You can't jog or eat your way to preventing dementia, researcher says

It’s sad if patients affected by dementia accuse themselves of not having made the right choices in life, says researcher Anders Martin Fjell.

In recent years, we have seen the message everywhere:

You can prevent dementia by changing your lifestyle. The research says so.

When international experts recently reviewed the research in the field, they came up with a list of 14 risk factors that can be addressed. These included high alcohol consumption, smoking, physical inactivity, obesity and low education.

Almost half of dementia cases can actually be prevented or delayed through lifestyle. Most of the risk can also be prevented in mid-life and late in life, the Lancet Commission concluded.

This is fantastic news for anyone who fears dementia. But how sure are we that this is true?

Almost only based on observations

Anders Martin Fjell is critical of the research upon which the reports from the Lancet commission are based.

He is a professor at the University of Oslo (UiO) and studies the human brain and how our cognitive abilities develop during childhood and change during adulthood.

He justifies his criticism by saying that the research is not good enough to say anything about causal relationships.

We can see, for example, that people with low education more often develop dementia. But is it a lack of education that causes dementia?

Similar questions can be asked about many of the other factors: Will exercise in itself prevent dementia? Or do healthier people just have more energy to exercise?

“Almost no studies that form the basis of these reports are suitable to say anything about cause and effect. They are mainly based on observational studies,” he said.

This means that the researchers follow a large group of people over a long period of time. In this way, they can find out that something is connected, but they cannot establish what leads to what.

Fjell himself believes that other factors can be much more important. Factors that cannot necessarily be corrected in adulthood.

Focused on what happens early in life

During the Norwegian Brain Council's annual brain conference last week, Fjell spoke about findings from the research centre Lifespan Changes in Brain and Cognition at UiO.

“Our research indicates that what happens early in life, and not just genetic factors, often has a much greater effect than what happens later in life,” he said.

“As a consequence, it’s not the case that if you had run a little more or eaten a little healthier or solved more crosswords, you could have avoided getting dementia,” he said.

Patients blame themselves

Fjell believes this is an important message for people who have been diagnosed with dementia.

He believes that some patients who are affected by the disease blame themselves for not having made the right choices earlier in life. That’s sad, he says.

“It is primarily important to do things you enjoy. If you absolutely don't like exercising, you don't have to start if you're afraid of getting dementia,” says Fjell.

Most viewed

Differences remain stable

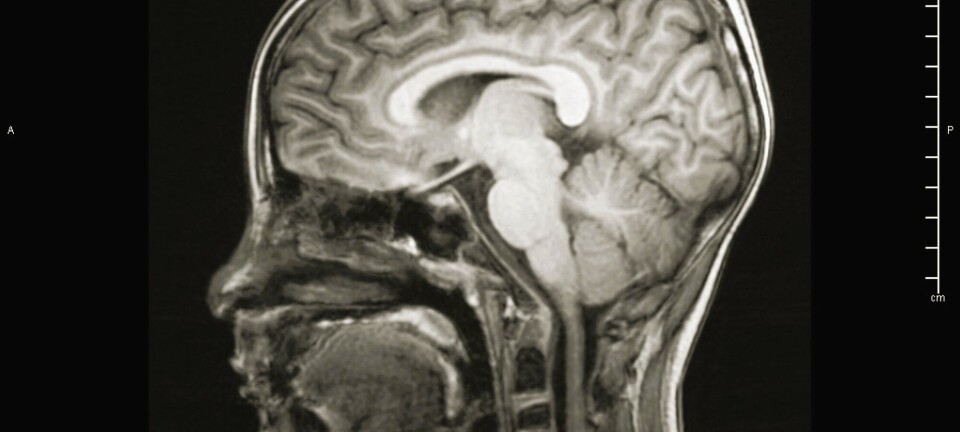

Fjell and his colleagues are trying to understand how the brain develops over our lifespan. They have based their work on research from thousands of MRI images of the brains from roughly 3,000 healthy Norwegian people from 0 to 100 years of age.

The studies show large individual differences between individual brains.

Many of these participants have been followed over a long period. Therefore, the researchers can also see that differences that were detected early in life remain fairly stable throughout life.

“The majority of the differences they see among older people are differences that existed early in life, and not what happened when they were 50 or 60 years old,” says Fjell.

Study from Scotland

Others have also come to the same conclusion.

Scottish researchers studied aptitude tests of eleven-year-olds that were carried out in the 1920s. When they invited the same people in and did similar tests on them as 70-year-olds, they found these surprising results for the first time.

“More than half of the differences in these tests could be explained by their results as eleven-year-olds,” says Fjell.

Birth weight is important

A factor that influences the individual differences in brain structure is birth weight, Fjell says.

“This is partly genetically determined, but also an indication of environmental influences before you are born,” he said.

Low birth weight may indicate that the foetus has been exposed to unfavourable conditions in the womb. This in turn can affect brain development and lead to increased vulnerability, both for mental disorders and dementia later in life.

“But it is important to point out that these are statistical correlations, and not something that determines one's fate,” says Fjell.

“But as a researcher, these are important factors to be aware of, because it shows that conditions very early in life can have consequences for how you function as an elderly person,” he says.

The bigger twin has the bigger brain

Several studies have shown that people with a low birth weight have a higher risk of developing dementia later in life.

“Even identical twins have differences in birth weight, and studies show that the larger twin will have a larger brain area and a lower risk of developing dementia. This cannot be due to genetics,” says Fjell.

Something that can affect birth weight is what happens in the mother's womb.

“If we are exposed to alcohol use, smoking or opioids before we are born, it is much more serious than if we are exposed to this in adulthood,” says Fjell.

Do lower educational levels cause dementia?

The Lancet Commission mentions only one factor early in life that is important for preventing dementia: Education.

Many studies show a connection between education and dementia. The researchers at the University of Oslo have also found this in their studies.

“But this connection almost completely disappears when we control for cognitive abilities at a young age,” says Fjell.

This suggests that it is not low education in itself that is the cause of dementia, Fjell believes.

Perhaps it is rather that people who initially have strong cognitive abilities are more likely to choose to take more education?

Measures to improve cognitive abilities in childhood and youth are probably much more effective than getting people to take more education, he said.

A theoretical puzzle

Bjørn Heine Strand is a senior researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and studies ageing. He believes that when the Lancet Commission concludes that there are 14 risk factors for dementia, the recommendations are based on a theoretical puzzle that has been put together by research.

The commission’s assessment is that the knowledge in these areas is so sound that there is reason to believe that there are causal relationships, he explains.

Some of these connections are almost impossible to determine with randomized, controlled studies, which are the gold standard in research, Strand believes. These are studies where a group of patients is exposed to something and is compared with a group that has not been exposed to the same thing.

It is very difficult to study the risk factors for dementia and obtain a completely watertight knowledge of connections, says Strand.

“You would have to follow the same people throughout their lives. Studies like this are very difficult to design, which is why there are so few of them,” he says.

Hearing and training

Those who have had impaired hearing earlier in life have an increased risk of dementia, according to the Lancet Commission.

“The causal relationship is still unclear, and this has been discussed a great deal,” Strand says.

The same applies to exercise.

Researchers have found strong links between exercise and dementia. Therefore, it is assumed that the more people who exercise, the less dementia there will be in the population.

“But we don't know that for sure. When researchers have done randomized controlled trials, they have not been able to uncover the same connection,” he says.

This was confirmed by Asta Kristine Håberg, a brain researcher at NTNU, to forskning.no in 2023, after they had carried out a large study:

“Physical training is good for the heart, lungs and circulation. It strengthens bone density and muscles, provides better balance, better mobility in joints and increases endurance. This is good for health, especially as we get older. But as of today, it cannot be said that science supports the idea that it results in better scores or less reduction in normal age-related cognitive abilities,” Håberg said.

Those born in 1975 have the highest IQ

The strongest argument that dementia can actually be prevented is that the risk of developing dementia has decreased for each of us over many years.

This can be explained by the fact that the IQ level has increased quite sharply in all industrialized countries over the last few decades. Which again shows that IQ is not fixed and unchanging, but also influenced by environment.

“Higher IQ can be related to better conditions when you are growing up. If this is the cause, we have to expect that this development will not continue,” says Fjell.

Studies from some countries indicate that the trend has already reversed, says Fjell.

“This looks like it has also happened here in Norway. Those born in Norway in 1975 scored the highest on IQ tests. After that the increase has stopped,” he says.

A study of Norwegian conscripts even shows a decline.

Height matters for grip strength

The Tromsø Study is one of the few surveys in Norway that has followed people over a long period.

Bjørn Heine Strand has used the survey to study physical function in the elderly over time. In one study, researchers have shown that Norwegian elderly have significantly improved grip strength. They believe this is a good marker for ageing.

“Much of that can be explained by increased height, which in turn can probably be explained by better conditions in childhood and growing up. This suggests that what happens in the mother's womb and in the first years of childhood are very important for how we get on as adults,” Strand says.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

RELATED CONTENT

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.