Forests absorb less CO2 than before

Why do forests absorb less carbon dioxide than 15 years ago?

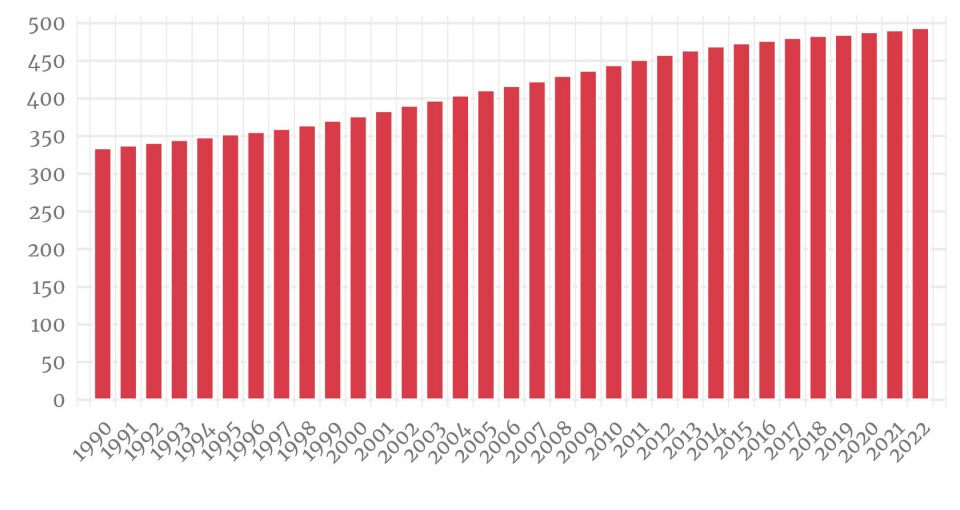

Over the last hundred years, Norway’s forests have tripled in volume, according to the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research - NIBIO (link in Norwegian). This has resulted in large amounts of CO2 being removed from the air and stored in trees, leaves, dead trunks, and in the ground.

This is because the growth of trees in forests has been higher than the rate of logging and natural tree death.

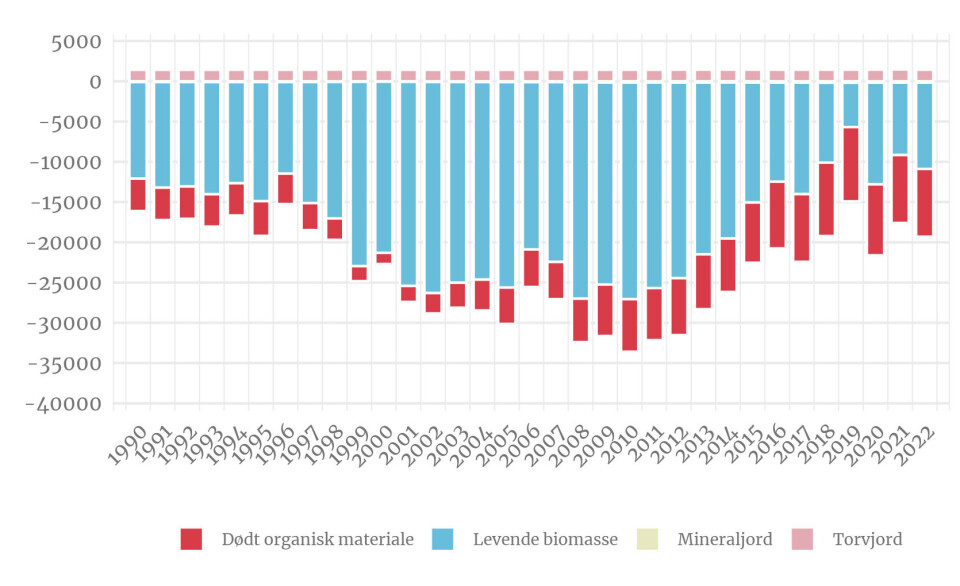

The amount of carbon stored in forests continues to increase every year. 28 per cent of Norway's emissions are captured by forests and land use, according to the Norwegian Environment Agency (link in Norwegian).

But the annual increase has declined since 2010, as reported by online newspaper Energi og Klima (link in Norwegian).

In 2010, forests absorbed a net 32 million tonnes of CO2. By 2022, the figure had dropped to 18 million tonnes.

Like easing off the pedal

Christian Wilhelm Mohr, a researcher at NIBIO, helps create the official account of CO2 absorption and emissions from forests and other areas in Norway.

Mohr compares it to driving a car from A to B.

“If you press harder on the pedal, you’ll reach the goal faster. This represents the increase in net CO2 absorption in forests. What we see now is a slowdown, like easing your foot off the pedal. Net absorption is steadily weakening,” he says.

Mohr adds that eventually, we could reach a point where we start moving backwards. This would correspond to net emissions, meaning that forests lose more carbon than they absorb.

A CO2 sink

Mohr finds the trend somewhat concerning.

“It’s worrisome when it starts to level off. Suddenly, it can go in the other direction, where the loss of living biomass is greater than the uptake,” he says.

The other sectors in the climate accounts – energy, industry, waste, and agriculture – are net emission sectors, according to Mohr.

“The land sector is currently a net uptake sector,” he says.

If this changes, it would be bad news for Norway's efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The age of trees

The decline in CO2 absorption has partly historical roots. In the early 1900s, forests were heavily logged and sparse. After World War II, large-scale tree planting efforts began.

Between 1955 and 1992, over 60 million trees were planted annually, according to the Norwegian Environment Agency. This increased the CO2 uptake in forests.

“Young trees absorb little CO2. As they grow, their absorption increases significantly. However, as trees age, their uptake starts to decline again,” he says.

Forests that have stood for a long time have aged and now absorb less CO2, Mohr explains. Natural tree death has also increased, according to the article from Energi og Klima.

Another reason is that many of the trees planted decades ago have now matured and are being logged. Logging has increased, says Mohr.

New trees are planted on logged areas, but it takes time before their CO2 absorption increases again.

Deforestation in Norway?

The age of the trees alone cannot explain the entire decline, says Mohr.

Deforestation is also a contributing factor.

Deforestation converts land from forest to other uses, such as buildings or farmland. Logging, on the other hand, is the management of forests.

“Deforestation removes trees, dead wood, litter, and often soil to repurpose the land. In contrast, logging involves replanting trees, which will help absorb CO2 in the area again,” he says.

The forest area has slightly decreased, from 37.7 per cent of land area in 1990 to 37.5 per cent in 2022.

Annually, 60,000 decares are deforested, while 36,000 decares of new forest are planted and grown, according to the Norwegian Agriculture Agency (link in Norwegian).

“Approximately one football pitch is deforested every hour in Norway,” says Mohr.

Two-thirds of the deforested land goes to housing, cabins, roads, railways, industry, and other uses, while one-third goes to pastures and fields, according to the Norwegian Agriculture Agency (link in Norwegian).

What about the reforestation?

While some areas are deforested, new forests are growing in mountain regions and in old pastures.

“Some people say that Norway is regrowing,” says Mohr.

However, the areas with new forests often have poorer growth conditions compared to areas where forests are being removed.

“Part of the problem is that much of what is removed is what we call productive forest. These forests absorb a lot of CO2,” he says.

Productive forests are in lowland areas where trees grow large and healthy. When new forests grow in higher altitudes, it has less impact on the national CO2 uptake.

Lowland forests account for 94 per cent of the carbon storage in living biomass, while mountain forests account for only 4 per cent, according to NIBIO (link in Norwegian).

Less deforestation

It is also possible that climate change has an impact, says Mohr. Climate change can increase forest growth but also lead to tree death from extreme weather, such as the drought in 2018.

How can forests absorb more CO2?

Reducing deforestation of productive forests is a short-term measure that can be taken, says Mohr.

In particular, we should avoid developing on peatlands or other soil layers rich in organic material.

Interesting

Jogeir N. Stokland, a senior researcher at NIBIO’s Division of Forest and Forest Resources, agrees that increased logging, natural tree death, deforestation from lowland development, and possibly climate change have contributed to the reduced CO2 absorption in recent years.

No one has yet calculated the precise impact of each factor, according to Stokland.

“The data to do this is available, and calculations should be done for forest areas as a whole and broken down by different forest types,” he says.

Stokland thinks this would be interesting to investigate.

Logging and natural tree death

Climate change impacts forests in multiple ways.

“My understanding is that climate change allows existing trees to grow better due to a longer growing season. However, faster growth also slightly increases their probability of mortality. Trees need to grow slowly to live longer,” says Stokland.

Both logging and natural tree death have significantly increased, says Stokland.

Looking at the numbers, it seems that increased logging has had a greater impact than annual losses due to natural tree death, says Stokland.

“The area of mature forest has been large for 20 years. It’s more the price of timber that has driven the increased logging rather than the age distribution in forests,” he says.

Still a significant carbon sink

Stokland points out that despite the decline in CO2 absorption, there are differences between tree species. Particularly in spruce forests, the decline is significant, as NIBIO has recently noted (link in Norwegian).

“Even though absorption has decreased, forests remain a significant net carbon sink, and they will likely continue to be so,” he says.

There is no indication of a dramatic increase in forest death, says Stokland. The drought summer of 2018 increased mortality, but less than in the 1970s when two consecutive drought summers allowed the spruce bark beetle to gain the upper hand.

Two strategies

Stokland explains that there are two strategies for using forests to improve Norway's climate accounts in the future.

One strategy is to log forests and use forest products to replace fossil materials.

“That’s beneficial. The other strategy is to use forests for carbon capture, which also helps mitigates climate change,” says Stokland.

You cannot do both, logging and preserving the forest, on the same land.

“But it’s an interesting discussion on how much emphasis should be placed on the two alternatives in different forest areas,” he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik