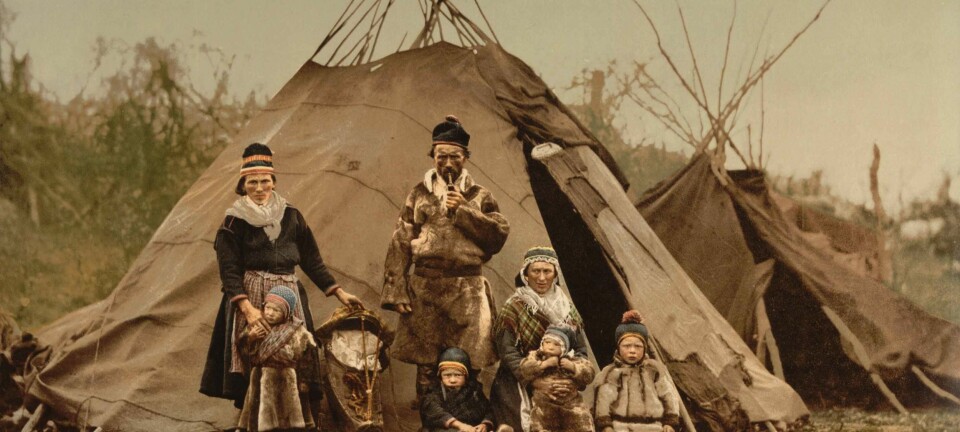

The Sámi in Norway have more influence on politics than the Swedish Sámi

The Norwegian Sámi Parliament has both more influence and independence than its Swedish equivalent

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Norway and Sweden have very similar political systems, yet these two countries chose to create two very different approaches to provide their indigenous Sámi populations political representation.

These differences have given the Norwegian Sámi Parliament a number of advantages over its eastern neighbour, researchers say in a newly published article in the international journal Ethnopolitics.

More rights in Norway

There are several reasons why the Norwegian Sámi Parliament appears to be more influential than its Swedish counterpart, says researcher Jo Saglie at the Institute for Social Research in Oslo.

He says the Norwegian Sámi Parliament can decide which issues it will take up, a right that is enshrined in Norwegian law on the Sámi people. In contrast, the Swedish Sámi Parliament is more limited in the issues it can address.

National political parties involved

When it comes time to elect the 39 representatives to the Norwegian Sámi Parliament, both Sámi parties and national political parties offer candidates.

In Sweden, only Sámi political parties offer candidates for election. This reflects the fact that the Norwegian Sámi have closer ties to the national political system than the Swedish Sámi, Saglie says.

The closer ties may give Norwegian Sámi an advantage, he says, in that they have better access to the Norwegian political system.

Connection important

The connection between the Norwegian Sámi Parliament and the national political parties means that the Sámi can get the national parties to take up local and national issues, Saglie says.

“This even includes the Progress Party, which wants to abolish the Sámi Parliament, but which nevertheless has had representatives elected to the Sámi Parliament,” he said.

Stronger international obligations

Another factor that makes Norway’s Sámi Parliament stronger is that Norway has a stronger commitment to international obligations than Sweden, the researcher says.

For example, Norway has signed the 1989 International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, which says that indigenous people shall be heard on matters that affect them. Sweden has not signed this convention.

“The Norwegian Sámi have been able to use this as a pressure tactic, which has made it easier for them to succeed,” Saglie said.

The researchers cite the success of the Finnmark Act of 2005, which relates to the management of natural resources in Norway’s northernmost county, Finnmark. The Act handed over land formerly owned by the Norwegian government to a newly created body called the Finnmark Estate. One reason for the passage of the law, the researchers wrote, was that the Norwegian government was uncertain as to its legal claim to the land under international law.

The Act requires that the land be managed “for the benefit of the residents of the county and particularly as a basis for Sámi culture, reindeer husbandry, use of non-cultivated areas, commercial activity and social life.” The board of the Finnmark Estate is appointed by the Norwegian Sámi Parliament and the Finnmark County Council.

Swedish Sámi Parliament split

The Swedish Sámi Parliament is more subject to the Swedish government, and is almost like a directorate, Saglie says. That makes it is difficult to reconcile its two different roles, as both an elected representative body and a government agency, he says.

The Swedish Sámi Parliament is also split down the middle, with a strong conflict between reindeer herders and other Sámi, he explains.

This has historical roots. The Swedish state made a distinction early on between herders and other Sámi, which has helped to create a rift that is still found in the Swedish Sámi Parliament today.

The Alta affair

The researchers also believe that a battle in Norway over the damming of the Alta/Kautokeino River in the 1970s and early1980s “put Sámi rights on the national political agenda in an unprecedented way.” The initial plans called for flooding a Sámi village as well as a substantial area used for reindeer grazing.

The Norwegian Sámi staged hunger strikes in Oslo, and Sámi women occupied the prime minister’s office. Their opposition was also supported by Norwegian environmentalists and local people, who feared that the development would harm the river system’s wild salmon population.

Although the dam was ultimately built, the researchers believe that this highly visible conflict mobilized the Sámi people in Norway, and also made Norwegian politicians feel guilty, and committed to rectifying injustices against the Sámi people.

The Sámi Act, which created the Norwegian Sámi Parliament, was passed by the Norwegian Storting in June 1987 and the Sámi Parliament convened its first session in October 1989.

——————————-

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no