Knitting came back, but not hairpin lace. Why?

Some types of needlework disappear, while others become popular again. Have you heard about hairpin lace and the Viking technique of nålebinding?

Liv Klakegg Dahlin guides us into the historical collection at OsloMet’s Department of Art, Design and Drama.

Here, old needlework techniques are stacked in cupboards, drawers, and shelves. We walk past bobbin lace, tatting, macramé, darning, patching, and embroidery. The oldest works are from 1875.

“Here we have hairpin lace,” says Dahlin, pulling out two pairs of mittens and a hat.

Hairpin lace is a needlework technique that is disappearing. It is somewhat similar to crocheting but is done with a hairpin lace loom and a crochet hook. Yarn is laid across the U-shaped tool and crocheted together into strips. Then, they are assembled into garments.

“Hairpin lace creates a denser fabric than crocheting. The garments become a bit stiff,” says Randi Veiteberg Kvellestad, who is an associate professor at the department. There, she has taught the old needlework techniques.

Many of them are dying out. There are too few people who know them.

Weaving lasted for 9,000 years

Weaving is an ancient craft. Archaeologists have found remains of woven textiles in Turkey that are 9,000 years old. In Norway, weaving has been done since the Stone Age, but it became especially common in the Viking Age with the use of looms. These are frames where threads are stretched out, and the yarn is woven back and forth.

Eventually, horizontal looms came along – large wooden looms where people wove tapestries, rag rugs, and clothes. Weaving has remained prevalent up to the present day, though now, there are fewer practitoners of the craft.

The large loom requires a lot of space.

“And it takes time,” says Liv Klakegg Dahlin, who is an art historian specialising in textile arts.

She has moved her loom to her cabin.

“Some needlework is easy to start with, but weaving on large horizontal looms requires equipment and knowledge. Not many people have that anymore,” says Randi Kvellestad.

They knotted their own rugs/tapestries

In the 1960s, it became popular to knot rugs/tapestries. The technique is an imitation of the knots used in Persian rugs, but much simpler, according to The Great Craft Book from 1964 (link in Norwegian).

Additionally, it became possible to purchase ready-made kits that included pre-cut yarn and fabric with a printed pattern. For about a decade, people sat and knotted rugs/tapestries and hung them on the wall.

Then this handicraft trend came to an end. Today, it is still possible to find these rugs/tapestries through online marketplaces and flea markets in Norway.

Severely endangered technique

Filet lace is another technique that is severely endangered.

First, a net was made, similar to a fishing net. Then, some of the squares in the net were filled with embroidery to create a pattern.

But not all needlework techniques disappear. Some persist through time, while others might fade only to resurface later.

Knitting: A craft for everyone

Knitting arrived in Norway in the 17th century, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian). Women knitted garments for the family or for sale. Four decades ago, knitting was a common pastime among women of every age (link in Norwegian). However, interest waned over time, and about 15 years ago, knitting seemed to be an activity mostly preserved by the older generation, according to Statistics Norway. Then something happened.

Knitting experienced a revival.

Now, three per cent of men and nearly half of the women across all age groups knit. Crocheting has also seen a similar increase in popularity.

Nålebinding is also a technique that has experienced a revival, but for a very special reason.

The Vikings practiced it. And many are fascinated by them.

Repairing, sewing, and altering clothes have become common again. In the past, these were essential skills.

Invisible work

OsloMet’s Department of Art, Design and Drama has a past in Den kvindelige industriskole i Christiania (Women's School of Craft and Industry Christiania). From 1875, they offered three-month courses for young, unmarried women who wanted to become teachers, work in a fabric store, or start their own business.

The women did not have much time. The courses were short because they were expected to enter the workforce immediately.

Kvellestad showcases works left behind by the first students.

“I’m incredibly impressed by how they learned to darn and patch The fabric seems seamlessly joined; it's nearly invisible. Everything was done with great care,” she says.

“Stopping, patching, and mending clothes has surged back into popularity. Redesign is popular,” says Kvellestad.

Neither Dahlin nor Kvellestad can pinpoint exactly why some old needlework techniques are making a comeback.

Treasures from grandma

They see that their students are focused on sustainability and reuse.

“It seems to cycle through generations. Clearing out grandma's wardrobe after she's gone, you discover items you find appealing. Handcrafts are revived, often skipping a generation. We might not adopt our mothers' fashion, but our daughters will," says Dahlin.

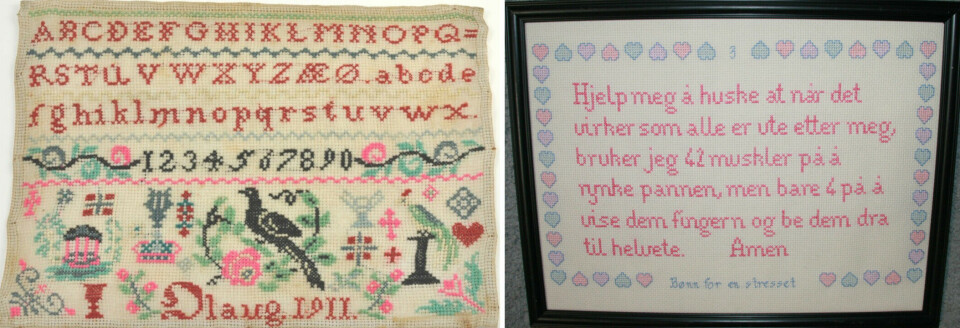

Embroidery dates back to the Stone Age, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia. It has also been an important activity for women in more recent times. With needle and thread, women decorated garments, pillows, beddings, and created pictures.

Some were for everyday use, while other embroideries were for decoration.

“Women were encouraged to embroider because it was seen as a way to learn frugality and patience. They were supposed to sit and behave properly. It’s not surprising that there was a rebellion against this,” says Dahlin.

In 2010, guerilla embroidery emerged/a more contemporary and liberal form of embroidery emerged, breaking with both the diligence and traditional motifs. Now, needle and thread were used to express humour, anger, and defiance.

Teachers lack expertise

Liv Klagegg Dahlin believes that forgotten needlework techniques will make a comeback.

“They are not extinct because there are always some people who are still practicing them,” she says.

The department she leads educates teachers in design, art, and crafts.

“We try to reach all primary schools in Norway by educating teachers who have expertise in these techniques,” she says.

Children are supposed to learn handicrafts during arts and crafts classes at Norwegian schools.

“But principals don’t hire teachers with expertise in needlework. What we teach our students here is missing in Norwegian schools,” says Dahlin.

According to Statistics Norway, half of those who teach arts and crafts have no expertise in the subject.

“The situation continues to deteriorate, which explains why these crafts are disappearing,” she says.

The government is committed to incorporating more aesthetic and practical subjects into schools, according to a press release from this year (link in Norwegian).

“But how are they going to achieve that when the expertise is lacking? I myself experienced that my children were sent home with two needles and a ball of yarn because the teacher couldn’t knit,” says Dahlin.

Endangered handicrafts

It’s not just OsloMet and other teacher training programmes in arts and crafts that are keeping old handicraft techniques alive.

“The craft associations are doing a tremendous job,” says Dahlin.

The Norwegian Folk Art and Craft Association has created a Red List for traditional craft techniques at risk of being forgotten.

Techniques such as hairpin lace, filet lace, and nålebinding are on the list.

Local craft associations have taken responsibility for various techniques. They document, offer courses, and keep the knowledge alive, according to husflid.no. There are now bout 100 endangered techniques on the list, with more being added.

Dahlin believes handicrafts give us a sense of accomplishment.

“And tranquility. It's good for us to sit down, focus, and work with materials. Humans have been doing this for all eternity. We need hands-on activities, beyond just digital interaction or cognitive tasks,” she says. “The act of sitting still and concentrating is not valued in the way it used to be.”

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no