Why are we afraid to talk to children about suicide?

Norwegian studies reveal that those responsible for helping children often feel powerless and uncertain.

When Grete Lillian Moen was a teenager, her mother attempted to take her own life. Her mother had been ill for a long time.

As a young girl, Moen believed that it was her fault that her mother became ill. She also felt a heavy burden of responsibility to prevent it from happening again.

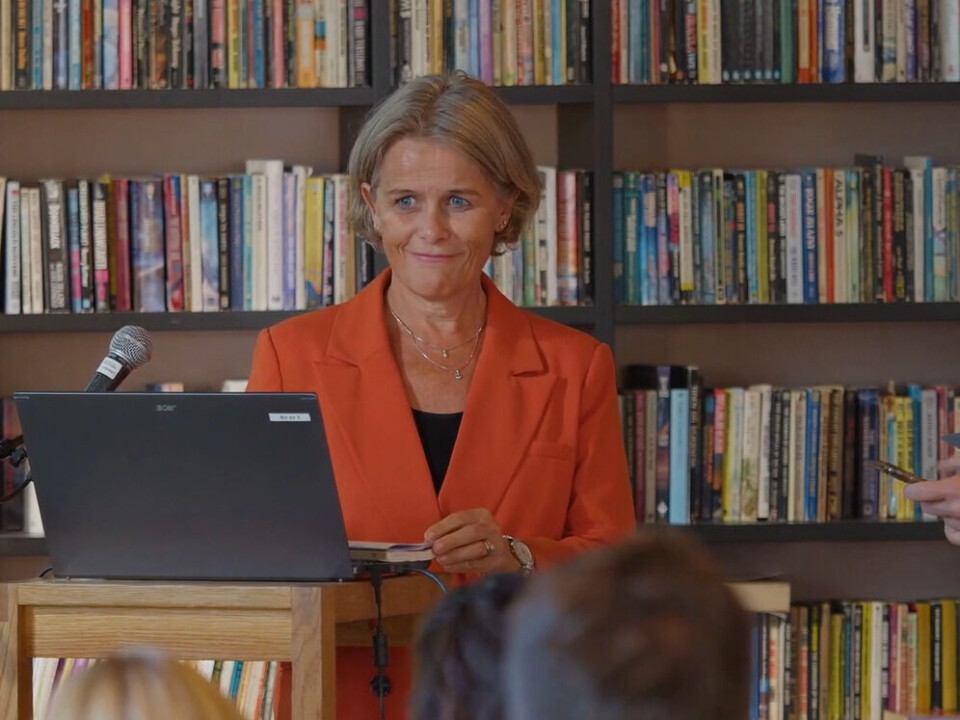

‘I always thought that one day I would tell the world what it's like—what it's like to be a child or teenager in a family when something like this happens,’ Moen shared during a recent lecture at the Literature House in Oslo.

“The helpers are helpless”

Today, Moen works as a special adviser at the Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health (RBUP, where she leads courses on supporting children whose parents struggle with suicidal thoughts or have attempted suicide.

“It's great to be working on this, but at the same time, I'm quite frustrated that it’s taken us so incredibly long to get where we are today,” she said.

Healthcare workers and other support workers often feel powerless, she believes.

“We still have so many excuses for not talking to the children. We still don't understand how or why we should do it. From my experience, it takes very little to make a meaningful difference for these children and adolescents,” said Moen.

“Suicide impacts a significant number of lives”

Around 650 people take their own lives in Norway every year.

“For every suicide, it’s believed there are about ten times as many suicide attempts,” Geir Tarje Bruaset, a researcher at VID Specialized University, said during the seminar.

“If each of these individuals has four or five people close to them, including children, then suicide and suicide attempts impact a significant number of lives,” he said.

Family members of suicidal individuals remain constantly vigilant. The children live in fear of losing their mum or dad.

“Children often assume a great deal of responsibility and try to protect their parents,” said Bruaset.

The routines are lacking

Suicide has long been associated with shame, and children sense this too, says Bruaset. This only worsens their situation.

He has experience as a psychiatric nurse.

“We don’t have proper routines for how to support kids when their parents are hospitalised,” he said.

He is currently conducting a study on what it’s like for children to grow up with a suicidal parent.

Preliminary findings show that suicide attempts are rarely discussed within families and are often masked as another illness.

Children are left to deal with their emotions alone

This was also the case in Grete Lillian Moen's family.

“When mum was hospitalised, dad told us that no matter what happens, we must keep going. That was the only time we ever talked about mum’s suicide attempt,” Moen said.

Children often find themselves alone with their feelings about what happened. Their childhood is shaped by the mental health problems of the adults, and for some, even substance abuse issues.

“When one parent is ill, the healthy parent takes on many responsibilities, while also caring for the sick parent and keeping the family together. This can quickly become overwhelming, leaving little space for the children,” said Bruaset.

Children need support and interventions. But in what way? What works best?

What is the best way to support kids?

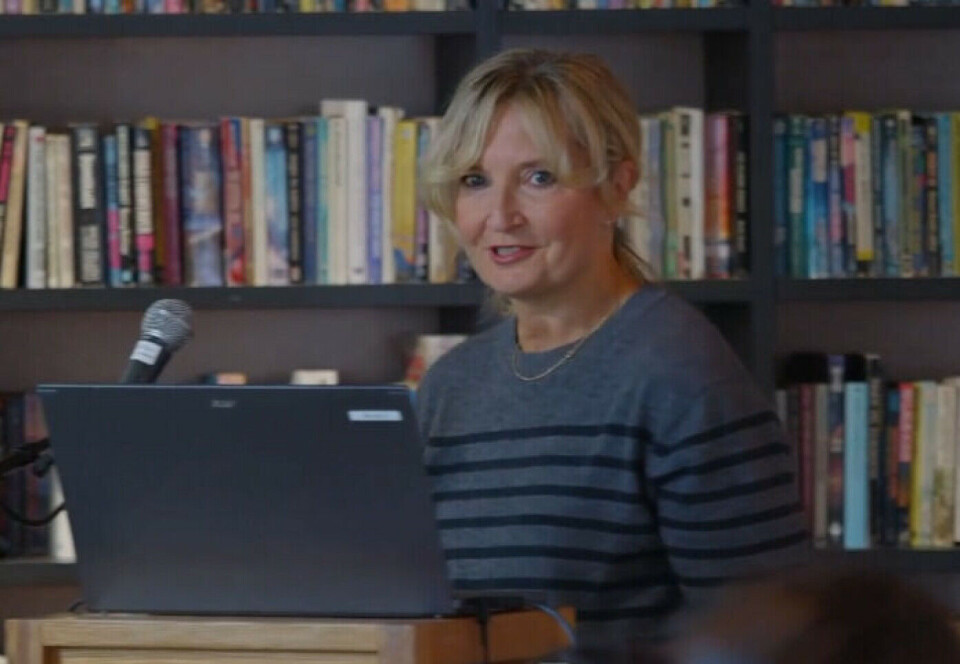

Line Solheim Kvamme, a researcher at RBUP, along with her colleagues, explored international research to find interventions for children of suicidal parents. They wanted to find out if treatments and interventions were effective and beneficial, and how the children and families experienced them.

The results were disappointing.

“We found no studies documenting interventions for children of parents with suicidal behaviour. There’s a massive gap. It’s important, necessary, and effective to offer support to children as soon as their parents are hospitalised after a suicide attempt,” she said.

However, there’s a lack of research-based knowledge on this issue, which Kvamme and her colleagues are working to change.

Support for the helpers

Anneli Mellblom, another researcher at RBUP, shared that a few smaller Norwegian studies have emerged. The findings show that child welfare workers feel powerless, and healthcare workers are uncertain.

To address this, RBUP is developing guidelines for talking to children.

“These guidelines aim to support helpers in how to approach conversations with a child whose parent has attempted suicide,” she said.

It is essential to speak with the child alone, allowing them to ask questions and share difficult emotions without feeling the need to protect their parents.

This needs to be a continuous process. Helpers must also collaborate across disciplines and agencies, according to Mellblom.

No one talked about the suicide attempt

A nurse played a crucial role for Grete Lillian Moen.

The meeting with her mother in the hospital bed was intense. Afterwards, the nurse sat down with Moen and her brother. She explained how their mother had been found unconscious with cardiac arrest, and that they did not know how the extent of her injuries or whether she would recognise her children.

“I’m so grateful for that nurse She provided us with clear, clinical information in such a kind way. That was exactly what I needed at the time," said Moen.

After that, there was silence. No one talked about the suicide attempt. To others, the family explained that their mother had suffered a heart attack.

“If only they knew”

After their mother had been hospitalised for quite some time, they were called in for a family meeting. Suicide was never mentioned.

“They asked how things had been at home while mum was ill. We said everything had been fine. But inside, I was thinking if only they knew about all the crying, the despair, the guilt, and the shame,” Moen recalled.

But Moen could not talk about this. Both parents were present.

“A psychological immune system”

Ida Brandtzæg is a specialist in psychology. She helps parents support their children even when they are struggling themselves.

She pointed out that it’s not the mental health symptoms themselves that negatively affect children, but how those symptoms impact the parents’ ability to function.

For children, having a secure attachment to their parents and caregivers is vital. When children feel safe with adults, they learn how to handle emotions and stress.

“Secure attachment creates a psychological immune system. It’s a powerful form of protection that stays with you throughout life,” said Brandtzæg.

Increased suicide risk for the children

However, some parents are unable to fulfill this role. Those who, because of their own emotional challenges and mental health struggles, can’t be present for their children or understand and meet their needs.

“When parents face these limitations, it can result in insecure attachment. This increases the child's risk of mental health problems later in life, although other factors also play a role,” said Brandtzæg.

Children who witness their parents’ suicide attempts or suicides are at greater risk of attempting suicide themselves later in life.

“But it’s important to note that many kids manage to cope well,” emphasised Geir Tarje Bruaset.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.