What actually started the Little Ice Age?

It all may have started with sea ice, and the changes may have happened all by themselves without the influence of volcanoes or the Sun, researchers behind a new study say.

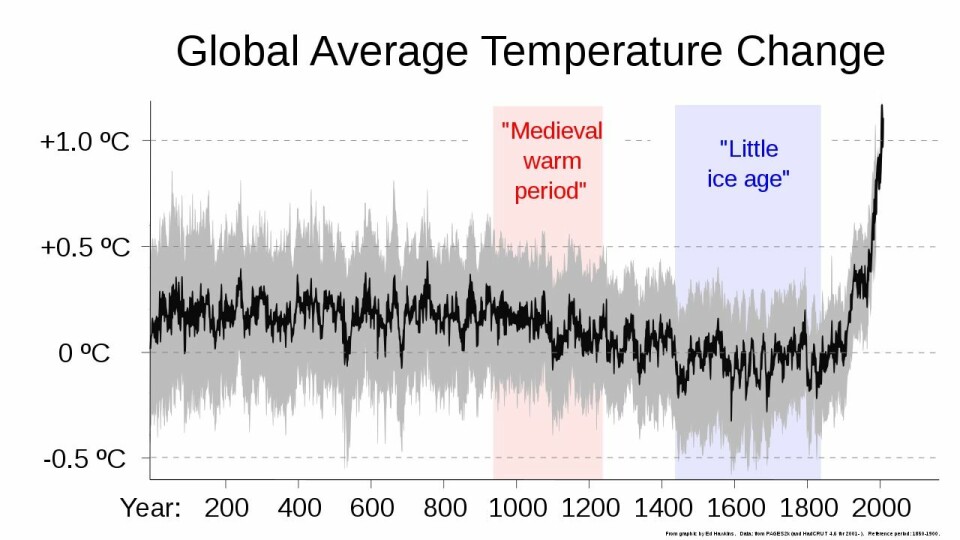

The ninth century seems to have experienced a warmer climate, which has been called the Medieval Warm Period.

But from the 14th century things were different. It rained "without stopping" in 1315, and grain didn’t ripen. The situation was much the same the following year. Later in the 14th century there were several episodes of wild weather and cold periods.

The Little Ice Age can be divided into two phases, according to an article in The New Yorker. It began with a cooling period in 1300 - 1400. The coldest period was from the end of the 1500s to 1850.

This cooling caused glaciers to expand in Scandinavia, the Alps, in Iceland, Alaska, China, in the southern Andes and in New Zealand.

Londoners were able to skate on the Thames now and then. In France and Switzerland, advancing glaciers crushed villages, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Wet summers and icy winters led to poor crops and famine for several years in Northern and Central Europe.

What started it all? Researchers behind a new study have an unusual proposal.

They suggest that the cooling may have occurred spontaneously and by itself.

Ugly ducklings

Generally speaking, the Little Ice Age is said to have begun because of an increase in volcanism and reduced activity of the Sun.

A large volcanic eruption in 1257 followed by three smaller eruptions through the end of the13th century have been suggested as the cause of the Little Ice Age. Aerosols from the eruptions may have shaded the Sun and made the Earth colder. Thereafter, feedback related to northern sea ice ensured that there were cold periods long afterwards.

“The timing agrees quite well with the great eruptions from the 13th century. So there is good empirical evidence that this could be true,” said Martin Miles, a researcher at NORCE Norwegian Research Centre, and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research in Bergen, and at the University of Colorado at Boulder in the USA.

But in a new study, Miles and his colleagues have looked at another possibility.

Sometimes climate models behave strangely. These models may show sudden changes in the north, without added climate drivers such as volcanism or changing solar activity. These computer runs have been called "ugly ducklings", because they seem to have something wrong with them.

But it is not clear that these computer simulations are wrong.

“It may be that changes in sea ice and sea ice outflow from the Arctic Ocean have happened randomly due to internal variability in the climate system. Maybe these models, which people are sceptical of, are actually correct,” says Miles.

Lots of ice on the go

In their new study, Miles and his colleagues looked at the transport of sea ice from the Arctic over a 1400 year period.

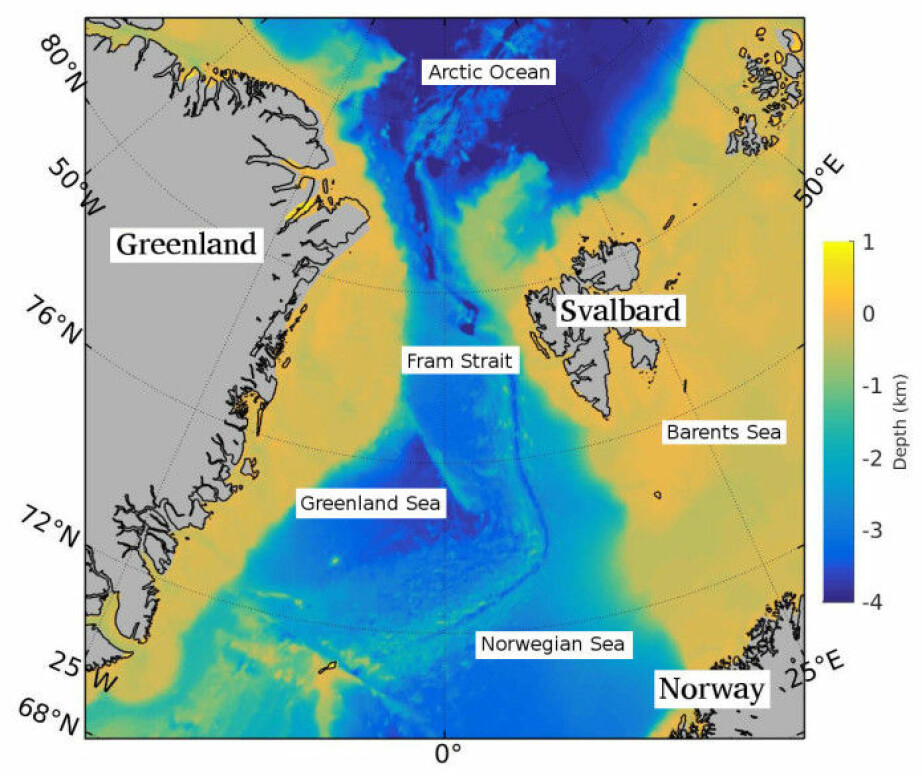

They compiled data from seabed samples from areas outside Greenland, the eastern part of the Fram Strait, the Greenland Sea and off Iceland. The samples contained small fossils that give researchers information about sea temperatures and loose material that sea ice had carried with it.

In several of these areas, ice will only be found if there is an especially large amount flowing out of the Arctic Ocean. This is particularly true during cold periods and when there is also a lot of sea ice formation.

“We discovered that an unusually large amount of sea ice flowed out of the Arctic Ocean from the beginning of the 14th century. It is very interesting, and the biggest event we found during the last 1400 years,” says Miles.

“It happened right around the start of the Little Ice Age. This indicates that it was very important, and was perhaps a necessary kickstart for the Little Ice Age.”

A lot of ice flowed out of this region for almost 100 years. At the beginning of the 15th century, ice flow decreased, but the amount of meltwater in the area had increased and remained elevated for a long time afterwards.

The transport of sea ice is due to wind fields that also affect ocean currents in the Arctic Ocean, Miles said. Most of the ice exits the area through the Fram Strait, and amounts vary a lot.

“In some periods, there’s a lot of ice, such as during the Great Salinity Anomaly in the 1960s. For three or four years, an unusual amount of sea ice flowed out through the Fram Strait, which had an impact in the Nordic seas for many years afterwards. What we have discovered is very similar to the Great Salinity Anomaly, but it lasted much longer, almost 100 years,” he said.

Can’t explain everything

Miles says sea ice may have affected the climate in Europe in the 14th century in this way.

The ice that melts and turns into fresh water can affect ocean currents, which in turn affect the atmosphere and climate, he says.

“Ocean currents are very important for transporting heat to Europe. If the currents weaken a little, it will be much colder than usual,” he said.

Sea ice is not only a reaction to climate change, but can also trigger climate change, Miles says.

However, sea ice changes during the 14th century can’t fully explain why it was cold for several centuries during the Little Ice Age.

“There must have been some kind of influence or event during the period afterwards for it to continue to be relatively cold. There was a lot of volcanism during the Little Ice Age and three or four periods with less solar radiation. So it is not necessarily just the one incident that can explain everything, of course,” Miles said.

During the Little Ice Age, global temperatures dropped by about 0.5 degrees C. But it was not the same everywhere.

“The Little Ice Age was certainly not global. More and more researchers have found that it was regional and that it was not completely cold throughout the period. There was a lot of variability from place to place. I think the best expression for the period is ‘the European Little Ice Age’, because it was mostly the North Atlantic, Greenland and Northern Europe that were affected,” he said.

Previous study supports the findings

The results of the new study are supported by geologist Willem van der Bilt, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bergen.

Van der Bilt led a study published last year, in which he and his fellow researchers promoted the idea that growth in Arctic sea ice may have occurred spontaneously at an earlier stage.

He and his colleagues used geological data to look at the distribution of sea ice and glaciers on land. They found that sea ice in the Arctic advanced a few centuries before the Little Ice Age, between the years 650 and 950. During this period there was little volcanic activity, and more stable solar activity, according to the article published in Quaternary Science Reviews.

“In both the new study and in our work, we see that there is a fairly dramatic increase in sea ice cover through the region. This seems to coincide with all other types of evidence for cooling in the area,” van der Bilt said.

“People have long argued that this type of change must have been triggered by external influences, such as volcanic eruptions and the amount of solar radiation that hits the earth's surface. But the timing of these changes in our study does not really fit with this,” he said.

Van der Bilt and his colleagues also took a closer look at the ugly duckling models. They found that the changes they discovered were similar to what happened during these anomalous model simulations.

Still an open question

Van der Bilt thinks we need to be aware that abrupt climate change may have taken place in the past, without any external drivers or mechanism to cause it.

“Broadly speaking, this could open our eyes to the possibility that abrupt climate change is an inherent feature of the Earth’s climate system, in that there are now a couple of studies that show this has happened at different times,” he said.

Van der Bilt thinks it is gratifying when theoretical climate models and actual data from the past support the same findings.

“It’s quite valuable in helping us better understand whether the climate models are correct or if something interesting is happening that we can’t really explain. We can compare our different datasets and work together to better understand what the climate system may have in store for us in the future,” he said.

Miles says it remains an open question whether the Little Ice Age and other past changes in the climate may have occurred spontaneously.

“We have focused on only one incident. But it looks like there were perhaps four or five of these in the past. The next step will be to see if we can map these and check them against volcanic eruptions and solar variability. That may help us figure out if they happened by chance or were due to other influences,” he said.

But today's climate change is not accidental, says van der Bilt.

“We have an incredible understanding of how our planet is changing. We can see the changes in the sea day by day and measure temperatures around the world,” he said.

“This allows us to say that yes, today, what we see is definitely driven by what our species has done to the atmosphere when it comes to greenhouse gases, which is a very different climate mechanism.”

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

This article was updated on October 26th 2020.

References:

Martin W. Miles et.al.: “Evidence for extreme export of Arctic sea ice leading the abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age”, Science Advances, 2020.

Willem van der Bilt et.al.: “Was Common Era glacier expansion in the Arctic Atlantic region triggered by unforced atmospheric cooling?", Quaternary Science Reviews, 2019.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no