What is the rose from the famous Norwegian Selbu mitten doing in the remains of a medieval cathedral in Sudan?

And is it even a rose?

The rose-patterned Selbu mitten is possibly the most knitted pattern in Norway. Traditionally knitted in black and white, the first rose-adorned mittens are to have been made by a young girl called Marit Guldsetbrua Emstad, some time in the 1850s.

The Selbu rose, which adorns both Selbu mittens and the municipal coat of arms in Selbu municipality, in central Norway are also commonly found on Norwegian national costumes, which are called bunad.

Intrinsically Norwegian, one would imagine.

And when she first spotted the same pattern on a pillar on an Island in the river Nile in Sudan, archaeologist Henriette Hafsaas did indeed think of Norway.

“When I came to Sudan and saw this cathedral with these unusual crosses on its pillars, I immediately thought of my Norwegian national costume, my bunad, and the Selbu mittens,” Hafsaas said to sciencenorway.no.

Hafsaas is head of research and an archaeologist at Volda University College. She and Alexandros Tsakos from the University of Bergen discovered an eight-leaf rose on the remains of a medieval cathedral during fieldwork in Sudan.

An academic article on their work was recently published in the Pharos Journal of Theology.

How is it then, that the same pattern appears in two vastly different parts of the globe? Is it simply random?

Hafsaas believes that the connection is Christianity.

The mysterious lost empire of Makuria

The remains of the medieval cathedral are located on Sai, a tiny island in the Nile, located in present-day Sudan. It spans just five kilometres across and is 12 kilomteres long but contains ruins that span thousands of years and several empires, writes atlasobscura.com.

There are ruins there from the foundation of an Egyptian town and temple, as well as ruins of an Ottoman fort, and Islamic cemeteries.

The cathedral in question stems from a medieval Christian empire known as Makuria which flourished in Sudan between the 7th and 14th centuries.

Hafsaas had not thought of the eight-leaf rose as a symbol of the cross, so she was surprised to find it in a Christian context.

“I became quite curious as to why this symbol was on these Christian pillars, and I could not find so many parallels to them either,” she said.

For a while she tried to find an explanation.

At the same time, Alexandros Tsakos was examining written Christian symbols, including the cryptogram for Archangel Michael, also in Sudan. When Hafsaas saw the letters he was working on, she noticed a connection quite by chance.

A cross?

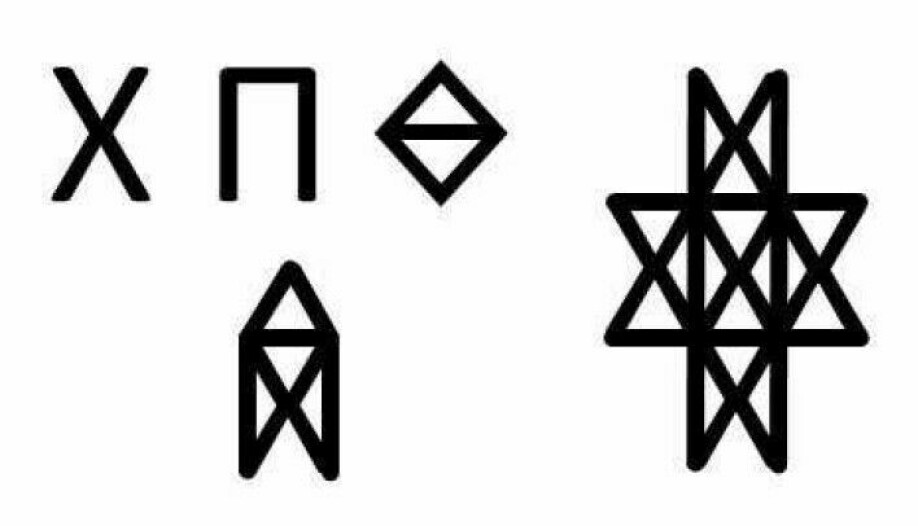

“I saw that if the letters in Michael's cryptogram are placed on top of each other, it becomes one of the elements in this cross,” she explains.

The cross, or rose, comes in different iterations, says Hafsaas. It can be found in mosaics, carved in stone or as a textile pattern, as is common in Norway.

“I think it's actually a cross. Sometimes it's turned like an 'X', and especially in the Christian context it was attractive as a symbol. Another thing that is special about the design of the cross in the cathedral in Sudan is that it can be drawn using one line, without having to lift your writing instrument. It has no beginning and no end,” says Hafsaas.

Cryptic letters

Hafsaas and Tsakos say the symbol is based on a cryptogram that stands for the Archangel Michael.

The Greek name of the Archangel Michael, ϺΙXΑΗΛ, has been divided into different numerical values. Then it has been merged again into a three-digit code. The three-digit code is expressed in letters in the form of a monogram.

In other words, the eight-leaf rose is composed of four such symbols.

Symbol for protection?

In Christianity, Archangel Michael symbolizes protection. This may explain why this symbol is placed on a cathedral — but also on Norwegian garments, Hafsaas believes.

“I think that's exactly why you find it on tablecloths, belts and mittens. These are vulnerable parts of the body that need to be protected,” she says.

She doesn’t think that the symbol was necessarily connected to the Archangel Michael when it came to Norway. But it was a nice pattern that might have something to do with protection, says Hafsaas.

“I think that this cross symbol was particularly associated with Michael in Sudan,” she said

She adds that some doorways in England are adorned with Michael’s monogram. We know from previous studies that doorways were often adorned with symbols or figures to scare away evil forces.

- RELATED You might also be interested in reading this story: This demon wall was supposed to be from the Middle Ages. But it’s only 80 years old — and a fake.

Many motifs recur

“It’s the same with zigzag borders in Eastern Europe. It is said that this means protection. It’s possible that there is a living tradition there, but it is a bit strange when this suddenly crops up in Norway,” said Kari-Anne Pedersen to sciencenorway.no.

Pedersen is an ethnologist and works as a curator at the Norsk Folkemuseum, Norway’s largest cultural history museum. She has studied Norwegian costumes and textiles for decades.

She says she does not know of any older evidence to determine the significance of the eight-leaf rose.

“I'm a little sceptical. There is a great need in our time to find meaning in motifs and symbols. How can we know what people 1000 years ago thought this symbol meant?” she said.

She has no doubt that the rose may have meant something or has been given meaning in Norway as well. Nevertheless, she believes we should be careful not to speculate on how direct the connection is.

"Ethnological research has a concept called spontaneous emergence. We shouldn’t just think that things have been invented somewhere and then migrated. Some things may be so obvious and logical for people to discover that people elsewhere may have discovered the same thing. That’s somewhat where I am when it comes to these motifs,” she says to sciencenorway.no.

“But it can be that they have meant something, or have been given meaning,” she said.

She says many motifs recur both throughout Norway as well as abroad.

Similar pattern from the older Iron Age

“The symbol seems to be older than Christianity, but it became a good symbol to illustrate Christian ideas with since it is cruciform,” Hafsaas said.

There are many similar examples of symbols that are reused in completely different cultures. For example, the simpler Christian cross and the ancient Egyptian Ankh sign.

The Selbu mitten pattern is not that old. As mentioned, the first pair of mittens were made in the 1850s by Marit Guldsetbrua Emstad. But it’s possible that Emstad drew inspiration from older knitting patterns or woodcuts, wrote Sheila McGregor in the book Traditional Scandinavian Knitting, published in 1984.

Marianne Vedeler is a professor in the Archaeological Section at the Museum of Cultural History. We ask if she knows how long the eight-leaf rose has been in Norway.

“There are examples of cruciform patterns in Norway that are similar to ones from the older Iron Age,” she said to sciencenorway.no.

These old patterns are found on piece-woven ribbons.

“You will find similar patterns in many places. They are spread all over the world,” she said.

Difficult to explain why the pattern reoccurs

Vedeler and her colleagues constantly receive inquiries from people who find patterns that are similar to something found in Norway.

“Finding an explanation for this is extremely difficult,” she said.

One explanation they often use at the Museum of Cultural History, however, is that the pattern is logical. It’s an obvious pattern to use when weaving, for example.

“Some geometric patterns are easier to make. Some people have compared these patterns to ones you see when you close your eyes, for example,” she said.

Hafsaas agrees.

“Why do some symbols become very strong? Our brain is good at remembering geometric shapes that have no beginning or end. Maybe it makes it easy to remember these symbols,” she said.

Practical in embroidery - not so much when carving stone

“What I have concluded after working a lot with different motifs is that they are generally practical to make. They work for the particular technique,” ethnologist Pedersen said.

It’s a little different, though, when the pattern is carved in stone rather than when it is used in knitting or embroidery.

“I think it was interesting that it was in stone. But is it in stone because it was originally in textile and then it has been transferred to stone — or?” Pedersen asks.

Perhaps the most exotic find of a similar symbol, the monogram for Michael, was on a mummified body in Sudan, Hafsaas and Tsakos write in their article.

So, is it a rose, a cross, or just a pattern that is logical for our brains to make? Perhaps we will never know.

In any case, Hafsaas and Tsakos work on understanding Christian symbols from the Middle Ages in Sudan is to be continued.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Henriette Hafsaas and Alexandros Tsakos: Michael and other archangels behind an eight-pointed cross-symbol from Medieval Nubia: A view from Sai Island in northern Sudan. Pharos Journal of Theology, 2021.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no