The last Ice Age excavated bedrock equivalent to 500 times Mount Everest

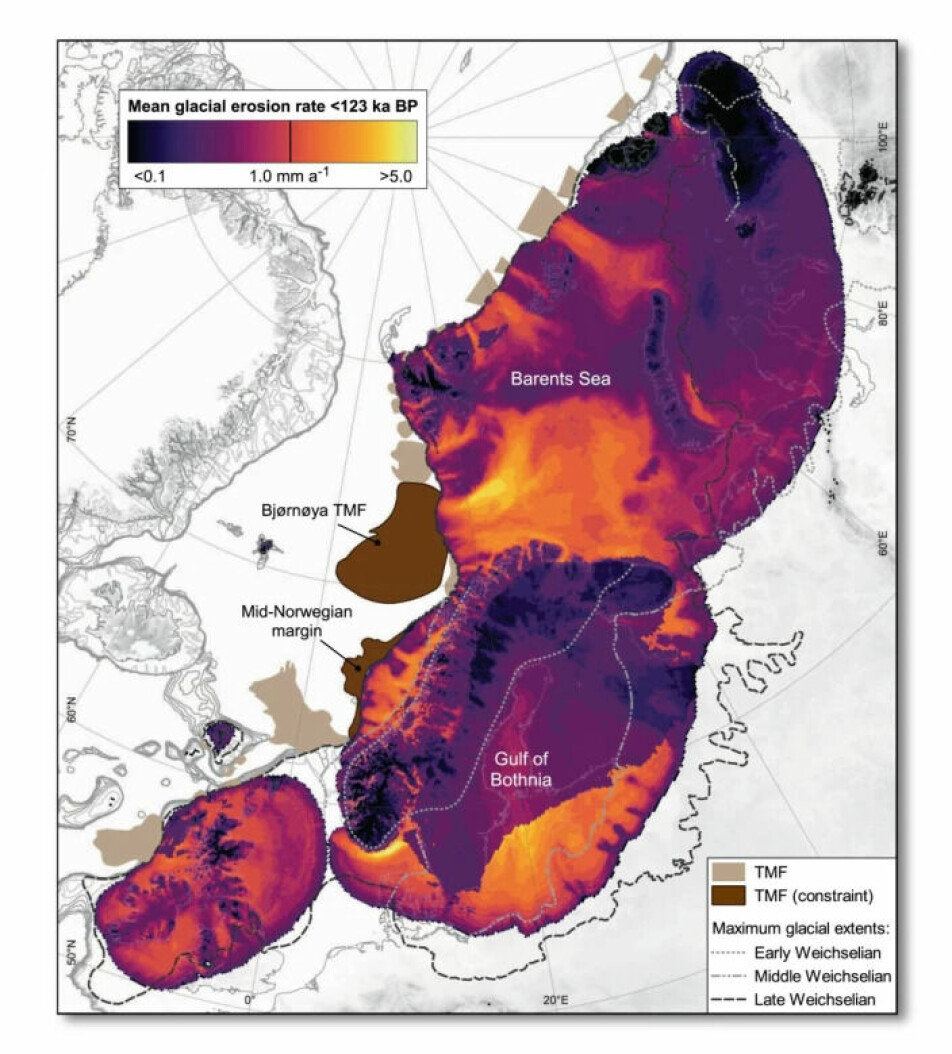

Researchers have calculated how much volume the last Ice Age eroded in Norway and northern Europe.

Around 130,000 cubic kilometres of bedrock. Corresponding to 500 times the mass of the world's highest mountain, Mount Everest.

That’s how much rock disappeared when the ice buried down in Norway and northern Europe – only during the last of many ice ages.

One cubic kilometre is the same as one billion cubic metres.

Protected the mountains

The researcher Henry Patton and colleagues at the Centre for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment and Climate (CAGE) at UiT the Arctic University of Norway are behind these calculations. Their research has now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers have also found something quite surprising: It wasn't our mountains that suffered the most during the Ice Age.

Quite the contrary.

Mountains in Norway, Sweden and Scotland were protected against erosion by the ice, the study shows.

It was in the sea and in the fjords in Western Norway, in Trøndelag and in northern Norway that the ice eroded the most bedrock.

In the sciencenorway.no article below, from this summer, you can read more about how glaciers created the up to 700-metre-deep Norwegian trench. This strange underwater ‘fjord’ was excavated mostly during the penultimate Ice Age, researchers found in another study.

Big differences

The researchers at CAGE in Tromsø have collected many different geophysical data. This is how they succeeded in producing the complex picture of ice erosion that can be seen on the map from their study.

It goes without saying that an ice sheet that was at most 3 kilometres thick must have had a formidable effect on the landscape below.

The researchers found that the erosion was extreme in places such as the Norwegian trench and the Barents Sea.

But in other places it hardly did anything to the landscape. Especially in Norwegian and Swedish mountains.

Heavy erosion at the end of the Ice Age

Through this study, the researchers in Tromsø also observed how the climate and climate change have played a decisive role in the strength of the erosion during the last Ice Age.

Patton and his colleagues conclude that erosion varied greatly during 100,000 years of Ice Age.

For some decades, erosion increased sharply. The study shows that this is connected to the fact that the climate changed and became warmer.

At the very end of the last Ice Age – around 15,000 years ago – the climate warmed very quickly. At that point, erosion increased sharply, the researchers conclude.

“At its peak melting, the Eurasian ice sheet was discharging sediment volumes equivalent to that found in all rivers globally today,” Patton says in an article on CAGE’s website.

All these sediments brought with them quantities of minerals into the sea.

These minerals are nutrients for marine life, which flourished in the aftermath. When this life died, it took with it large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere and was buried under the masses of new sediments that settled on the bottom of the North Sea.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References and sources:

Patton et al., The extreme yet transient nature of glacial erosion, Nature Communications, vol. 13, 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-35072-0

Geoforskning.no: Isens utrolige erosjonskraft (Ice’s incredible erosion power), 5 December 2022.

CAGE: The incredible power of the ice that sculpted Europe's landscape, 1 December 2022.