When the state takes your child

A child custody row between the Norwegian state and an Indian couple living in Norway has caused a big stir. A recently published study reveals when and why social workers split up families.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Last year, Anurup Bhattacharya and his wife Sagarika, an Indian couple living in Norway, lost custody of their children.

Their row with the Norwegian child welfare services has attracted a great deal of media attention and sparked diplomatic action from both India and Norway.

The two children, aged three years and five months at the time, were put in foster care by the local child welfare service. It said the parents failed to take proper care of them.

Families were helped for three years

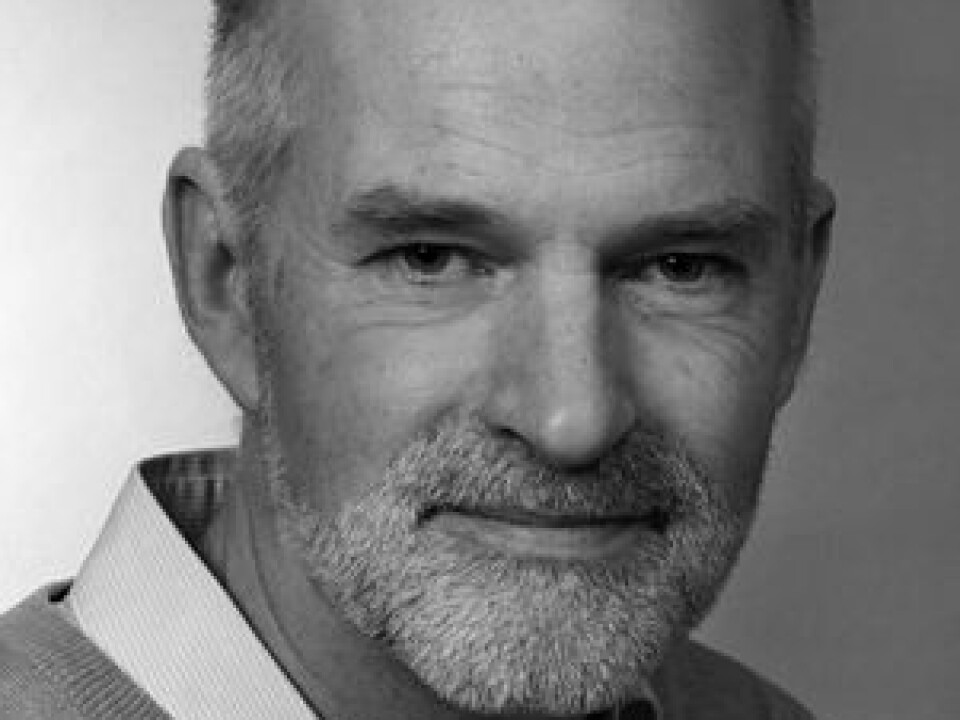

In a study published last year, Øivin Christiansen and Norman Andersen at the University of Bergen surveyed and interviewed 87 social workers in the Norwegian child welfare service.

The two researchers examined 109 cases in which children were re moved from their parents.

Christiansen says that most of these families were well-known to the child welfare service before the crucial intervention was made, and that the families had received help and guidance for an average of three years.

“The children were taken away due to increasing concerns about their situation at home and because the intervening measures didn’t seem to be working well enough,” says Christiansen.

Not always against the parents’ will

The Norwegian child welfare agency aims to teach parents how to take proper care of their children, while also assessing whether or not intervention is necessary.

Christiansen explains that parents often accept the child service’s intervening measures, and that they sometimes willingly give up custody of their children. This applied to about half of the examined cases.

If parents want to keep the custody of their children they can appeal to the local authorities. In some cases where the children's situation is considered unsafe and critical, they are taken away from the home before the trial and kept until the trial is over.

Dirty homes and hungry children

In the interviews, social workers described homes in which parents failed to provide basic, practical care for their children.

Sometimes during their home visits they found that the children were hungry, had poor hygiene and needed clothes and appropriate food.

Some homes were deemed unfit for children as they were untidy and filled with cigarette smoke and bad smell. These houses were described as “chaotic in every sense of the word,” as one social worker put it.

Social workers in the studied cases reported that the children’s behaviour was sometimes different from what was expected for their age – they might be overly introverted or nearly apathetic, showing little curiosity and signs of happiness, and did a poor job with their homework.

In other cases children could act externalised; their disruptive, aggressive, boundless and sometimes scary behaviour caused problems at home and/or in school.

These behaviours were sometimes seen as a consequence of how parents failed to create a predictable framework around their children, and how they struggled to control interactions within the family.

Social workers often described parents’ shortcomings in terms of cooperation, attention, monitoring, control, predictability, and contact.

“The nightmare in Norway”

Earlier this year, the Indian couple fighting the child welfare service were interviewed by India’s largest English language TV station, New Delhi Television. The sequence was dubbed “The Nightmare in Norway.”

The parents denied any wrongdoing and said the child services’ misinterpretation of cultural differences led to the situation, including sleeping in the same bed as the children and feeding them by hand.

The child welfare agency denied this, but has not given an official explanation for their intervention as they are bound through confidentiality outside the courtroom.

Christiansen says that working with immigrant families can be a challenge.

“It’s about what to accept, and what not to accept. What’s culture, what isn’t?”

He adds that there are often language problems, and some families have difficulties understanding how public agencies such as the child welfare service can intervene in people’s lives in Norway.

Criticism of the child welfare service

The child welfare services have been criticised for how their social workers sometimes deal with families from foreign cultures. But the criticism is twofold.

“On the one hand the criticism is about how they don’t consider cultural differences and are ignorant about other cultures,” Christiansen says.

“But on the other hand they’re also criticised for not noticing problems that children experience and for not realising how cultural differences can be used as an excuse.”

Most of the employees at the child welfare service are educated social workers or child welfare pedagogues, and some have a background in psychology or general pedagogy.

Christiansen explains that the Norwegian child welfare agency differs from similar institutions in the US and the UK in that the Norwegian threshold for a family to receive help is significantly lower.

He adds that this, however, has not led to a greater number of intervening measures in Norway.

Back to India?

The Indian government told Norway that it’s important that the children are allowed to return to India as soon as possible. But last month they put diplomatic efforts on hold as the family situation has become a “personal matter between husband and wife,” as junior foreign minister Preneet Kaur told the BBC.

Also last month, the husband was quoted in the newspaper The Hindu as saying “My wife has a serious psychological problem,” adding that he has “concealed the seriousness" within his family.

The child welfare service agency in Norway, meanwhile, was willing to hand over the children to their uncle, who lives in India.

And this week the two children returned to India, after a Norwegian court ruled that their custody should be handed over to their uncle.