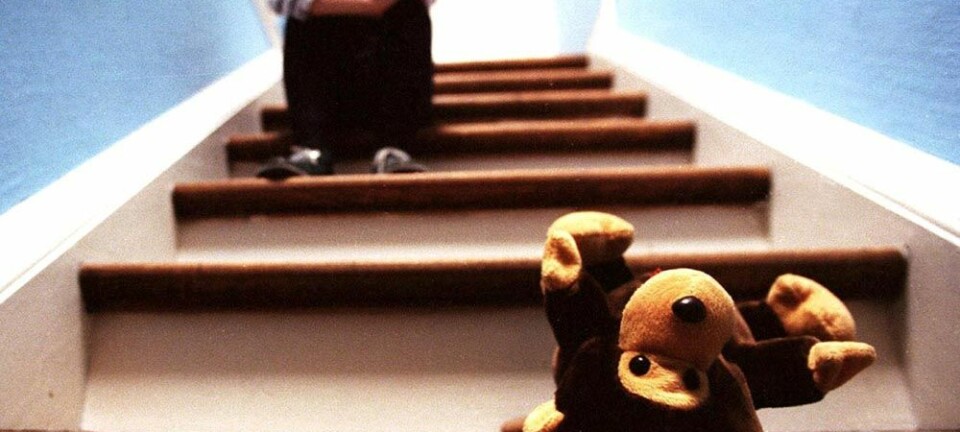

Culture not the main culprit in domestic violence against minority children in the Nordic countries

Children with minority backgrounds are more frequently subjected to violence at home than ethnic Nordic kids. Poverty and social status are stronger contributing risk factors than foreign cultures, according to researchers.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

“Although public attention often highlights the link between minority families and domestic violence, the cultural and ethnic aspects of this became increasingly peripheral as we delved into the problem. Other factors dominate the picture,” says Marianne Buen Sommerfeldt.

Sommerfeldt is a researcher at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies (NKVTS).

Researchers have compared studies of the extent of violence in all the Nordic countries. They looked at conditions which entail risks and at factors which tend to protect minority children from violence. They have also considered how their accrued knowledge can be used among the social services.

Perceptions of reality

The researchers found a disparity between their perception of reality and that which dominated among employees in the social and child welfare services.

Violence against children is disproportionately present among minority groups, according to police and child care authority statistics. At the state-run Children’s House in Oslo, kids with ethnic minority backgrounds comprise a large percentage of those who come to be interviewed because domestic violence is suspected.

“Staff members generally see that minority children are the most susceptible. This is clearly their experience in the field,” says Sommerfeldt.

The statistics from other Nordic countries also indicate that children with minority backgrounds are more likely than their mainstream peers to encounter domestic violence. But the researchers warn against jumping to conclusions.

Slugging, thrashing and shoving

The Norwegian studies in the review show that 80 percent of youth have never experienced being struck by an adult family member. Among those who did report such abuse, most said it only happened once or a few times.

The share of children who are frequently subjected to violence – defined here as more than ten times – was two percent.

Most of the Nordic studies discern between severe and light violence. The more grievous category includes being hit with fists or various objects, being beaten up, etc. Mild violence includes being slapped, shoved around, shaken, pinched or having their hair tugged.

Critical of cultural justifications

Whether a person perceives the problem as large or small will impact how he or she understands it.

This is seen in courts and in cases handled by the Child Welfare Services.

“Many parents think the use of violence in raising their children is normal,” says Kari Stenseng who works in the social services in Norway’s Buskerud County.

“Others are plagued by mental problems, are outsiders in our society or lack self-control. Honour-related violence also occurs, mainly to control the girls in the family,” she adds.

A number of studies have criticised employees in the Child Welfare Service for giving leeway for domestic violence on the grounds of cultural background. This can cause them to overlook serious problems.

Some researchers have also pointed out that the Child Welfare Services risk overstepping in two veering directions. In some instances they can lack an understanding of cultural backgrounds among immigrants and intervene prematurely on behalf of children in a family. Or they can be too lenient the other way and intervene too late.

Sommerfeldt argues that cultures alone cannot explain why minority children are more often mistreated by mothers or fathers than other kids.

“Culture, in the form of values or child-raising methods, established the framework for understanding how families raised their offspring. But it is unacceptable to mistreat children in any cultures.

Culture is not a sufficient justification or explanation,” says Sommerfeldt. Other things play a more important role, such as the family’s financial situation, social conditions and immigration or asylum seeking experiences.

Stress triggers violence

We should therefore look into the stress these families experience, according to the researchers. They can have a high stress level from living in poverty and lacking other people to count on in their daily lives.

In a Swedish study of parents, 34 percent said they had been stressed during their last conflict with a child.

“This stress level often interacts with mental health and the parents’ self-esteem and can affect their capacity as caretakers. This also applies to ethnic Norwegian families,” says Sommerfeldt.

A larger share of minority families live in poverty, have insufficient social networks and are plagued by traumatic experiences. This can explain why they are more prone to engage in domestic violence.

“Wouldn’t some say that you are downplaying the impact of culture?”

“Yes, that could be. But we are concerned about highlighting the nuances. Methodical limitations in the studies we have looked at, as well as the importance of other risk factors than culture, require us to be cautious about explaining violence with ethnicity,” says Sommerfeldt.

“Explaining violence on the basis of a family’s ethnic background is problematic and potentially stigmatizing.”

Sommerfeldt thinks additional knowledge is needed about the role played by culture, with regard to the way social services tackle a family’s problems and the conditions by which violence is used in the upbringing of children.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

Scientific links

- Marianne Buen Sommerfeldt, m.fl: Minoritetsetniske barn og unge og vold i hjemmet - Utsatthet og sosialfaglig arbeid. NKVTS-rapport 3/14. (Norwegian only)

- Svein Mossige og Grete Dyb (red.): Voldsutsatte barn og unge i Oslo. Forekomst og innsatsområder for forebygging. NOVA Rapport 22/09. (Norwegian only)