This hat marked the beginning of Norwegian national costumes - the bunads

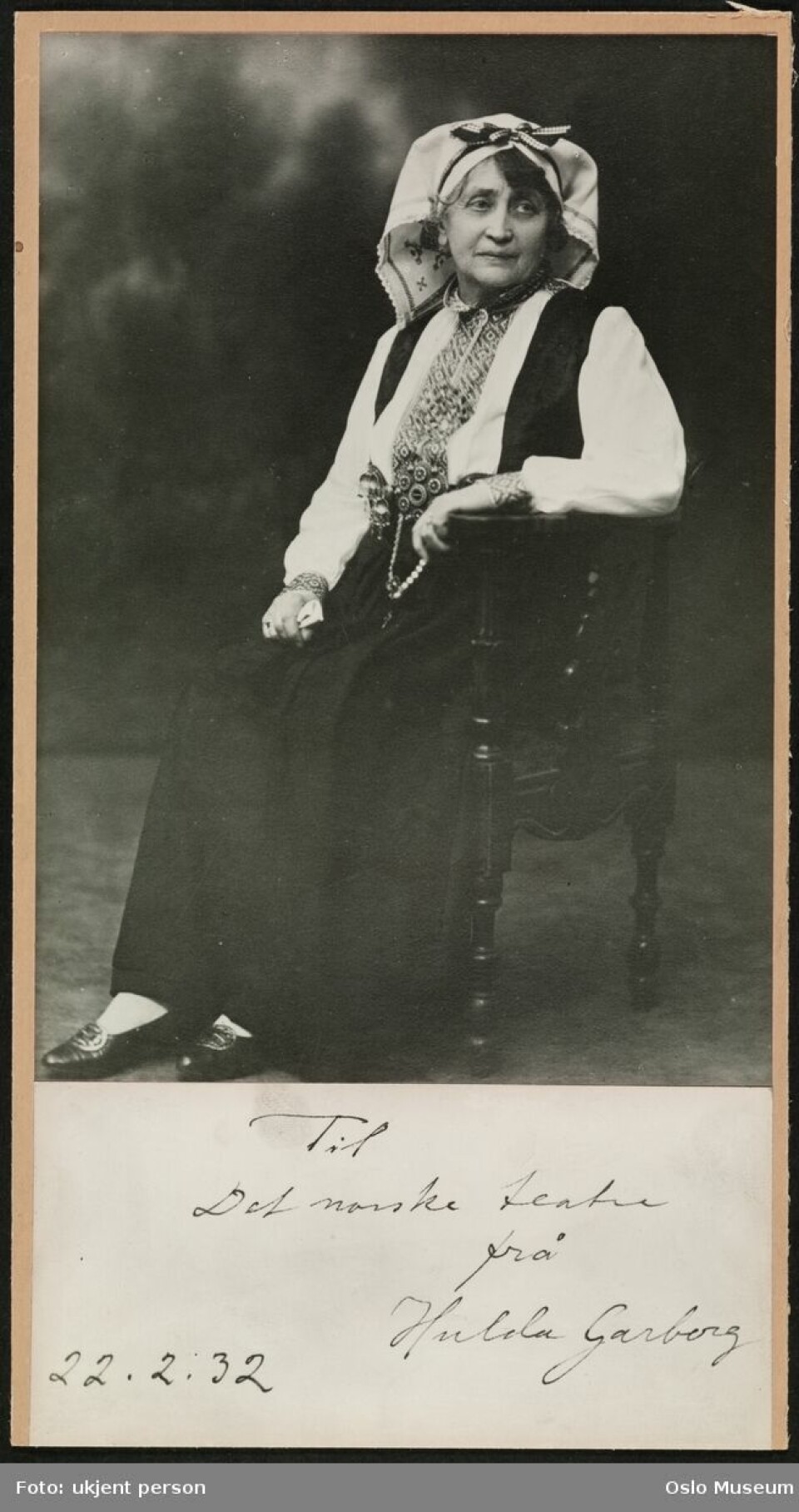

Dark skirts and waists made of wool, with embroidered local patterns. This was how the traditional folk costumes were supposed to be, according to Hulda Garborg - who designed the first bunad.

The year is 1913. It is only eight years since Norway got its own king and full autonomy. A large political movement is working to promote Norwegian traditions - as opposed to the Swedish and international.

Hulda Garborg is one of them. Now she has come to Valdres to make a bunad.

Folk costumes had been in use earlier in the old peasant society before industrialisation. In some villages, women wore such costumes both for parties and as everyday attire. Now they were long out of fashion. Modern fabrics and clothing became more and more common from the end of the 19th century.

Activist and cultural politician Garborg wanted to bring the local, old costume traditions to life. She believed that people should wear costumes from their own villages.

In Valdres, Garborg was shown one garment after another. The new bunad was to be made according to a pattern from older clothes worn to parties.

Did not like silk and damask

“But she didn't like what she saw. Many of the garments were made of imported fabrics in silk and damask,” says Camilla Rossing, head of The Norwegian Institute of Bunad and Folk Costume.

The farmers in Valdres and elsewhere had good access to foreign textiles. Sailors brought home silk and damask, and merchants took the goods further out into the country.

Garborg thought that bunads should preferably be made of wool, with embroidery made in Norway.

“Then Garborg spotted a small hat,” Rossing says.

The seed of Norwegian national costumes

The hat was made of imported velveteen and a traditional pattern was embroidered in wool and silk.

“Garborg fell for the embroidery and the colours. She used this hat as a starting point for the Valdres national costume,” Rossing says.

Garborg received help from Husfliden (who spesialise in old, traditional techniques) in Oslo to make the new bunad. The waist and apron were embroidered in the pattern from the hat.

Author and activist Garborg was likely also inspired by the national costumes that youth teams in Sunnmøre had used in the early 20th century. These were based on traditional dresses with embroidered waists and wool aprons from the villages.

“Together with the bunads from Sunnmøre, the little hat from Valdres is the first seed of our bunad tradition: dark waist, skirt and apron in wool with local embroidery,” says Rossing.

Should be comfortable

In 1917, Garborg presents both national costumes in the book Norsk Klædebunad. They were a real hit.

“The costumes from Sunnmøre and Valdres became enormously popular. People ordered patterns and materials from Husfliden and then they sewed the bunads themselves,” she says. “They were designed to be comfortable to wear.”

The waist was not supposed to be narrow - Garborg wanted women to stop using corsets.

She also wanted the Valdres national costume to be brown and for the colours to be as muted as on the velvet hat.

“But this did not happen. Instead, they were black or blue, and the colours of the embroidery gradually became much stronger,” says Rossing.

Other things have also changed after Garborg set the wool standard for bunads.

From full wool to silk vests

Eventually, other bunad pioneers came along, who had different thoughts on the materials.

“They believed that if people used imported materials in older times, then we can probably use them today as well. This is how national costumes with waists sewn from silk fabrics came to be,” Rossing says.

The institute she heads was originally founded in 1947 as a board under the Ministry of Agriculture. The assignment was to give advice on the production of national costumes.

“After the war, there was a great shortage of materials and a great demand for national costumes,” she says.

Eventually, the board became a council and later an institute with several employees. In 2008 it became a part of Valdres Museums.

"Neither before nor today have we had the authority to approve national costumes, but we assist local forces, such as rural women's teams and history teams, to further develop or make new national costumes,” Rossing says.

Continued explosive power

She emphasises that there is no right or wrong in this area.

“What a bunad is or is not, is in a way up to most people. Here there are fluid transitions,” Rossing says.

It’s been over 100 years since the bunad was an explosive political force in the movement to promote Norwegian traditions.

However, the costume is still a political garment, writes Unni Irmelin Kvam in an article in VG (link in Norwegian). She has several examples:

Pakistani-born Rubina Rana received death threats when she led the parade on Norway’s constitution day, May 17, in Oslo wearing a bunad. Women in the Norwegian parliament wore bunads to dinners at the castle as a protest against the fashion police. In Nordmøre in 2019, activists wore bunads when they protested the closure of maternity wards - an action which has since turned into a movement that calls itself the bunad guerilla.

It is completely in line with how it was in Hulda Garborg's time. The costume gave political signals. Those who wore bunads distanced themselves from society's elite and the union with Sweden.

Documenting the costumes

The six employees at the Norwegian Institute for Bunad and Folk Costume take care of Norway's history and old costume customs.

“There are still large quantities of old clothes in people's homes. We do not collect them, but travel around to document and register them,” says Rossing.

Now the little velveteen hat is on display at Valdres Museums. The exhibition tells the story of ten women who have shaped the history of the bunad. Hulda Garborg is one of them.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

------