Is it true that trees talk to each other?

A fantastic idea and a popular science book that has sold millions of copies claims that they do. This is laying it on too thick, according to Norwegian biology professor, who warns against 'disneyfication' of research results.

A group of researchers at the University of Alberta in Canada has now collected the results from a large number of different studies to find answers about the contact trees have with each other underground.

Millions of enthusiastic book readers and documentary film viewers have picked up on author Peter Wohlleben's claim that trees live a secret life.

A life where they talk to each other, show love, and feed their children.

But is this true?

A Wood Wide Web underground

Wohlleben bases much of his hugely popular book on Canadian researcher Suzanne Simard. She has become popular among journalists and filmmakers.

Simard and others have developed a theory that the trees have a Wood Wide Web underground.

A network of fungal threads that they use to send signals and nutrients to each other.

Through the Wood Wide Web, trees can also convey feelings such as love and pain to other trees.

Several documentaries have been made about Wohlleben and Simard.

They have also inspired fictional films like Avatar.

Below is the trailer for the documentary Intelligent Trees, where Wohlleben and Simard present their theories.

(Video: Libelle THE SERIES / YouTube)

The problem is evidence

Justine Karst is a researcher who has taken on the task of examining Suzanne Simard's research findings and Peter Wohlleben's claims more closely.

“The problem is that there is so little evidence that any of this is true,” mycologist (mushroom researcher) Karst tells the magazine New Scientist.

Karst and her colleagues have gone through more than 1,600 published studies.

These are all studies on the structure and function of fungi that grow on the roots of trees.

Network of fungal threads

Karst and other mycologists can confirm that there are large networks of fungal threads underground. These threads can stretch between trees and between plants.

However, Karst and her colleagues point out that several key claims about the collaboration between trees and fungi made by Simard and some other researchers – claims that have been widely repeated in the media and literature in recent years – are only based on very few studies.

So far, researchers know little about how far such fungal networks between trees extend underground. They also do not know if it is really possible for trees to communicate through such networks, according to Karst and her colleagues.

The researchers also looked for studies that could confirm the claim that trees help their children by transferring nutrients to them via underground networks.

Here, they found even less evidence in the research that has been done.

Laying it on too thick

Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson is a biology professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU).

When Peter Wohlleben's book came out, she was not as enthusiastic as many others.

She felt that he was laying it on too thick and going far beyond what he had evidence for.

“The forest is an amazing place. Much of what happens in nature is surprising and fascinating,” she says. “Is it then necessary to drown out the facts with inaccurate claims, such as that trees are ‘friends’, have a ‘language’, feel ‘terrible pain’, give out ‘love’ and ‘social support’, and are concerned with ‘fair distribution’?”

These are claims that Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson believes are supported to a very limited extent by researchers who could have confirmed this.

Exaggerating the humanisation of plants

“This is exaggerating the humanisation of nature. There is something about Wohlleben's whole explanation model – or rather, the absence of explanations – that jars my ears,” the NMBU professor said when the book was launched.

According to Sverdrup-Thygeson, it is well known that plants secrete chemical substances, for example, when they are attacked by insects.

But such a biochemical reaction is certainly not the same as a feeling of pain, she points out.

A very interesting debate

“The debate that is now brought up through the new article by Karst and colleagues actually touches on a much larger and very interesting debate. Namely, how research is communicated to a wider audience, how much humanisation is okay, and how we look at forests and nature,” Sverdrup-Thygeson says.

She emphasises that fungal networks are not her field of research.

But she has written several popular science books about nature. Books that have sold a lot.

“What I have experienced is that there can be a delicate balance between making research understandable and tipping over into the ‘Disneyfication’ of research results,” she says. “Oversimplified communication can, at worst, be dumbed down and misleading. Such exaggerated claims can also get in the way of what I believe is a genuine understanding of how incredibly fascinating the forest and nature really are.”

Love between trees

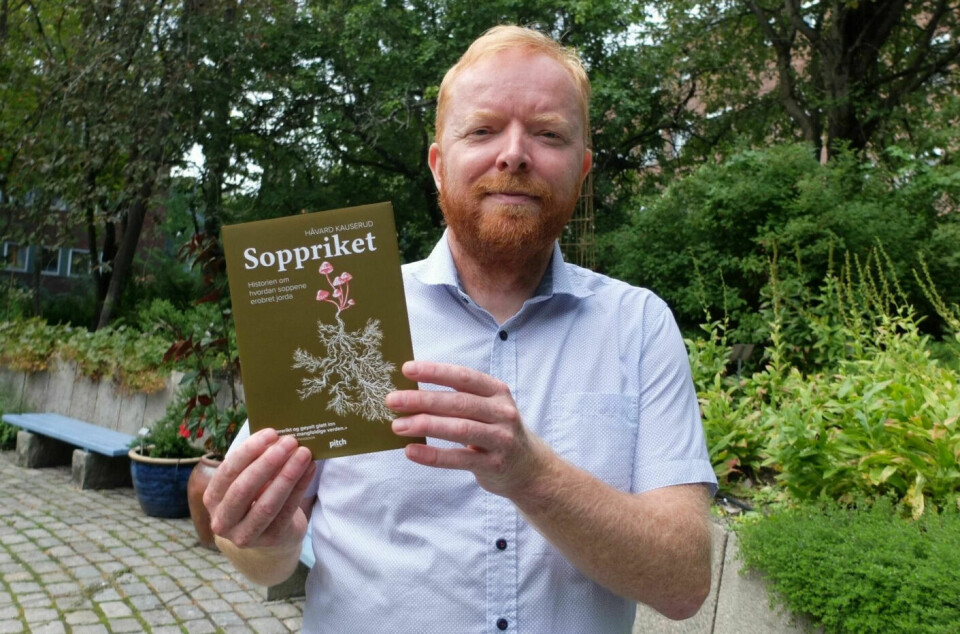

Håvard Kauserud is a professor at the University of Oslo and specialises in ecology of fungi.

“Fungal networks underground are extremely difficult to research,” he tells sciencenorway.no.

Kauserud clearly sees that there is cherry-picking in Wohlleben's book The Hidden Life of Trees.

“Everyone involved in this agrees that it is an important and very interesting research field. And several of the ideas of Suzanne Simard and Peter Wohlleben are not necessarily wrong. But they are difficult to document,” he says.

Talking about ‘love’ between trees seems rather out of place to the specialist in fungi and underground fungal networks.

“But several of these theories are not necessarily just nonsense,” he says.

Doesn't believe trees can feel pain

Håvard Kauserud does not believe that trees are able to feel pain.

“If you damage a tree, biochemical reactions are set in motion. Just like when we damage our skin. Something biochemical happens in both trees and people. Some might even call what happens in trees ‘pain’. But it’s just quibbling over words,” Kauserud says.

He thinks it is good that other researchers are now examining the theories of the Wood Wide Web.

Problem in biological research

Kauserud believes it is a problem within biological research that some generalise too much.

They judge something as being quite certain based on very little research.

“Mycorrhiza (symbiosis between fungi and trees) is now a very large field of research with hundreds of researchers internationally and dedicated journals. There is currently a good amount of research that supports the importance of mycorrhiza networks in nature,” he says. “However, the problem is that it is difficult to find good concrete evidence since it is very difficult to conduct experiments that exclude other alternative explanations of what is observed.”

The point made by Karst and colleagues when they criticise Simard and some other researchers is not that all their theories about mycorrhiza networks are necessarily wrong, Kauserud emphasises.

“Their point is that we have far too few good studies that confirm these theories,” Kauserud says.

The fungal expert at UiO both hopes and believes that the discussion about the popular Wood Wide Web theory will lead to more research on this topic.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Bev Betkowski. Do trees really ‘talk’ to each other through underground fungal networks? University of Alberta, 2023.

Karst et al. ‘Positive citation bias and overinterpreted results lead to misinformation on common mycorrhizal networks in forests’, Nature Ecology & Evolution, vol. 7, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41559-023-01986-1 Abstract.

Luke Taylor. Do trees communicate via a ‘wood wide web’? The evidence is lacking, New Scientist, 2023.

Peter Wohlleben. ‘The Hidden Life of Trees’, Cappelen Damm, 2017.

Suzanne Simard. ‘Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest’, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2022.