes in our adipose tissue (fat tissue) that regulate the body’s biological rhythms, is disrupted by intermittent fasting.

“We found that mice that were subjected to intermittent fasting put on more weight than those that had free access to the obesity-promoting diet during the entire experiment. There were also lasting changes in gene expression in adipose tissue in these mice,” Even Fjære, researcher at The National Institute of Nutrition and Seafood Research (NIFES) in Norway.

"Clock genes"

The “clock genes”, those that are involved in regulating biological rhythms such as the circadian rhythm, displayed changes of gene expression in their adipose tissue 24 days after the last fasting period.

“This study shows that the development of obesity is not merely due to the total energy intake as such. When we eat and how we divide up our meals are also decisive factors,” says Fjære

The “clock genes” were discovered in the 1990s, since when they have been found to play a central role in regulating the many cyclical processes that take place within cells. These genes maintain order in the internal clockwork by coding both inhibitory and excitatory proteins, which in turn determine how other genes in the cells set their own biological clocks.

Only quite recently has this been linked to energy metabolism.

Twice as much fat in liver

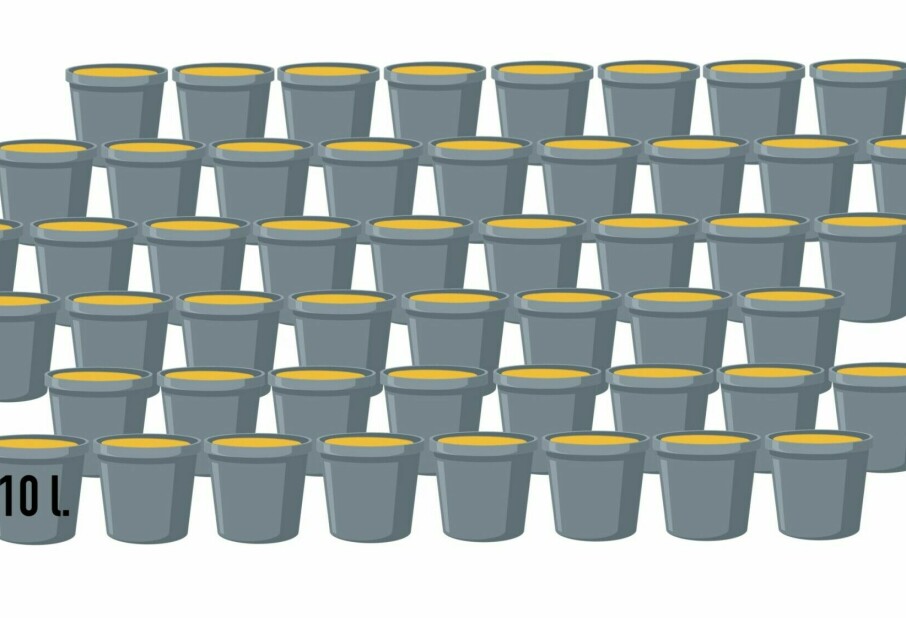

In the experiment, the mice were given a diet that promoted obesity, interspersed with short periods of intermittent fasting.

They were first put on the energy-rich diet for ten days, followed by four days of restricted energy intake, and this cycle was repeated four times in the course of the experiment.

A control group of mice were fed the same energy-rich diet, but without the periods of intermittent fasting.

Somewhat surprisingly, it turned out that at the end of the experiment, the total energy intake was approximately identical in both groups.

Both groups put on weight, but the difference between them was quite clear:

The mice that fasted between bouts of eating had almost twice as much fat in their liver as those who had uninterrupted access to the obesity-promoting diet.

More visceral fat

The intermittent fasting group also put on more visceral fat, which is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

“Working night shifts has previously been shown to increase the risk of obesity and obesity-related diseases, which may be due to changes in the body’s normal biological rhythm," says another resercher behind the study: Simon Dankel from KG Jebsen Centre for Diabetes Research at the University of Bergen.

"Our study suggests that our eating pattern affects the regulation of clock genes in fat tissue, and can make fat cells store more fat per calorie,” Dankel comments.

Warning

Even Fjære emphasises that more research is needed to find out whether weight and clock genes in humans will be affected in the same way as mice on an intermittent fasting regime.

“However, the study sounds a warning in the debate about slimming and intermittent fasting, in particular concerning the popular 5:2 diet, where you reduce your energy intake twice a week to a quarter of daily requirements."

"We may well ask what will happen when the trend ebbs out. It is not unthinkable that this slimming fad will just lead to more obesity and related illnesses, but it is still too early to say,” says Fjære.