Scientists are seeing ice age beginnings for very first time

Some fantastic 3D images have emerged from the bottom of the North Sea, making it possible to document the beginning of the ice ages 2.6 million years ago.

“We were enthusiastic, to say the least, when we understood what these new 3D images from the North Sea could show us.”

“Suddenly we were sitting on fantastic data,” says geologist Helge Løseth.

The last two million years or so have seen somewhere between 30 and 40 ice ages in a row. This relatively short ice age period brought an awful lot of changes to Norway.

We see the results quite clearly in the form of fjords, mountains, valleys and the low plains along the coast from Trøndelag and northwards.

But we know surprisingly little about what was really going on – especially at the beginning of this last and very dramatic period.

Much better preserved in North Sea

The remains of both the ice ages and earlier periods in the Earth's history have been much better preserved on the continental shelf in the North Sea than on land in Norway.

On land, the ice ages themselves effectively removed almost all traces of them, except the very largest indications that we see today as valleys, fjords and towering mountain peaks. There may have been as many as 40 ice ages. But we only see the traces of the last one, which lasted for 100 000 years.

In stark contrast to this, the new 3D images from the North Sea seabed can tell geologists in detail about the development during all the ice ages, all the way back to the beginning.

This information is largely due to the fact that the North Sea is now probably the best mapped seabed in the world.

Very first ice flowed out of Sognefjorden

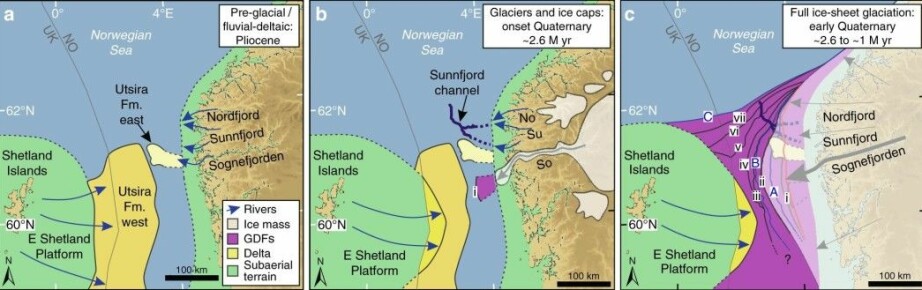

When the first thick glacier covered Norway 2.6 million years ago, it sent giant glacier arms out to sea, like glaciers are still doing in Greenland and Svalbard today.

“The very first glacier arm probably came out where Sognefjorden meets the sea", says Løseth.

Eventually glacier arms extended out from the Nordfjord, Sunnfjord and Hardangerfjord systems. The ice that flowed from the mainland spread beyond the continental shelf.

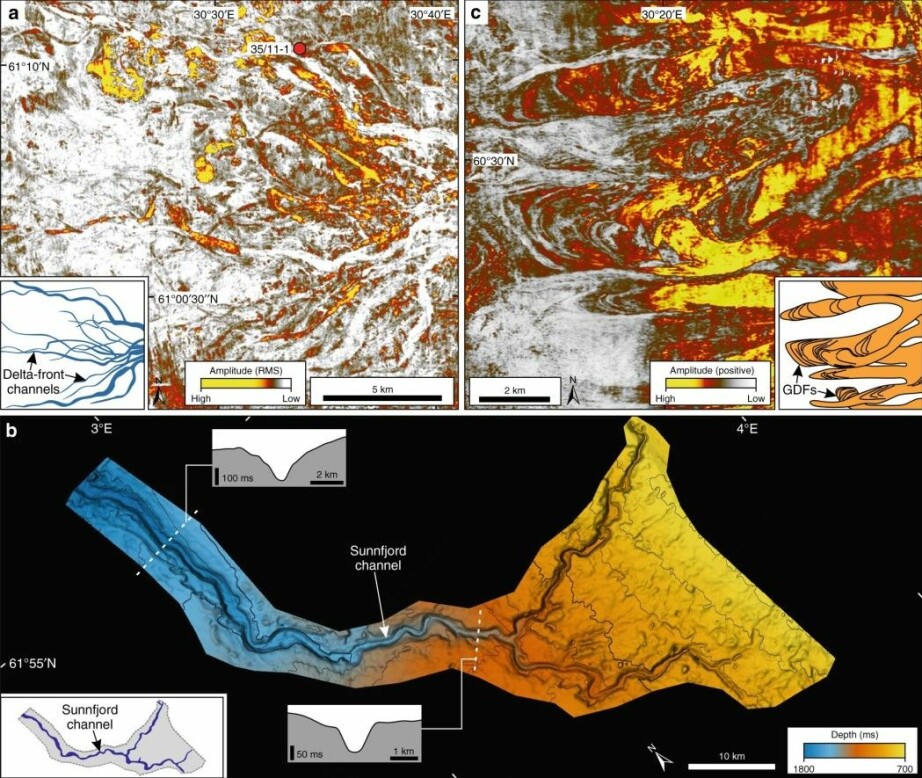

Sunnfjord channel over 100 kilometres long

At Sunnfjord in the north of Western Norway, a large river of meltwater might have sent huge amounts of water into the sea during the beginning of the very first ice age.

The meltwater continued as a strong underwater stream. At least 100 kilometres to the west, it dug a deep canal on the seabed.

“The Sunnfjord Canal is up to two kilometres wide and 150 metres deep.”

“We can see that the sediments in the canal are younger than the river deposits that came out of Sognefjorden valley just before the ice age, but older than surrounding masses that were also deposited during the ice ages. This is how we’ve been able to establish the time of the Sunnfjord channel to the beginning of the ice ages,” says Løseth.

Researchers have only been able to locate the outer part of the Sunnfjord channel in the 3D images. Further inland on the shelf, both the Sunnfjord channel and other traces on the seabed have been removed by the ice masses that flowed along the South Norway coast and out into the ocean and scraped the ocean floor. The broad Norwegian Trench was formed by this ice stream activity.

A much bigger Shetland

Today Shetland is a small archipelago on the western side of the North Sea.

But just 2.6 million years ago, Shetland was a much larger land mass.

“Strangely enough, this land wasn’t covered by ice during extended periods of the ice ages,” Løseth says.

“Instead, large rivers flowed out of Shetland during the ice ages. They brought with them sediments that encircled Shetland on the continental shelf.” (See the figure below.)

Researchers can now see how the water from the rivers in the Shetland land mass met river water and glaciers that came from Norway. The images show how masses that were carried into the ocean from Norway and Shetland were deposited on the seabed.

Here is more about what happened at the very beginning of the ice ages:

Discovering layers upon layers of ice age history

Løseth, with research colleagues at the Norwegian Geological Survey (NGO) and the University of Cambridge in the UK, have now published an article in the journal Nature Communications where they use the 3D images from the bottom of the North Sea.

The researchers talk about how they have identified layers from different parts of the ice age in what they call a seismic sequence. They see layer upon layer – the time from before the ice ages set in until the emergence of a full ice age – and in fact all the way to today's seabed. They can also observe traces of the giant Storegga Slides from the Stone Age.

The researchers for the new Nature article are also the first to believe they can confirm that the ice, from the very beginning of the ice ages, stretched far out to the edge of the continental shelf in the North Sea.

And there it broke apart into enormous icebergs.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Helge Løseth et.al: 3D sedimentary architecture showing the inception of an Ice Age, Nature Communications, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16776-7

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no