Why are researchers so worried about one-year-olds?

Toddlers in kindergartens have elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol, according to a new Norwegian study. But is this really something to worry about?

Most parents of young children in Norway enrol their toddlers in kindergartens. Over 85 percent of all one-year-olds now attend day care.

In the 1980s, children this young were rarely seen in Norwegian kindergartens.

Several researchers who were interviewed are concerned about this development. They believe we should be more careful with children under the age of three – especially because the quality of kindergartens has not kept pace with the increased enrolment.

But not everyone agrees.

Toddlers exhibit more stress

In 2018, Norwegian researchers conducted a study on the stress hormone cortisol in toddlers in kindergartens.

The measurements showed an atypical curve for cortisol levels in one- and two-year-olds, meaning that the levels increased during the day while in childcare and decreased on days the children were at home.

It also turned out that the stress hormone increased most in children who spent eight hours or more per day in a childcare setting.

Findings have been confirmed in a new study

The same trends are also reflected in a new study published in May this year in the European Early Childhood Education Research Journal.

The study found that cortisol levels in children were high in the first week after transitioning to the kindergarten setting. It was still high, but declining, four to six weeks after they started.

The levels were highest in the very youngest children under 14 months. Their cortisol levels after four to six weeks were still as high as during their transition period into childcare.

This could mean that the youngest toddlers need more time to get used to childcare, according to the researchers behind the latest study.

Stress can affect the brain

What does it really mean when researchers tell us that our toddlers are exhibiting elevated cortisol levels?

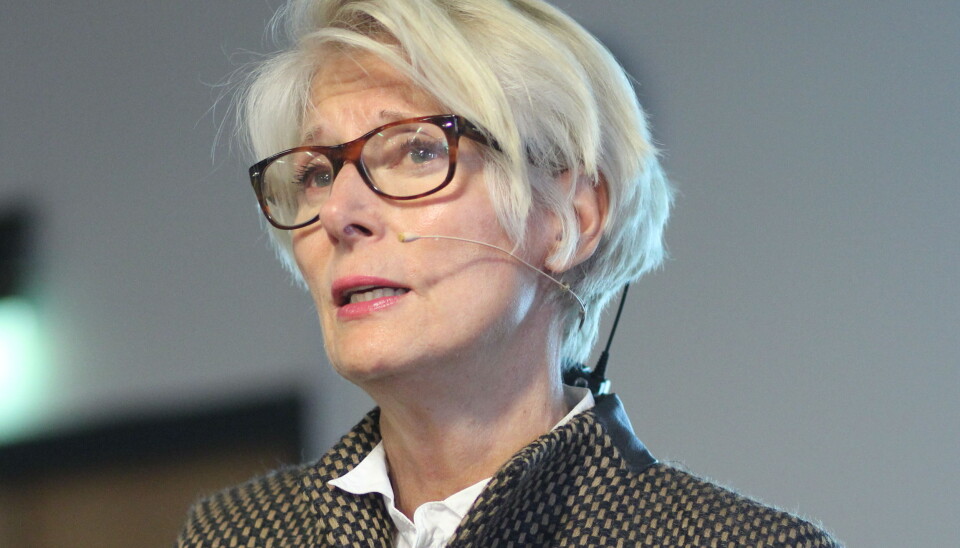

“The youngest children in childcare are the most exposed to stress and the least able to cope with it,” says Turid Berg-Nielsen.

She is a professor at NTNU and the Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health and Welfare (RKBU) of Central Norway, and she was part of the first study on stress in kindergartens.

Berg-Nielsen says that children aged 0 to 2 are at their most vulnerable stage and that they tolerate stress poorly.

“The development of the brain anatomy is in full swing. Negative stress can affect the brain's neurons, and the neurons used to deal with stress reactions are impacted the most,” she says.

Be open to new information

Cortisol is a stress hormone that is found naturally in the body. Cortisol levels rise during stress and fall again naturally afterwards.

Åsa Hammar is a psychologist and researcher at the University of Bergen. She has done a lot of research on adults and found that the system that regulates stress in the body malfunctions in people suffering from severe depression. This failure causes poorer memory, and high cortisol values can in turn lead to a lack of new brain cells forming over time.

Hammar emphasizes that she has not researched toddlers, but she believes it is only natural that children who have higher cortisol levels when starting childcare.

“Whenever we experience something new, cortisol levels increase. The same thing happens to us as adults when we start a new job. It’s part of how the body readies itself to encounter new impressions.”

When you return to a safe environment, your cortisol level drops.

“As long as a child has a safe place to return to, it’s not necessarily harmful to have an increased cortisol level for a period of time,” Hammar says.

But she points out that we still know very little about this.

“This is exciting research that we need to be open to learning more about. But we need more research before we can make conclusions,” says Hammar.

Not worried

Pia M. Risholm Mothander is a lecturer in developmental psychology at the Department of Psychology, Stockholm University.

She has just published the second edition of her book on attachment theory. She notes that little research on childcare for young children is available in Sweden. No similar studies have been performed there on cortisol levels.

“I usually refer to Norwegian research on the topic,” she says.

Mothander thinks it’s good for parents to know that their children experience a higher level of stress when they’re at childcare.

“But I'm not worried about these results. I think they’re pretty obvious,” she says.

Mothander believes this research can be used in the practical guidance of parents.

“They should be aware that it’s important to give their child the opportunity to recover after being at childcare. Have fun together and relax before you start shopping or making dinner. Snuggle on the sofa and look at a book together.

“All parents know that when children have been to a birthday party, they need to calm down afterwards. But this doesn’t mean that it’s dangerous to go to birthday parties,” says Mothander.

Big differences in quality

In recent years, researchers have documented significant differences in the quality of Norwegian kindergartens.

A study from 2017 shows that the quality of Norwegian toddler groups is consistently above average, especially when it comes to support for children's linguistic, cognitive and social development.

In this study Joakim Evensen Hansen, a researcher at the University of Stavanger, explains that Norwegian kindergartens certainly have room for improvement, but that they are safe and good – and that staff are near at hand and present for the children.

A survey from the OECD in 2015, on the other hand, shows that Norwegian kindergartens' offerings are inconsistent.

Some children more affected than others

All children are affected by poor childcare quality, but some more strongly than others.

“This is an important research field in developmental psychology today,” says psychology specialist Stig Torsteinson.

“This research shows that low-quality kindergartens especially affect children with temperamental challenges, both the ones who are quiet and introverted and those who are impulsive,” says Torsteinson.

These children would benefit significantly from measures that address better relationship quality between the children and the adults.

Children who have experienced insecurity would also especially benefit from good relationships.

“Kindergartens should be providing children with more and more positive contact experiences. Over time, and as the good contacts increase, they can replace the insecurity. Traces of trauma and lack of care in the nervous system eventually become less prominent.”

Torsteinson heads the Attachment-Psychologists' education centre and clinic with Ida Brandtzæg.

Qualities of good childcare

All the researchers interviewed by Sciencenorway.no consider high-quality kindergartens important. Inadequate childcare can negatively affect the children.

So what qualities make a good nursery setting – and for that matter, what makes a bad one?

According to the researchers, the most important characteristics of a high-quality kindergarten are the size of the groups – how many children per adult – and stable, well-qualified and adequate staff.

Toddler groups should have no more than ten children and at least one employee per three children throughout the day. Kindergartens should avoid shared positions to limit the number of adults that children have to relate to, according to the researchers.

“Most kindergartens in Norway aren’t high-quality kindergartens. They’re about average,” says Berg-Nielsen.

However, some researchers disagree. Kindergarten and childcare researcher Lars Gulbrandsen, for example, is sceptical of a study indicating that several Norwegian kindergartens are inadequate. He believes that kindergartens (which include toddlers) in Norway have improved in recent years.

Unwilling to prioritize the littlest ones?

“The first three years of a child's life are much more formative than previously believed. And we – as a society – haven’t smoothed the way enough for families with young children,” says Berg-Nielsen.

She finds it paradoxical that Norway does not have more high-quality kindergartens.

“Norway has been more concerned with quantity than quality. For the last decade politicians have been saying that we have enough kindergartens and now we need to work on quality, but it’s slow,” says Berg-Nielsen.

She believes society is not willing to prioritize the youngest children.

Believes ambitions should be higher

Berg-Nielsen is not the only one who is worried.

“There’s room for improvement when it comes to giving young children a good start. Because our society is the way it is, in the foreseeable future young Norwegian children will likely benefit from the full efforts being made to develop even better childcare offerings adapted to their unique needs,” says May-Britt Drugli, a professor of pedagogy at NTNU.

She believes the ambitions for a country with almost full kindergarten coverage should be good kindergartens for everyone.

“Providing good quality childcare needs to be combined with greater freedom of choice for individual families,” Drugli adds.

“Time and time again, the quality of the kindergarten is pointed out as an important factor. We know that kindergarten quality for the youngest means caring, warm adults who have a solid understanding of young children's needs. In addition, they stimulate young children's curiosity and desire to learn. We also know that this quality of interaction is generally only middling in Norwegian kindergartens and therefore not good enough,” says Drugli.

Not everyone equally negative

Not all the researchers interviewed hold a negative view of starting kindergarten early.

When asked if kindergartens are good for children under the age of three, OsloMet kindergarten researcher Anne Greve says, “This question is as old kindergarten itself, and from time to time such questions arise. Fortunately, it’s quite well documented that high-quality kindergartens are good even for children younger than age three.”

“Every person is different, and it matters which child you’re talking about, which kindergarten, not to mention what the alternative would be. So I think it's more interesting to discuss what a good kindergarten is than to resume a discussion that creates a black and white picture of either positive or harmful”, she says.

Translated by: Ingrid P. Nuse

———