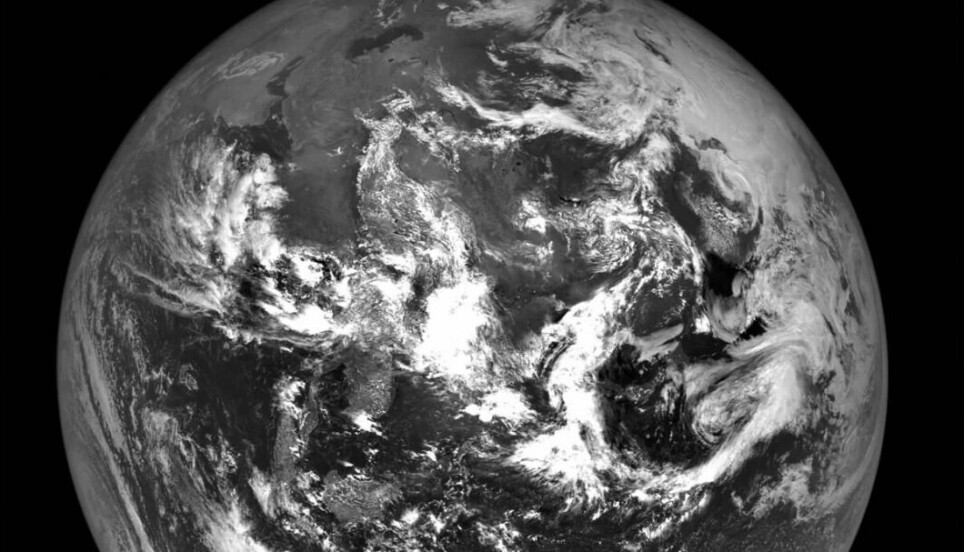

Will the geologists of the future see that something dramatic happened on Earth starting in 1950?

Scientists are considering whether we are entering a new epoch in the Earth's history: the Anthropocene — the age of humans.

At the end of the geological epoch the Paleocene, the Earth’s temperature increased sharply. Fifty-six million years ago, CO2 levels rose, and temperatures increased by five to eight degrees C.

Downpours, drought and ocean acidification followed. A huge number of micro-organisms died out, while on land, mammals underwent rapid development. This is described by geologist Reidar Müller in a new book about the history of the climate, called ‘Ild og is’ - Fire and Ice.

The strong warming and environmental changes 56 million years ago left their mark. Today, geologists can study the event in layers of rock in many places around the globe.

The event is called the PETM (Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum) and marks the transition from one epoch in the Earth's geological age to the next, from the Paleocene to the Eocene.

This is one of the most famous transitions between two epochs. Now researchers are asking themselves if we are witnessing a new transition.

The epoch that extends from the last ice age, 11,700 years ago, and until today is called the Holocene. But has humankind’s footprint on the planet become so large that it will leave a mark in the planet's geological archives forever?

Have we seen the transition to a new epoch, one to be called the Anthropocene — the age of humankind?

To be voted on

A working group has been pondering this question since 2009. They have recommended introducing the Anthropocene, with the 1950s as a starting point.

Now they have identified twelve places worldwide that can be used to define the beginning of the Anthropocene. Here they have identified detailed markers that illustrate humankind’s influence in bogs, on the seabed, in lakes or coral reefs, as has been described in a new commentary in the journal Science.

At the end of 2022, the candidate locations will be voted on. One of them will remain. The proposal must then be voted on by various committees.

The proposal may be rejected along the way, or it may reach the top and be presented to the International Union of Geological Sciences for possible ratification.

If the proposal is ratified, it will usher in a new epoch in Earth's history. We will no longer live in the Holocene, but in the Anthropocene.

Stopped presentation

The term Anthropocene first came into use in 2000, although it had been mentioned earlier. Paul Crutzen, who was a driver behind the idea, was in a scientific meeting in Mexico.

He had previously won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for being one of the researchers who proved that the ozone layer was being thinned at the poles due to the release of chlorinated fluorocarbons, or CFCs, according to an article from The Guardian.

At the meeting in Mexico, scientists presented findings that described large-scale changes on the planet.

Crutzen was visibly upset, according to the article from The Guardian.

During a presentation about the Holocene, he had enough. After hearing the word ‘Holocene’ a number of times, he stopped the presentation and told people to stop saying the word. We are not in the Holocene anymore, he exclaimed.

Another concept was put on the table, the Anthropocene. Anthropos means human.

The idea caught on

Two years later, Crutzen published an article in Nature in which he pointed out the accelerated human impact on the Earth and put it in context with the term Anthropocene.

‘Unless there is a global catastrophe — a meteorite impact, a world war or a pandemic — mankind will remain a major environmental force for many millennia,’ he wrote.

The term caught on among groups other than geologists. It was used in various research fields and in popular culture.

In 2009, a working group was also set up to investigate the geological basis for creating a new epoch.

Belongs somewhere

Reidar Müller is a geologist and author and is associated with the University of Oslo. He thinks the term Anthropocene belongs somewhere.

“I think it's interesting that we are trying to name a period in the Earth's history where a species affects the environment to the extent that we are,” he said.

“The question is whether it is a geologically significant event that means we should call an epoch after it,” he said.

Henrik Svensen is a geologist and associate professor at the University of Oslo.

He thinks the term is both useful and interesting.

“I think it would be useful because I myself work with sediments and see the value of being able to define the start of a new epoch,” he said. “It’s interesting because it has brought with it many new terms and interesting discussions.”

The umbrella of the Anthropocene can include discussions about among other thigns tipping points, planetary tolerance limits and the sixth extinction.

The concept is not just a proposal that deals with technical terms within geology, it also has a political dimension.

“Clearly, there was probably a political motivation on the part of those who proposed this in the first place. It was an effort to try to put a label on the fact that we have made very big changes and that we should perhaps do something about it,” Svensen said.

Fertilizer and oil

This time it is not the ravages of volcanism or a meteorite that is blamed for starting a new epoch.

What kind of changes might affect the Earth to the extent that it marks the start of a new age?

We have changed the geochemical cycle of nitrogen and phosphorus, says Müller, as one example.

“We use enormous amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus, which we pump into the ecosystem via artificial fertilizer,” he said.

As is known, the CO2 content in the atmosphere has risen rapidly and is probably the highest it has been in at least three million years. The temperature has also risen rapidly by just over one degree globally.

Enormous amounts of oil, gas and coal have been burned over relatively few years, from a geological perspective. Müller's latest book describes it like this: Every day the world burns 95 million barrels of oil, or enough barrels that if they stood next to each other, they would encircle the globe at the equator.

Oil was once plants and algae that pulled carbon out of the air and were buried. This carbon is now being fed back into the system.

Chicken bones

Humankind has also reshaped the landscape. Rivers and lakes have been dammed and regulated, while gravel, stone, metals and coal have been extracted from the ground. Large areas have been transformed into pastures and fields. Cities and buildings have been erected. Forests have been cut down to use the areas for something else.

“We have removed as much forest as the area of North America since civilization began, and we continue to expand,” says Müller.

At the same time, there are very many more of some types of animals and very many fewer of others. Livestock accounts for 60 per cent of the total weight of all mammals. All wild mammals make up only four per cent.

Chicken is now the most abundant vertebrate on land. Jan Zalasiewicz, who previously led the Anthropocene working group, believes that chicken bones will become one of the fossil markers of our time.

Other changes are that species have spread with humans to new areas and that biodiversity is threatened.

“If it continues as it is now, if we fail to stop the sixth extinction that is being widely discussed, we will certainly see in the future that species diversity has decreased. You will also see that some species have become very dominant, such as chickens,” says Müller.

Can't match the ravages of the Ice Age

At the same time, humans can’t match other forces that have left their mark on the Earth in prehistory, Müller said.

“Take the last ice age, which reached its maximum 20,000 years ago. The glaciers moved enormous amounts of rock and gravel. Glacial ice carved out fjords and valleys. Compared to the power of the large ice sheet, we haven’t affected the landscape that much yet,” Müller said.

Disagreement about starting point

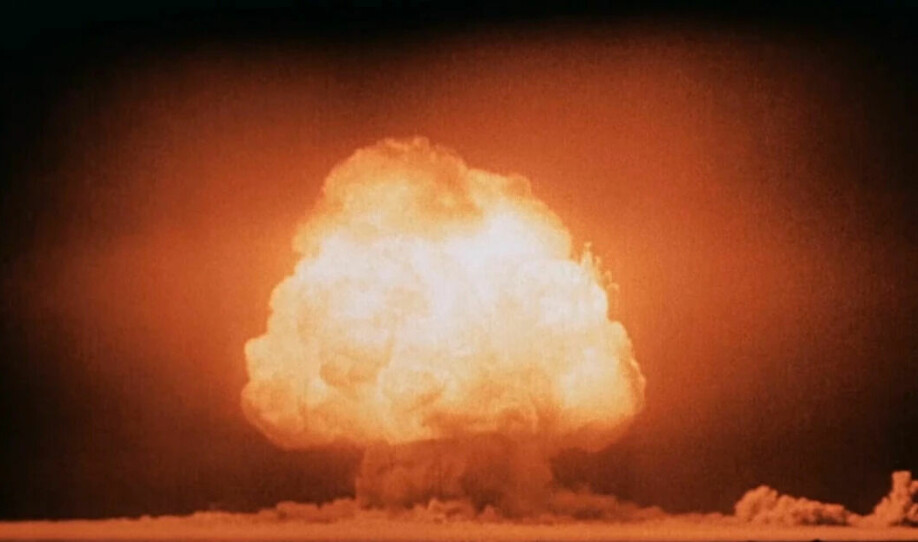

The researchers in the working group believe that the new epoch should start in 1950. This coincides with what has been called ‘the great acceleration’.

From 1950 onwards, the arrows point upwards in many areas: the number of people, production of goods, energy consumption, travel, water consumption, fertilization, loss of rainforest and so on.

Not everyone agrees that 1950 is the best starting point, however. Humankind has influenced the globe for several thousand years. Hunters and gatherers were involved in exterminating large animals long before civilizations emerged.

“As a geologist who is concerned with the deep time, I think it is exciting to draw the boundary to the Anthropocene a little farther back in time, such as back to the agricultural revolution, where large areas were cultivated or converted to pasture,” Müller said.

Some say that this had already led to a slight increase in both methane and CO2 in the atmosphere several thousand years ago, says Müller.

“One of the biggest natural interventions in the Norwegian environment was the burning down of the forest along the Norwegian coast from Lista in the south to Lofoten in the north to turn it into pasture. These are huge natural interventions that happened several thousand years ago,” he said.

Have taken samples

Others have suggested putting the starting time at the Industrial Revolution.

“There are many different ways of looking at this issue. But the starting point must be possible to measure,” Svensen said.

The Industrial Revolution did not start at the same time everywhere and will not be as easy to measure in the Earth's archives. As a result, the idea was abandoned, and the working group landed on 1950.

In the new article in Science, twelve places are described that have been proposed to define the start of the Anthropocene.

“The article is a kind of status report and a good review of the problem,” Svensen said.

At the twelve sites, samples have been taken, mostly core samples: long pipes stuck into the seabed or into the ground.

Microplastics and plutonium

One of the places the researchers have singled out is Beppu Bay, a bay in Japan that contains several types of markers that can be used to determine the start of the Anthropocene.

The water in the bay’s depths is quiet and oxygen-poor. Here, layer upon layer of material has accumulated on the bottom over time and has lain relatively undisturbed.

In a core sample of around one metre, the researchers can look back on the last 1,300 years.

From 1965, special carbon particles originating from the combustion of oil and coal appear. This is a marker of human activity that can now be found on all continents, including Antarctica, according to the working group's website.

The sample also contains DDT, an insecticide, the environmental toxic substance PCB and a strong increase in microplastics after the 1960s.

The researchers also identified a change among the microorganisms in the environment and the type of pollen that ended up on the bottom. This is due to more input of nutrients and changes in land use in the area.

The sample also includes increases in plutonium originating from radioactive fallout from nuclear test explosions in the 1950s and 1960s.

Gold spike

The other locations contain the same or different markers.

The researchers are looking for a place to stick a ‘golden spike’. In several places, a physical gold-coloured nail has been hammered in to mark the distinction between two time periods in layers of stone. But the nail doesn't have to be physical.

“You have to find a type of locality that has the best properties. The layers can’t be too thin, and there shouldn’t be any missing sediments, so that we are sure that the geological archive is complete,” Svensen said.

Global signals

The researchers are looking for signals that can say something about population growth, climate and industrialization, he said.

If, for example, you take a core from the bottom of a lake, you don't want to just find out what was going on at the neighbouring farm.

“They are looking for global signals,” he said.

Among these signals are plastic pollution, traces of alien species and chemical traces, such as a change in the ratio between isotopes of nitrogen and carbon.

“When you burn oil and gas, more of one type of carbon, a carbon isotope, is released into the atmosphere. There will be more carbon 12, compared to carbon 13,” Svensen said.

What will future geologists find?

Will a geologist find traces from our time a hundred thousand or a million years into the future?

“I believe so yes, absolutely. But it depends on what you want to measure and how it relates to the start of the Anthropocene,” Svensen said.

“A concrete example is Norway’s fjords, where there has been a lot of industry and where a lot of heavy metals have been washed out into the ocean and deposited. This is quite different from what has happened in the past, millions of years ago. Now there’s a lot of lead, copper, nickel and zinc, for example.

“This would show up as a very clear anomaly, or a separation, which would last quite a long time geologically speaking,” he said.

You would also be able to detect lead from when people started using lead in paint on boats at the end of the 19th century, Svensen said.

Remains of cities

It is not certain that traces of this time in our civilization will be found everywhere. But where there have been large cities, the evidence should be clear.

“If or when the next ice age comes, then everything we have created in Norway, all of the human infrastructure, will end up in Skagerrak as a kind of coarse-grained sedimentary rock of buildings, concrete, metal and asphalt,” Müller said. Skagerrak is a strait that lies between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, Norway’s south-eastern coast, and Sweden’s west coast.

If that happens, it’s likely there will also be traces of radioactive fallout, changed geochemistry, changed species composition and so on.

Counterarguments

Not everyone thinks a new epoch should be introduced.

“The counterarguments can perhaps be divided into two,” Svensen said.

“There are those who are sceptical about focusing more on climate change and environmental problems and who may not think that it is a big problem,” he said.

Another type of objection is that it must be possible to measure the Anthropocene from a practical standpoint in the same way that transitions between other eras can be measured.

“If you can't measure it, then you can't use it either, and then it's not very useful. That’s a relevant objection. That’s exactly what the working group is doing, they are trying to turn the idea and concept into a useful geological tool,” he said.

Wait for 1,000 years?

One of the critics is the Secretary General of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), Stanley Finney, according to a 2019 article from The Guardian.

Finney has believed that it is speculative to assume that human influence will one day be readable in stone.

Other counterarguments are that we are now in the middle of what is happening. People will need some distance before it can possibly be decided when a new epoch begins.

One of the members of the working group has previously suggested that the question should be put on hold for, for example, 1,000 years, Nature wrote in 2015.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Colin N. Waters & Simon D. Turner: Defining the onset of the Anthropocene. Perspective, Science, 2022.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no