Can a halted ME study have consequences for other researchers?

A Norwegian ME-study lost its ethics approval due to conflict of interest. Will this decision by a national ethics committee have consequences for other research seeking approval?

Recently, an ME study was halted by NEM, the National Committee for Medicine and Health Research Ethics in Norway. The main reason revolved around the researcher's conflict of interest.

Read about the case and decision here: Controversial ME study loses ethical approval due to conflict of interest

The same study had already received ethical approval from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Trøndelag (REC Mid Norway).

“This is the first time that NEM has reversed a decision from REC based on a financial conflict of interest,” said Camilla Bø Iversen, director of the NEM secretariat.

She reviewed decisions going back ten years and did not find any other cases where NEM had reversed an approval from the regional committees due to commercial interests.

Usually stopped earlier

The reason may either be that the regional committees stop such studies earlier, or that this particular approval was met with complaints. The study was brought to the attention of the national committee due to a complaint from the Norwegian ME association.

Iversen does not disregard the fact that other similar studies may have been approved without an assessment by NEM.

“Before we review an approval, we need to receive a complaint,” Iversen explains.

Thinks regional committees take it seriously

Usually, such conflicts of interest are mitigated or eliminated by reworking the design and protocol of the study at the regional level.

Iversen believes that REC takes this issue seriously when considering applications, but that in this specific case REC and NEM have assessed it somewhat differently.

NEM's decisions can guide REC and the institutions in a later assessment of the question. But conflicts of interest, like all other research ethics considerations, must be considered specifically for each individual case. Cases are never the same, Iversen says.

She notes that researchers may have financial interests, but then the research project needs to be set up and carried out in a way that makes it impossible to question whether the results are influenced by financial interests instead of an objective desire for new knowledge.

“A research project where people might question whether the conflict of interest influenced the results, won’t receive the necessary public trust,” says Iversen.

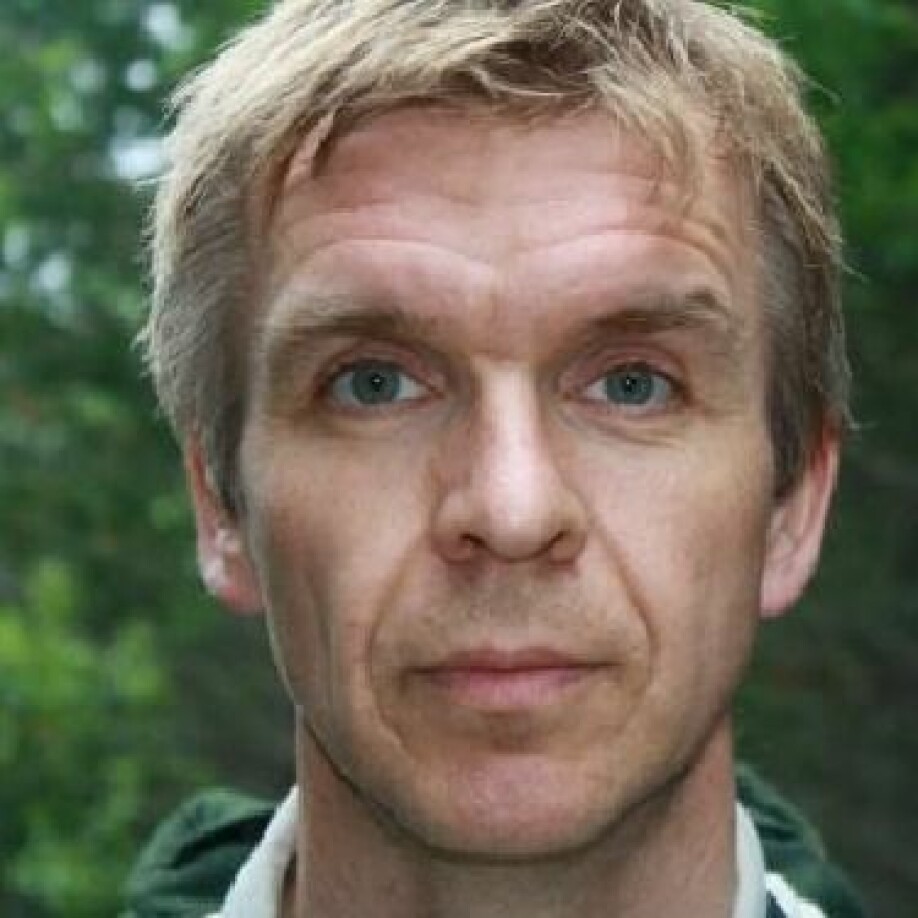

Lars Øystein Ursin, who is an ethical representative in REC Mid Norway commented that it is not at all uncommon for applications to have a conflict of interest by the researcher having a financial interest in the study.

Several rounds of REC evaluation

“We process about 300 cases a year,” says Ursin.

“We run into some of these kinds of issues at every meeting, but they’re in the minority. They often involve product development where a company is part of the study.”

Ursin is an associate professor at NTNU and does research on ethics. He is also responsible for medical ethics in Store norske leksikon, a Norwegian online encyclopedia.

When such cases arise, REC is concerned with ensuring that the research results are not handled in a way that benefits the developer or researcher, from which they could in turn make money, according to Ursin.

“These applications often undergo several rounds with us, where we ask for external monitoring of the results or other measures to alleviate conflicts of interest,” he says.

Somewhat tricky case

Ursin does not consider it a mistake to have approved this ME study.

“We conducted a regular research ethics assessment of whether the conflict of interest was justifiable. The case was a bit tricky, but we treated it very thoroughly,” he says.

He points out that the ethics of such applications are never black and white.

“We acknowledge that NEM came to a different result, but it may indicate that they paid extra attention to the fact that ME is a controversial field,” he says.

Ursin says REC Midt considered this fact as well, “but we came to the conclusion that the study was within bounds.”

Jacob Hølen, head of the secretariat for REC South East, does not have an overview of how much conflicts of interest hinder ethical approval there.

“But I have the impression that denying ethical approval is relatively rare. Sometimes we request more information from the applicant or ask for changes, but usually we end up with an approval. Most researchers are concerned with organizing their projects so that conflicts of interest don’t pose a problem. The researcher can also mitigate minor potential conflicts of interest by being open about any financial ties in their application to us and when publishing,” Hølen says.

Not perceived as a change of course

Hilde Eikemo is the head of secretariat for REC Mid Norway and was the case officer for the ME study.

NEM's denial of ethical approval for the ME study raises the question whether this decision will lead to a change of course for how regional committees process applications where the researcher has financial interests.

Eikemo says NEM's decisions always guide REC's further practice, but she does not regard NEM's refusal of ethical approval as a change of course.

Many applications come from researchers who have financial interests in studies that they are seeking ethical approval for.

Can’t remember denying solely due to financial interests

Eikemo has over ten years of experience at REC Mid Norway and cannot remember that the regional committee has ever refused ethical approval of studies solely on the basis of financial interests.

“It isn’t uncommon for financial interests to be part of the picture in studies – that’s not a sin in itself. But then we tend to set conditions to curb the financial interests,” she says.

REC can request that the recruitment procedure or scientific design be changed, for example.

“When the applicant returns the application with the requested modifications, we might approve it. That’s what happened in this case. We first assessed the application, asked for additional information and outlined deficiencies, and approved it after the applicant provided feedback,” says Eikemo.

She thinks NEM made compelling arguments for their decision. She adds that she does not know what the rest of the regional committee thinks.

“NEM considered the same objections in the application that we did, but weighted them a little differently. NEM seemed to put extra emphasis on the trust aspect in ME research, which is a controversial field,” says Eikemo.

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no