Could we predict crimes the way we predict weather?

Experts think we have enough data to be able to know where the next crime will happen before it actually does. But criminologists say that’s pure hype.

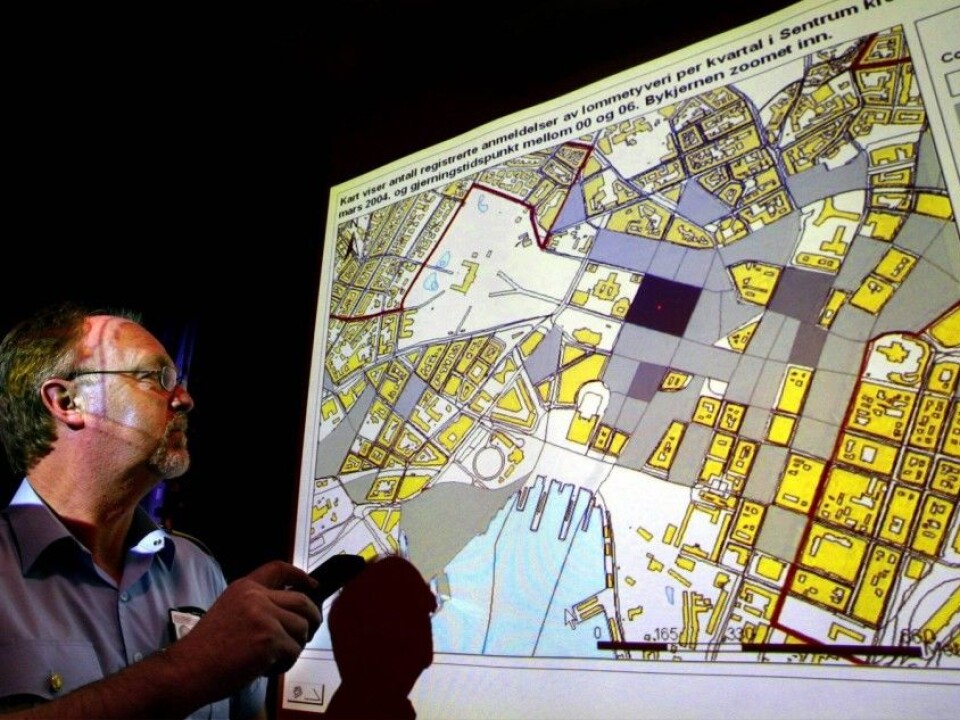

In this data-driven world, it should come as no surprise that criminologists have spent the last few decades collecting data on the details of where and when crimes happen.

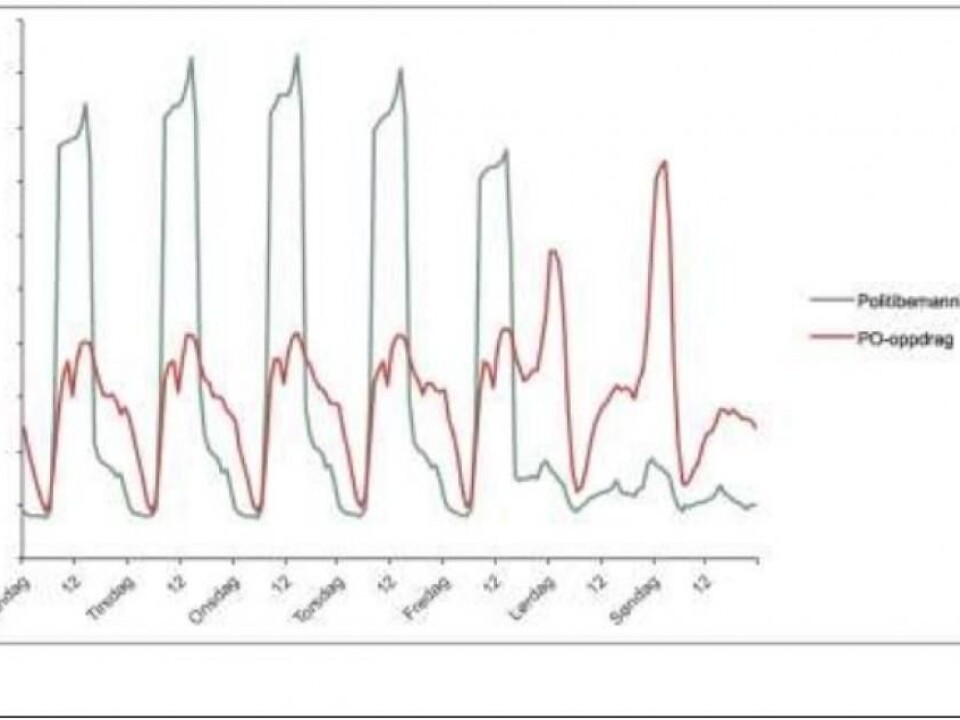

The design of street networks, lighting, where victims and criminals go, escape routes and time of day may all help explain why burglary, robbery and theft tend to happen in certain locations, and at certain times.

Even the weather and whether or not it is payday can affect these patterns.

All these factors have been folded into sophisticated computer programs, or algorithms, which can suggest when and where crime is likely to occur—before it actually happens.

Predict and prevent crime

The use of these algorithms in this situation is called predictive policing. Some variation of this approach is already in use in a variety of cities across the globe, including Zurich, London, Chicago and in different cities in California, among other locations. The Norwegian Board of Technology has recently recommended that the Norwegian police adopt the approach.

The idea is that predictive policing can help the police do a better job of organizing patrols to prevent crime, such as by locating more visible police units and street lights in specific risk areas.

“A potential criminal is always weighing the trade-offs: How big is the chance of being caught and what kinds of possibilities are there to get away? Basically, it’s a matter of how unsafe it is for the perpetrator,” says Robindra Prabhu, who is head of the Technology Board’s projects on big data and policing.

From operations centre to tablets and phones

In Norway, the debate about the use of big data analysis by the police has only just begun.

In the United States, and to some extent in the UK, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, the approach has become more and more common.

In Santa Cruz, California, for example, the police have started using software called PredPol, which is based on the assumption that certain crimes will happen within a certain radius of earlier crimes.

A map in the police operations centre allows managers to monitor potential risk areas, which are highlighted as small red boxes, while patrols out on the street can do the same via a tablet or mobile phone.

According to the company that sells PredPol, the new software has caused crime rates to decline by as much as 13 per cent in Los Angeles and by 27 per cent in Santa Cruz.

Little research

In spite of these positive results, there has been relatively little independent research on predictive policing.

Professor Inger Marie Sunde at the Norwegian Police University College believes it is nevertheless prudent to initiate pilot projects in Norway, provided that they do not involve monitoring individuals.

She also believes that pilot projects would offer Norway a good opportunity to collect more systematic and independent information on predictive policing.

“The Norwegian Board of Technology believes predictive policing offers a promising opportunity for more effective and preventive efforts,” says Sunde.

What about the 22 July terrorist attack?

The commission that looked into the attacks by Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 people on 22 July 2011, emphatically stated that the Norwegian police must join the technology revolution.

Although Sunde acknowledges that hindsight is always 20/20, she said she believed that computer tools would have allowed police to prevent Breivik from acting at a number of occasions.

“For example, big data analysis could have picked up the order for the bomb directly from open Internet sources,” she said.

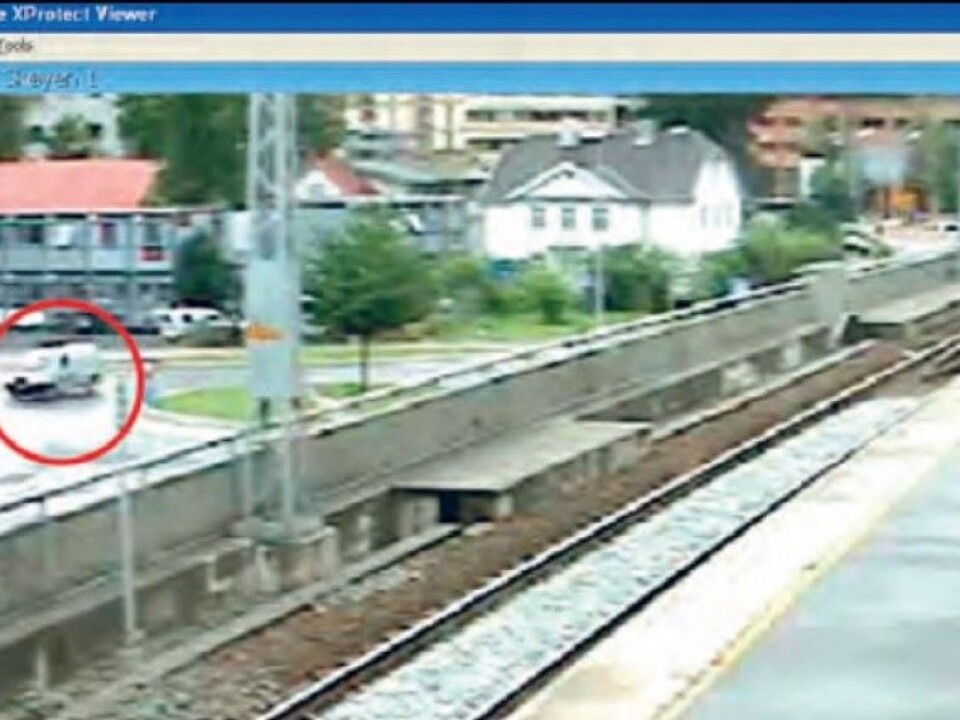

The police could have also addressed the stream of tips that came from the public via smartphones.

The tips could have been combined with other information, such as data from surveillance cameras, and with information that was only available in paper form at the time, such as a sticky note with the terrorist's car registration number.

“This is a form of real-time analysis that the police are still unable to do,” she said.

Controlled by commercial interests

Heidi Mork Lomell is head of the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law at the University of Oslo, and has conducted extensive research on surveillance.

She believes that predictive policing is just a new name for something the police have been doing for years, but that is driven by commercial operators who are eager for police to buy their software.

Lomell believe a promotional video from IBM illustrates her point:

“This is hype,” says Lomell.

“What is new is that they are promising more than before—namely, that knowing crime patterns will allow crimes to be predicted, and the police will thus be able to nip crime in the bud,” she said.

She believes the method is limited because it is not possible to predict exactly how and when a crime will be committed, and that the benefits of the software are probably less than the commercial companies claim.

“I am also sceptical about what measures the police will use to stop crimes before they have happened. There is still too little focus on this, along with potential counterproductive effects, ethical issues and legal challenges,” she says.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no