Circular economy offers new kind of consumerism

The world’s population is consuming more and more, as our numbers grow and people become more prosperous. But an increasing number of European countries want to change the way resources are consumed.

We’ve all been there: we buy the latest electronic gadget, use it for a bit, and then toss it away when it breaks or begins to clutter our homes. Increasingly, however, policymakers are seeing the wisdom of curbing this kind of consumerism to live more sustainably on the planet.

One way to do this is to promote a new way of thinking about production, called a circular economy. Under this system, products are made, used, reused, repaired, and when they have reached the end of their useful life, converted into new raw materials.

This approach to manufacturing and consumerism will require a dramatic change across all sectors of the economy. For example, in a circular economy, people would rent objects like cars or garden tools instead of owning them. But how do we transform a worldwide economy that is built on the principle of selling more and more 'things' as a way to profitability?

One group that is trying to help with the transition in Norway is called Circular Norway. Anne Solgaard, who is head of the organisation, says that today’s systems waste too much time and too many resources. For example, she says, a number of metal reserves will be depleted within 30 years.

"We need to reorganise the economy, because the resource situation is somewhat precarious, and we will eventually begin to run out of raw materials. Linear production, where we procure resources, produce and use goods, and then throw them away, is simply not rational,” says Solgaard.

The idea is that we can vastly improve the way we use resources, like designing buildings that are easy to renovate and to disassemble, so that the materials can be reused in other buildings.

Several European countries are already embracing this approach.

On September 1, Denmark’s government released its new strategy for a circular economy. Among 15 concrete measures, for example, the strategy states that authorities should provide financial support for companies that want to make the transition, and that the government should try to push the market in a greener direction through public procurement.

Read More: Just how good are electric cars?

A jacket made from coffee grounds

A recent meeting of the Norwegian Society of Engineers and Technologists (NITO), tackled the issue of the circular economy.

“Engineers and technologists are very interested in the circular economy, because it's about so much more than waste. It’s about how we reuse natural resources and how to design news sustainable products and new technologies,” says Trond Markussen, NITO president.

Erik Aasheim, the meeting’s chair, then took the stage wearing a jacket made from coffee grounds, a suit coat made from fishing nets and shoes made from car tires and plastic bottles.

The Danish chairman of the board of the Carlsberg Foundation, Flemming Besenbacher, was also at the meeting. He ran the committee in Denmark which laid the foundation for the new circular economy strategy.

"Are we talking about an economic revolution?” Aasheim asked Besenbacher.

"Well, I'm not such a supporter of revolution. I'm more about evolution, or as was said here earlier, a paradigm shift,” Besenbacher said.

Read More: Average Danish household has fifth highest carbon footprint in Europe

Not only about waste management

Norway is already good at bringing some products "into the circle" again. The country has a deposit scheme and is quite good at sorting trash. Its residents are also good at recycling electrical appliances and white goods.

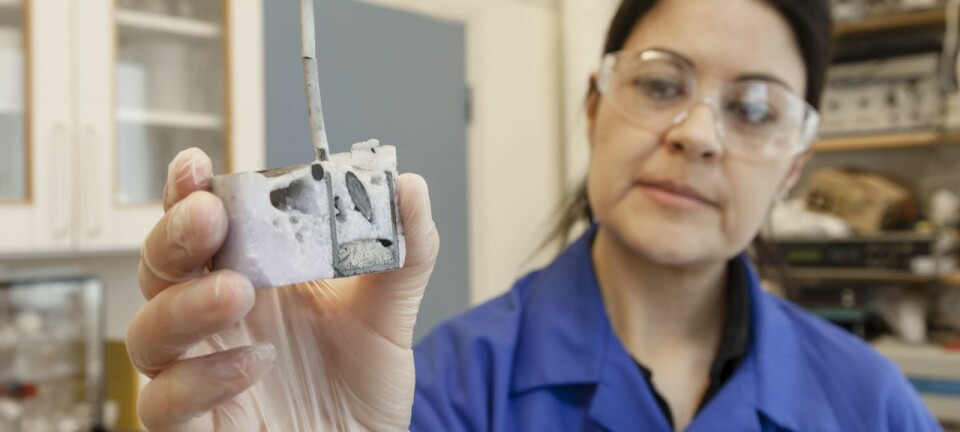

"Many people think of waste management when they hear the term ‘circular economy’. But that’s not what this is about," says Vibeke Nørstebø, a researcher at SINTEF, Norway, who is working on issues related to the circular economy.

"It's about keeping products and materials in use as long as possible and maximizing their value when in use. Repair, reuse, and upgrading, are important ideas here,” she says.

A washing machine is a good example.

"If you develop a high-quality washing machine that can last for many, many years, the product will have a higher value and quality over a long period of time. When the washing machine no longer works, you can repair or replace some components,” says Nørstebø.

Furthermore, Nørstebø suggests that the consumer may not even own the washing machine but the manufacturer or supplier owns it and sells the washing machine as a service. If you want to replace it, the washing machine would be returned to the manufacturer.

“The manufacturer could then maintain or upgrade the machine and re-rent it. This gives them a way to change their business model and encourages the manufacturer to create the best possible product. Recycling is not the focus, here, but making the product last as long as practically possible,” she says.

Read More: More geo-engineering, please!

High ambitions

Cathrine Barth helped found Circular Norway. She described how other European countries are moving ahead with this approach.

"The Netherlands has decided to become ‘wholly circular’ by 2030. They have clear political goals and they are working with businesses,” Barth says.

"For example, by 2030 all new buildings in Amsterdam must consist of at least 50 per cent recycled material and the remainder has to be made from renewable resources. Many people say the materials to do this don’t exist,” Barth says. “But this law has triggered innovative efforts.”

Barth adds that Finland, Portugal, and Slovenia, are also taking steps to implement a circular economy.

----------------

Read more in the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no