Democracies built from top to bottom

Contrary to what many have believed, public participation in forming constitutional laws does not contribute toward more democracy in conflict-ridden countries. Functioning democracies are more likely to be created from above, by the political elite.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Norway has decades of experience in peace and democracy building initiatives round the world.

New constitutions were written in the 1990s in a number of countries emerging from wars, conflicts or authoritarian governments.

It’s been assumed that the transition to democracy would gain if the common citizenry is allowed to be involved in the establishment of a new constitution.

Norwegians have thought that like history played out in their country in 1814, the constitution of conflict stricken countries should be founded in public participation.

Democracy evaluated in 48 countries

They are not alone. Hardly anyone has bothered to test this hypothesis, until the doctoral candidate Abrak Saati at Sweden’s Umeå University has analysed dozens of new democracies.

She made a surprising discovery.

In her work on a doctoral thesis, Saati compared and analysed 48 countries in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Europe.

The public was involved in the formulation of the constitution in many of these nations. The countries where the public was given a large voice were then compared with other countries in the same situation, but where constitutions were hammered out exclusively by the political elite and jurists.

Saati analysed the outcomes.

Her conclusion is that the public’s involvement in writing a constitution is not advantageous for the development of democracy.

Saati found several examples where extensive public participation failed to lead to beneficial democratic developments. But there were many examples where clear democratic progress was made even though the people were denied such empowerment in the formation of a constitution.

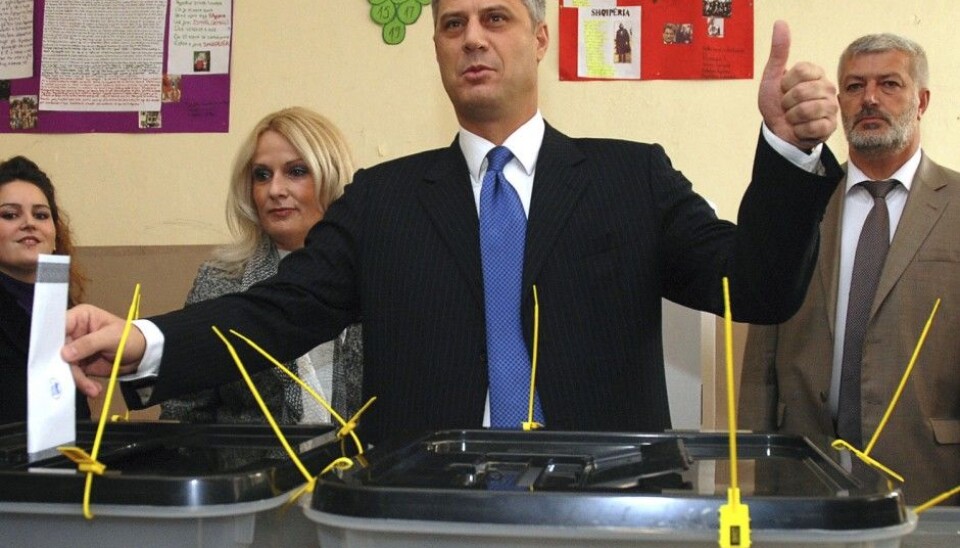

Kosovo and East Timor

“Two examples of the latter are Kosovo and East Timor. Despite the public having hardly any influence on the constitution work, democratic levels have increased. I see the same thing happening in the majority of countries where the constitution was created by the political elite,” says Saati in a press release from Umeå University.

“Meanwhile, democracy has decreased in several of the countries where the citizens had greater influence on the constitutional work.”

Kenya and Zimbabwe

Saati concludes in her dissertation that public participation is not the key factor regarding whether a new constitution in a formerly conflict-ridden country will lead to a successful democracy.

She thinks that politicians’ willingness to cooperate with one another is what tips the scales toward a favourable democratic development.

Abrak Saati has studied two countries in Africa in particular: Kenya and Zimbabwe. The people of both these countries were given the opportunity to participate in the writing of new constitutions. But their developments have gone separate ways.

Politicians in Kenya have a history of cooperating with one another across party lines. New political parties and coalitions have been forged from time to time. Resultantly, many politicians are former colleagues and many are quite well acquainted with one another. Experience and history has taught both old and new Kenyan politicians when cooperation will work and when it won’t.

“This has strongly contributed to a rise in Kenyan democracy levels,” says Saati.

No comparable collaboration across party lines has occurred in Zimbabwe. On the contrary, the ruling party ZANU-PF has held an iron grip on the country since its independence and subjected the opposition to violence and institutionalised harassment. Zimbabwe’s lack of a culture for cooperation among politicians and parties has made levels of democracy nosedive.

-----------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling