Why did some of the indigenous Sami people revolt in 1852? Two of the rebels tell their stories in a new book.

The Sami were subjected to abuse of power and violence long before the Kautokeino uprising, in which both the sheriff and the local merchant were killed.

"The bailiff then said to me, ‘The bailiff’s acquaintance will now take a dram.’ (...) Then the bailiff said to me: ‘Now the bailiff's acquaintance will start dancing with the girl, so he can be of good courage tomorrow when he is going to drive!’"

On the journey across the wild and mighty Finnmark Plateau in northern Norway one evening in the 19th century, the tax collector poured liquor, insisted on dancing even though no one wanted to, and thrashed the driver the following day when a reindeer that was to pull the sled had disappeared.

Examples of demeaning behaviour by the Norwegian authorities towards the indigenous Sami people abound in the accounts of Anders Pedersen Bær.

After each day's work as a prisoner at Akershus Fortress in Oslo, the reindeer herder would write about everything from his childhood and everyday life to encounters with the authorities.

The sami people have inhabited the northern arctic regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Russian Kola Peninsula for 3500 years. For centuries they were abused and discriminated against, and Norway has been criticized internationally for their politics of ‘Norwegianization’ of the sami in Norway. This was discontinued in the 1980s.

At the time of the Kautokeino rebellion in 1852, these politics had not yet come into force officially speaking. Their roots however stem from missionary programmes from the 1700s, and the sami were marginalized and discriminated against throughout the 19th century, as the accounts of Anders Pedersen Bær and fellow prisoner Lars Jacobsen Hætta bear witness to.

Bær was convicted for participating in the Kautokeino rebellion on 8th November 1852, and subsequently spent a decade in prison. Hætta was originally sentenced to death for his partaking in the rebellion, but this was later changed to life in prison. He was pardoned in 1867.

Now the manuscripts that the two sami men left behind have been compiled in a new book.

Incredible glimpse into the times

Their stories give rare insights into 19th century Sami communities.

The writings “open an absolutely incredible window into the times,” says Ivar Bjørklund, a professor at UiT Norway's Arctic University.

The stories have been published before, but have been relatively unknown to a larger audience, according to Bjørklund.

Together with colleagues from the Sámi University of Applied Sciences in Kautokeino, he presents the manuscripts both in Northern Sami and in a new Norwegian translation. The new book also includes three chapters of the researchers' interpretations of the stories from Bær and Hætta.

Provoked by the authorities

Norwegians and Sami who did not speak the same language were like two types of herds that could never become one, as Bær describes it. They did not understand each other linguistically or culturally.

The Sami view of life – the moral universe, as Bjørklund calls it – often provoked the Norwegian authorities.

And the authorities provoked the Sami even more.

During the Kautokeino uprising in 1852, a number of Sami attacked the Kautokeino authorities and residents. The sheriff and a merchant were killed. The priest was beaten and several other people were mistreated.

“You can understand why the Sami acted as they did. They experienced such a double standard from priests and officials, and the attitude towards everything Sami was condescending,” says Bjørklund.

Others believe the rebels were religious fanatics. There are mixed opinions about how justified the rebellion was, according to a 2013 NRK article (in Norwegian).

Drunken priest on a sled

Like many others at that time, Hætta and Bær became part of the Christian Laestadian revival movement.

The movement identified alcohol as a great sin in a society that was severely affected by alcohol abuse.

Even the men of the church were far from pious.

Bær tells of a time when he shuttled a priest to Alta.

"The priest was so drunk that he could hardly stay on the sled. As we approached Biggejávri, he repeatedly shouted that I should stop and come and help him, because he had rolled out of the sled onto one elbow, so that he was hanging onto the edge of the sled with one hand, and was holding himself up on his other hand and elbow, and was getting dragged off with that elbow underneath him."

Beaten at school

Bær thought he learned a lot through the revival movement.

It was a big contrast to his previous confirmation instruction.

Priest Nils Joachim Christian Vibe Stockfleth was a supporter of conveying Christian teachings to the Sami in their own language, but at the same time showed little understanding of the fact that many Sami were illiterate.

"I tried to spell, but it didn't turn into a whole word, because I didn’t know how to spell. Then the priest took the New Testament from me and struck me under the ear, and went from child to child and struck them under the ear," Bær writes, noting:

"The little bit of love we had for priest Stockfleth cooled dramatically."

When the revolt erupted many years later, the violent priest was not the right man to calm people’s tempers.

Religious conflict

Religious, social, economic and personal issues all contributed to the Kautokeino rebellion, according to the Store Norske Leksikon (Big Norwegian Lexicon).

Conflicts had built up over time.

The Church of Norway did not like the revival movement, and punished followers for disrupting services. "The awakened," for their part, believed that the priests were "soul killers."

Authorities further diminished Sami trust by confiscating their animals to pay off debts and blocking their seasonal nomadic routes, jeopardizing the Sami livelihood of reindeer herding.

Each winter, the Sami drove the reindeer to Finland to graze. In the fall before the uprising, the Russian tsar decided to close the border so they couldn’t cross over.

Rebellion not mentioned

Even the Sami who hadn’t converted to Laestadianism weren’t spared the anger of the rebels. The rebellion was in fact stopped by Sami people who were not on the side of the "awakened" rebels.

In the court hearings following the uprising, the participants did not mince their words. The church and state were described as "the devil's work," according to interrogation records.

However, Bær and his co-conspirator Lars Hætta made no mention of the rebellion when writing about their lives in prison. Bær’s text stops four years earlier.

It’s possible he didn’t get any farther before he was released in 1863. Or maybe he restrained himself.

Probably censored

Bjørklund surmises that the text was read and perhaps censored by Jens Andreas Friis, a linguist who taught the two Sami to write in prison and preserved their stories.

“I think it was because Friis was working on applying for a pardon for the two men. I think it wouldn’t have strengthened Bær's application if he’d written about the insurgency as he experienced it,” says the researcher.

Although Bær has his ideas about the treatment he is subjected to, the text is not very political.

But Bjørklund sees the seeds of an uprising in the descriptions of the many unpleasant meetings with government officials.

"There’s a lot to read between the lines here," he says.

Intellectual convict

Whereas Bær described his life, Hætta wrote mostly about religion and morality.

He described Sami "shouters", who would shout out messages of doomsday. Hætta also wrote about the faith of the Sami before Christianity.

“Hætta was obviously the intellectual of the two,” says Bjørklund.

Lars Hætta was only 18 years old at the time of the uprising. It is unclear when and where he wrote what, but it is certain that he continued after his 15 years in prison. He describes events that happened long afterwards.

Hætta translated the Old Testament into Sami and helped the researcher Friis with his knowledge of Sami culture.

Sinful Sami

Bjørklund thinks Hætta’s views on spirituality in Kautokeino are among the most interesting parts of the manuscripts.

The converts weren’t just angry at the authorities. They also wanted to clean up their own ranks.

Hætta summarizes the most common sins of his fellow villagers:

"To sum it up: drunkenness, theft, lewdness, crude and shameless talk, whining, strife, swearing, love of worldly things, desire for money and goods, and greed that makes them complain and whine about too much food and meat being eaten.”

Family conflicts

Family was important among the Sami. Bær vividly describes family relationships, gender roles – and the conflicts with his father.

Father and son were prosperous, with a total of 600 reindeer. The father did not accept the marriage of his son to the less well-off Inger Jacobsdatter Hætta, and he wasn’t happy that the family had to feed her younger brother on top of it. The father goes after the brother several times in a drunken fury.

Bær eventually had enough and wanted to separate his reindeer from the family flock to establish himself on his own. But his father refused. Eventually, the son disentangled himself, but his father kept some of his reindeer.

Yet Bær still feels sad when his father is on his deathbed.

"When I had gone about half a dog's howl away from my father's lavvu, sadness touched my heart as I thought of my father, that now I had spoken to him for the last time. I went and cried."

“This is pure movie script!” Bjørklund says.

The actual film about the Kautokeino rebellion came in 2008. Director Nils Gaup knew of the two prisoners’ writings, according to an interview with ABC News (in Norwegian).

Developed written language for Northern Sami

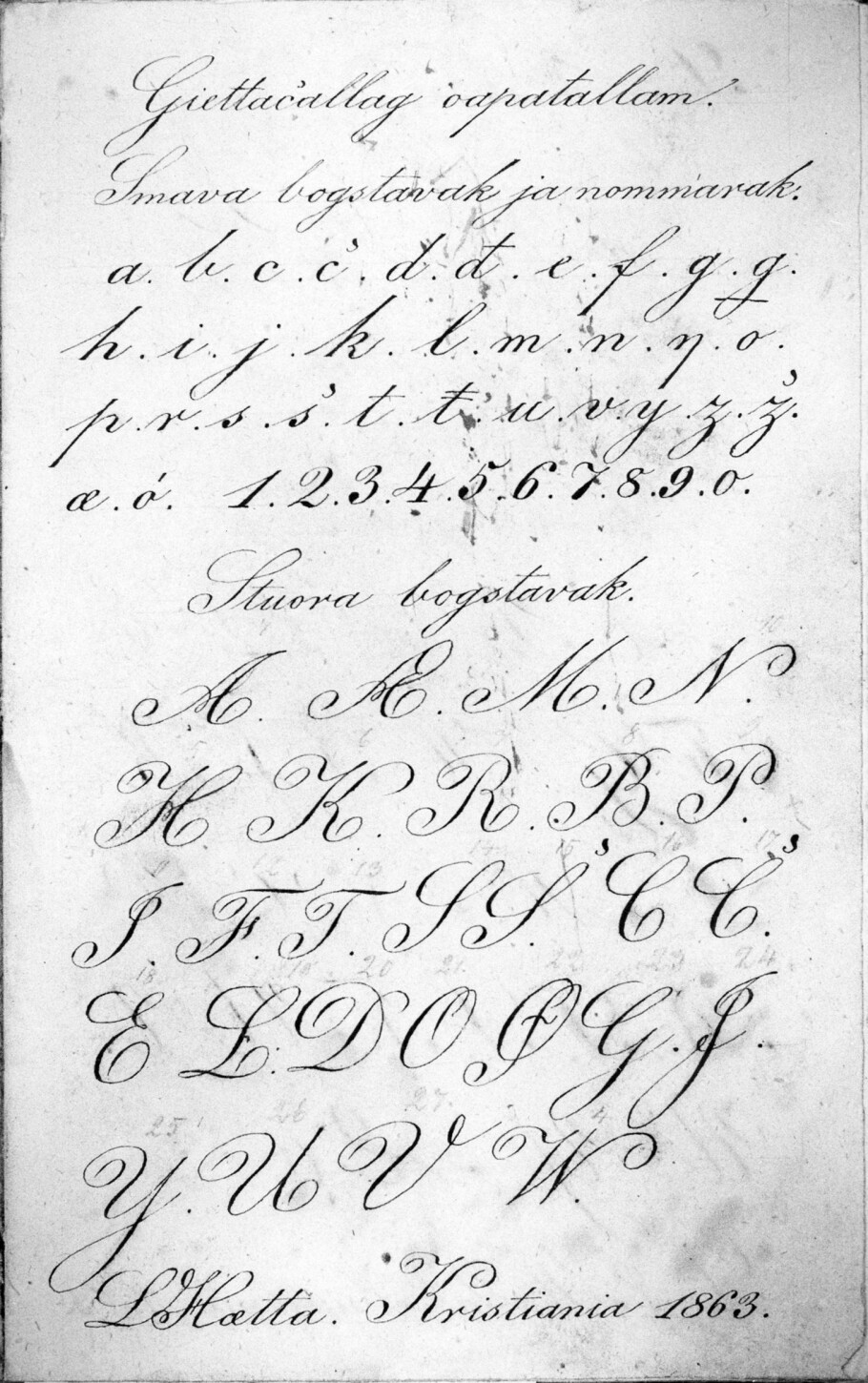

The manuscripts by Bær and Hætta were also a linguistic experiment.

They are the earliest sources in the Northern Sami language written by Sami that researchers know of.

Friis wanted to create a Sami written language. He was assisted by the two prisoners in completing the very first standard Sami orthography.

“This was an impressive research project that took place in those prison cells. They created a written language while sitting there as criminals,” Bjørklund says.

Reference:

Nils Oskal, Johanna Johansen Ijäs and Ivar Bjørklund (eds.): Lars Hætta and Anders Bær. Erindringer – samiske beretninger om Kautokeino-opprørets bakgrunn, etikk og moral. (Memories – Sami accounts of the background, ethics and morals of the Kautokeino rebellion. Orkana Akademisk forlag, 2019.

———