Dispute over Norwegian ME study: What does it actually show?

For five years, researchers have investigated how ME patients experience Norwegian public health services. The study has received a lot of attention and has been discussed in the Norwegian Parliament. But the study also has its critics.

Researchers at the Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research in Norway have conducted a survey among ME patients.

The survey included 660 participants, of which 75 per cent had the ME diagnosis G93.3, while 25 per cent had no diagnosis or other diagnoses.

Participants were asked how they experienced the interventions provided by Norway’s health services, such as psychologists, specialists, and work assessments at the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV).

"On average, the patients experience that most interventions have a low to negative health effect," the study summarising the survey states.

Fafo researcher Anne Kielland wrote in an op-ed on Psykologisk.no that rehabilitation programmes "mostly make patients sicker than they were before".

The study has received criticism from experts on several points.

Criticism 1: Study does not show whether patients have become healthier or sicker

“In order to say that patients have gotten sicker or healthier from an illness, a study must be set up very differently, so the Fafo study can’t comment on this point,” physician Ingrid B. Helland says. She heads the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on CFS/ME at Oslo University Hospital.

None of the participants in the study were working or studying full time.

“The fact that the researchers didn't include those who have recovered or significantly improved from ME means that the population they have studied is skewed,” Helland tells sciencenorway.no. “It’s natural for patients who are still sick to have a more negative experience than those who’ve recovered or are doing much better."

Anne Kielland at Fafo believes that this criticism indicates a misunderstanding of the study's limitations and purpose.

“The main purpose was to look at the service experiences of patients who meet the Canada criteria, in accordance with what the Research Council of Norway asked for,” Kielland says.

“Naturally, we could have included those who were previously sick. But if you're healthy, you'd no longer meet the criteria for the study. Moreover, very few ME patients earn an income equivalent to full-time work. As a result, very few would be excluded from the study, and the criticism has relatively little impact on the results," she says.

Clear on the study's limitations

Sigmund Grønmo, professor emeritus at the University of Bergen, researches and publishes textbooks on social science methodology. He has read the study and the questionnaire – and the criticisms against them.

He believes that the researchers would have learned more if they had included individuals who had recovered from ME.

“That is a clear limitation of the study,” Grønmo says.

Despite this, he believes the criticism levied against the study is quite irrelevant, because the researchers are open about the limitations they have set.

“ The study doesn't provide a complete evaluation of various health services, but exploring the experiences of those who are ill is valuable in its own right. As long as the study focuses on patient experiences, perceptions, and evaluations, then it's fine,” Grønmo says.

In his overall assessment, Grønmo considers the study to be straightforward and honest in its approach and interpretation of results.

The collaborative

project between Fafo and SINTEF has attracted considerable attention.

Questions for Norway’s Prime Minister

Last year, results from the research came up during Question Time in Norway’s Parliament. According to Red Party representative Seher Aydar, the Fafo-SINTEF researchers are concerned, horrified, and report findings that they describe as abusive.

The question to Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre was whether he believes "that the practice of compulsory interventions such as graded exercise therapy and cognitive therapy for ME patients as conditions for assessing disability benefits should continue".

Most viewed

No content

Adaptive training and therapy is one of the treatment options for ME patients.

However, the study does not include experiences with adaptive training, according to Kielland, but participants were asked about cognitive therapy.

Half of the respondents had seen a psychologist. Their experiences were mixed; there were as many who thought it was useful as not useful.

Half of the respondents believed that cognitive therapy was not helpful or had no effect on their symptoms. Only 16 per cent answered that it was positive for their health.

This is not consistent with other studies, according to one of the critics.

Criticism 2: Conflicting results from other studies

Maria Pedersen, a physician at Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet, points out that the findings of the Fafo study conflict with those obtained from clinical patient studies.

“In Fafo's report, participants have many negative experiences with cognitive behavioural therapy. However, such therapy and graded exercise therapy has been found to be effective in other treatment studies," Pedersen says. She is associated with the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on CFS/ME.

In the survey the participants were also asked about two alternative remedies, gammanorm and low-dose naltrexone (LDN). Neither has a documented effect on ME, according to the Norwegian ME Association.

“Here, participants reports many positive experiences, but these remedies haven’t shown any effect in treatment studies,” Pedersen says.

Research on cognitive behavioural therapy, gammanorm, and LDN shows mixed results, and there is ongoing debate regarding the methodologies used, according to Kielland.

Criticism 3: Unclear when patients received treatment

The survey did not ask participants when they used the various health services. Were they in treatment recently or many years ago?

Ingrid Helland finds this problematic.

“There’s no timeline here. How well do we remember events from several years back? Can we accurately assess the impact of an intervention after a long time has passed?” she questions.

The answer to how a treatment works depends on when you are asked.

“For instance, patients might feel tired right after a rehabilitation programme, but over time, they may start applying what they learned. It could also be the other way around, where they feel better right away, but the effect diminishes over time,” Helland explains.

Rehabilitation centres have also changed their treatment in recent years.

"Rehabilitation programmes are very different from what they were 15 years ago," she says.

Sigmund Grønmo thinks that the researchers could have addressed the time factor in their study.

"If some of the participants went through one type of treatment program, while others experienced a different kind, it could influence the study's results. Nonetheless, I don’t consider this critique that important," he says.

“This study investigated ME patients’ experiences with the health services and is not an impact study. Change over time is challenging in surveys as large as this one,” Kielland says.

In upcoming articles, the researchers will examine ME patients' work capacity in the years following rehabilitation programmes, based on Norwegian health registry data.

Criticism 4: The usefulness of a treatment is not the same as perceived health effects

The survey questions about the various health services were not identical.

The participants were asked if some interventions and treatments were useful. For other treatments, participants were asked how the treatment affected their symptoms.

The researchers then grouped the answers into one category: 'usefulness/effect on symptoms'. They did not differentiate between treatments that participants deemed useful and those that impacted their health.

Ingrid Helland considers this approach imprecise.

“There’s a difference between usefulness and effect. Usefulness is also a complex concept. Getting a doctor's note, for example, can be very useful, without necessarily affecting symptoms,” she says.

“Usefulness can mean different things. The researchers have to take that into account when they interpret the responses,” Grønmo says.

Helland has treated many ME patients herself.

“Some of them gained a significantly better level of functioning in the time I followed them up. But they still have just as much pain, continue to sleep poorly, and lack energy. This survey will not capture an improvement in the patients level of functioning," she says.

Loss of precision

Anne Kielland responds that the questions were formulated from qualitative interviews, where the services appeared distinctly different:

“It’s possible that participants might find a treatment to be useful in more ways than for their health, but we believe that ME patients weigh its usefulness based on its relevance to their health and quality of life,” she says.

Sigmund Grønmo believes that designing the questions so that they make the most sense for the resondents is good reasoning.

“The cost of doing so is reduced comparability," he says.

Precision was lost when researchers combined two questions, according to Grønmo.

“They could have been clearer about why they varied the questions and response options and that the consequence is that they can’t compare the patients' experiences with the different services,” he says.

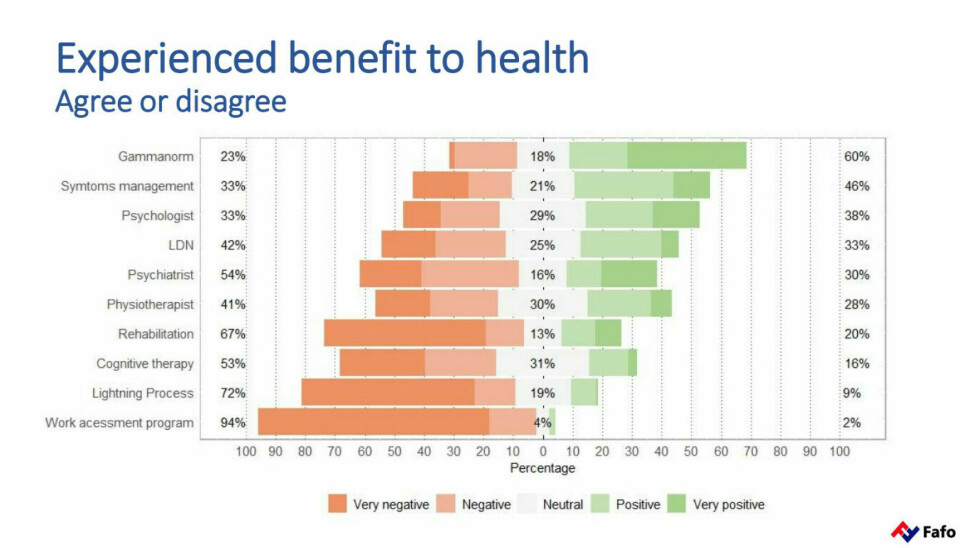

At the seminar where the research was presented, however, a comparison of the health services was made, as indcated in the diagram below.

According to Kielland, this was a simplification in a heading in a PowerPoint presentation.

“The most precise approach is to distinguish between the questions where we ask about usefulness and where we ask more directly about effect,” she says.

She understands the point about comparability – yet:

"Even though we believe we have chosen the most meaningful way to phrase each question, comparison is most natural if you free yourself from the impact study approach and realise that this study is about comparing patients' positive and negative experiences with the different forms of services,” she says.

Criticism 5: Unclear presentation of the data

The Fafo researchers emphasise that they have not measured the effects of the different treatments.

Yet, Anne Kielland wrote that rehabilitation programmes make patients sicker (link in Norwegian), referring to the data in the project.

But the participants were not asked whether they became sicker from rehabilitation, but whether they improved. 67 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed that the rehabilitation had a positive effect on their symptoms. Only 20 per cent experienced improvement.

However, the qualitative interviews revealed deterioration in the weeks afterward, according to Kielland. Additionally, data from health registries show that relatively few experience an increase in earnings after such stays, and more become dependent on public benefits.

We express our views based on the combination of the survey, qualitative interviews, and the registry data, Kielland says.

Grønmo thinks this is dubious.

“A more correct approach would be to say that the patients believe they’ve become sicker. If researchers use quantitative data, like from the survey, along with qualitative interviews, both types of data should be systematically analysed and presented in context,” Grønmo says.

“Yes, it would be more precise to say that the patients believe they have become sicker. But most studies in the ME field, including impact studies, are based on subjective outcome measures, mostly patient statements,” Kielland responds.

She points out that Statistics Norway presents the results of surveys in the same way. They report that people are doing well in Norway, based on what people answer about how they experience their quality of life.

Other statements from the Fafo researchers, like "patients develop anxiety and a sense of powerlessness in the face of a system that controls their pain," originate from the 22 qualitative interviews, according to Kielland.

"You cannot use qualitative interviews as a backup when asked uncomfortable questions,” Grønmo says.

“No questions are uncomfortable. If there's any ambiguity about the basis of something we've said, it's actually beneficial for us to have the opportunity to clarify such matters. We feel that we’re on solid ground in what we’ve written about this project,” Kielland says.

Criticism 6: Could weaken service options for patients

Ingrid Helland believes that Fafo's study could weaken the health service options for patients.

“We want the treatment programs for this group to improve, but the way these findings are presented, we risk that they become worse,” she says.

However, she also recognises the value of the study.

"The study should act as a catalyst to improve treatment options for these patients, and we must strive to ensure that the patients are met with more knowledge and understanding,” Helland says.

Anne Kielland shares the same goal.

“Our project indicates that substantial public resources are being used on treatment that do little to help patients return to work. We believe this is relevant information for public authorities, and that it in the long term will contribute to improving the treatment and follow-up of a very vulnerable group of patients,” Kielland writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

———

This article was updated 30.01.2024 at 09:12 to include a fact box about ME/CFS.

References:

Kielland et al. Do diagnostic criteria for ME matter to patient experience with services and interventions? Key results from an online RDS survey targeting fatigue patients in Norway, Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 28, 2023. DOI: 10.1177/13591053231169191

Grønningsæter, A.B. (ed.) The service and MEg. Summary report from a project on ME sufferers' encounter with the Norwegian welfare state, Fafo and SINTEF, 2023.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no