Your genes, not your blood type, are important in determining how you’ll respond to a COVID-19 infection

Ten minutes. That’s how long it took for a Norwegian billionaire to decide to fund a major international study on COVID-19. Now the research results are rolling in.

When the coronavirus hit Europe in March, many Norwegian medical researchers had to work from home offices. This also gave some of them more time to do research.

And it gave Tom Hemming Karlsen, a professor at the Department of Clinical Medicine at the University of Oslo (UiO), and his colleagues, an idea.

“While our colleagues in Italy and Spain were treating so many COVID-19 patients that they fought life-or-death struggles in beds stuck in hospital corridors, we had extra capacity. So we wanted to start a project to answer the big question many of us have pondered: What’s so special about this disease?” he said.

Something they had never seen before

A number of researchers and specialists have found that COVID-19 patients became ill in a way they had never seen before.

“People who had been at home one night watching TV might find themselves on a respirator in the intensive care unit just few hours later. The course of the disease was very different from anything we had seen before,” he said.

In collaboration with German colleagues, the Norwegian researchers decided to start a big research project. They wanted to get to the bottom of the question.

Karlsen and his colleagues contacted a network of researchers they knew in Italy and Spain and asked about obtaining patient data.

It had to happen fast

But research requires money. The most natural thing would be to write an application to the Research Council of Norway and ask for funding. But it would take too long to get an answer. And the answer would not necessarily be “yes”.

That’s when the researchers had another idea.

They contacted the Norwegian businessman and billionaire Stein Erik Hagen, who has supported previous medical research projects. They simply asked him if he could give them money for the study.

“It took about ten minutes before we got a ‘yes’. That’s the fastest research grant we have ever gotten,” Karlsen said.

It also meant that the researchers could throw themselves into the project right away.

Mapping genes

Help came from almost 100 local doctors in Italy and Spain. They quickly recruited almost 2,000 patients with severe COVID-19.

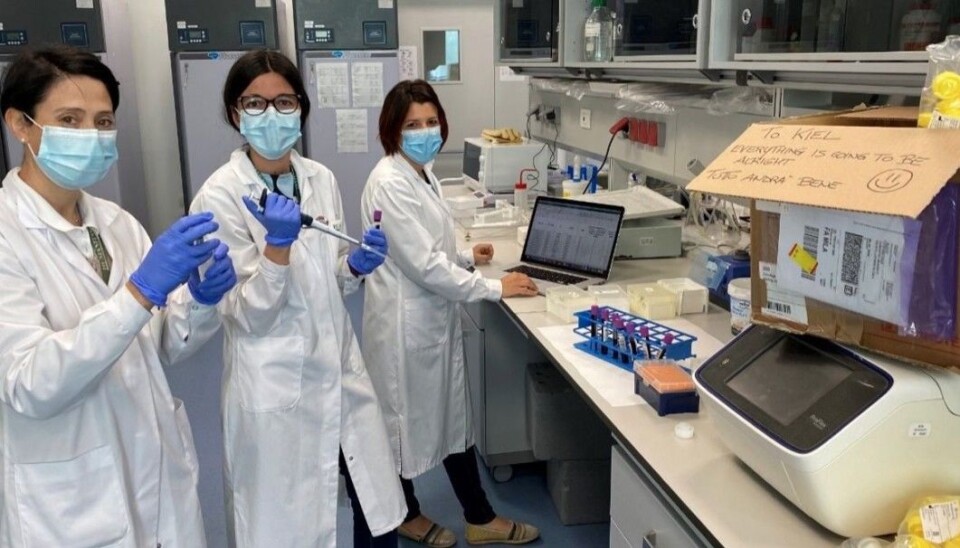

The samples were sent to Norway and Germany to be analysed. Here, the researchers have now documented gene variations in these patients and compared them with genes in the general population.

Less than three months after the study began on March 12, the first scientific article was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The research and analysis behind publishing a research article like this usually takes years.

“Everyone was so giving. In Kiel, where they did the genetic analyses, the technicians worked for free during the evenings and did double shifts,” Karlsen said.

Karlsen said that working with the project has been very inspiring.

“There has been a spirit of cooperation and an openness in research that I have never seen before. Everyone has been much more concerned with getting the information out rather than getting personal recognition, which often means a lot in research,” he said.

Supported their suspicions

When they finally got the results of the analysis, Karlsen and his colleagues’ suspicions were confirmed.

“Biologically, this disease looked really completely different than anything else we have seen before,” he said.

The researchers were the first to discover the genes that are behind the serious lung disease COVID-19 patients get.

If you have these genes, you have twice the risk of becoming seriously ill from COVID-19.

“In numerical terms it doesn’t sound so impressive. But in a genetic sense, the difference is very big. Often, genetic risk factors are much weaker,” says Karlsen.

Neanderthal genes

This is an exciting area in genomics, he explains.

“These genes were originally found in the Neanderthals and they subsequently have spread to various living population groups,” Karlsen said.

The researchers weren’t surprised to find this genes, however.

“We had expected to find some genetic factor that makes some people much sicker than others,” Trine Folseraas from Oslo University Hospital said this summer to the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, NRK. She is part of the Norwegian-lead group that got the results.

Four new risk-related genes

Now there are even more results.

Last week, British researchers published a study in the journal Nature. Their study, which relies on even more patient data, identified four new genes that are important in determining if a person will become seriously ill with the coronavirus.

“These four genes are a little harder to interpret. They have something to do with the immune system and with our defence against viruses. One of them is known for being related to severe lung disease, but the others have not been linked to diseases before,” Karlsen said.

These new genes are a little weaker in terms of risk than the Neanderthal genes, but there’s a clear relationship between the genes and an elevated to risk is completely certain, Karlsen said.

Better treatments in the future

Karlsen believes that the COVID-19 risk genes that have now been identified are interesting for further research.

“Before we can begin with new patient treatments, we have to understand what happens in the body when they become seriously ill,” he said.

Basically, what happens in severe COVID-19 disease is an overreaction from the immune system, a kind of severe inflammatory reaction. Once researchers know which parts of the immune system are responding, they can create immunosuppressive drugs that are more targeted and have a better effect.

Today, cortisone is often used to alleviate inflammation, even in severe COVID-19.

“This is a broad-spectrum medicine that works everywhere in the body. It's like shooting sparrows with a cannon, it would be better to be able to use something that’s more targeted,” Karlsen said.

He’s optimistic and believes that a lot will happen in terms of treatment as early as 2021.

“The research is going very fast now. We wanted to get the data out quickly so that other researchers could get started and work with them. Now the articles are starting to come. I am optimistic and believe that 2021 will give us many fruits from the findings we have made in 2020,” he says.

Blood type less important

Another finding that Karlsen and colleagues uncovered during their study was that if a person has blood type O, that person will have a little extra protection against being infected with the coronavirus.

Those with blood type A have a slightly higher risk.

Blood type thus seems to have something to do with how easily a person gets infected. But the blood type does not affect how severely the disease affects you, says Karlsen.

“This may have something to do with the way the virus enters the body. There are surface molecules that bind the virus differently, depending on your blood type,” he said.

But blood type doesn’t make such a big different for most people, he said.

“The difference between people who have blood type A and O is very small. When it comes to infection, there are two things that apply, one is social distancing and the other will be the vaccine. Blood type is more of a biological curiosity,” he said.

Blood type does not explain differences in infection

More than half of all Norwegians Norway have blood type A. But the blood types in the world vary greatly. In general, about half of all people in the world have blood type O.

Different blood types do not explain why the infection is spreading differently across the globe, Karlsen believes.

“But differences in our genes can explain that,” he says.

No Neanderthal gene in China

The Neanderthal gene is found in varying frequencies around the world. While about 10 percent of the Norwegian population carries the gene, it’s not found at all in China, Karlsen said.

“There’s a very high prevalence of this gene in India. Combined with non-genetic risk factors, this may contribute to what has been seen in data from England, where people from the Indian subcontinent are overrepresented among those who become seriously ill,” he said.

The gene is also important in Europe, he says.

“Roughly 5000 years ago, up to 35 per cent of the population had this gene. But over a relatively short period, this percentage has fallen to around 10 per cent today,” he said.

This could be due to the influence of infectious diseases in earlier times, such as epidemics similar to COVID-19, he said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Sources:

The Severe Covid-19 GWAS Group: Genomewide Association Study of Severe Covid-19 with Respiratory Failure, October 2020

Erola Pairo-Castineira et al.: Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in Covid-19, Nature, December 2020