Soon these will be more popular with young people than birth control pills

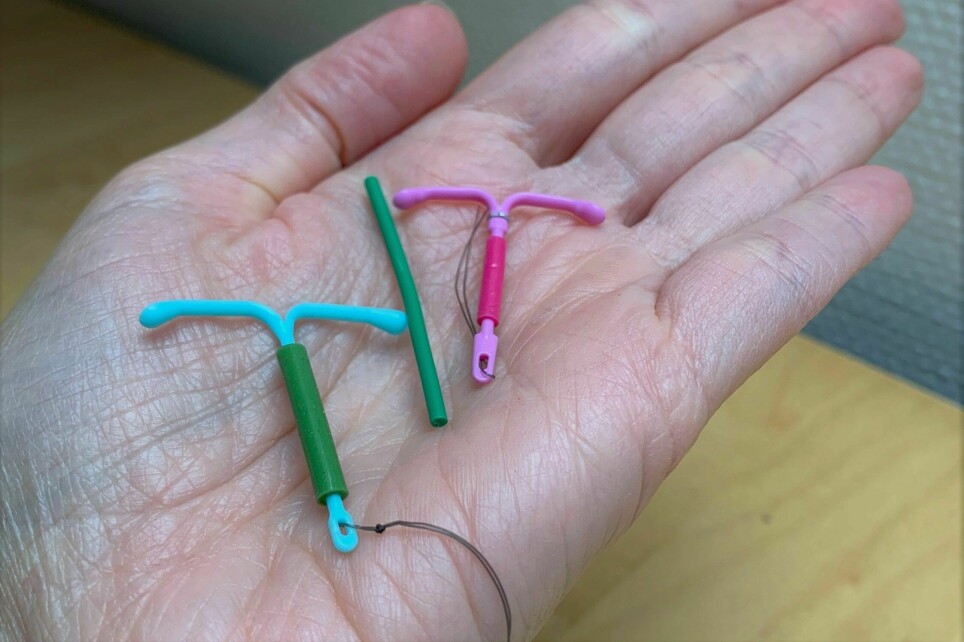

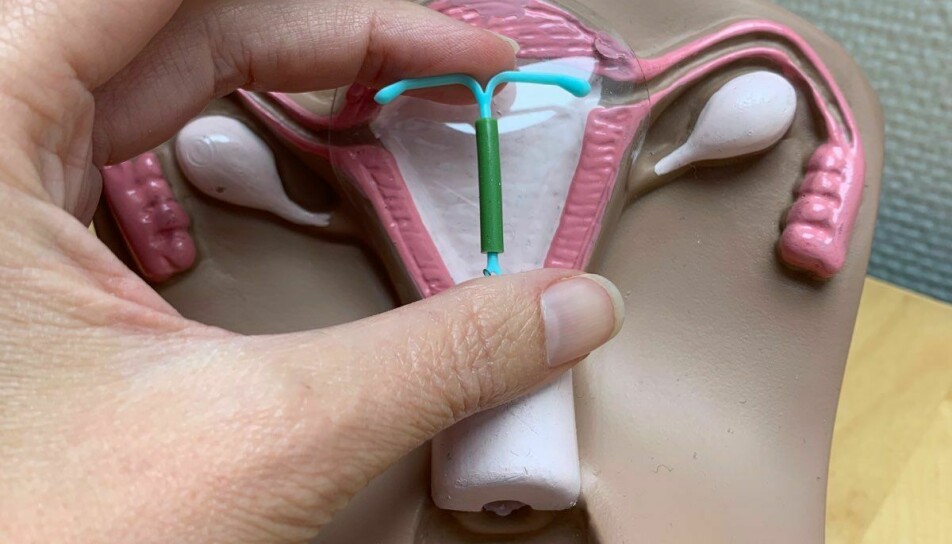

The contraceptive implant and IUD are safer because they don’t pose a risk of blood clots like the birth control pill.

The pandemic has shed light on many different aspects of our lives — including making the side effects of birth control pills suddenly topical again.

"Blood clots as a possible side effect, does that sound familiar?" wrote 19-year-old Maja Bennin Brataas in a young reader’s opinion column on Aftenposten, one of Norway’s largest national newspapers, in the wake of the concerns raised by the AstraZeneca vaccine.

Stories of young women who had ended up in the hospital with blood clots due to their birth control pills abounded in the media.

But even though many young people still use the traditional birth control pill, fewer and fewer are doing so.

At the same time, the popularity of contraceptives and IUDs has skyrocketed, according to a new Norwegian study on the use of hormonal contraceptives from 2006–2020. The study has been published in the journal Norsk Epidemiologi (Norwegian Epidemiology).

Several benefits

In 2015, only six per cent of women between the ages of 16 and 19 used long-acting contraceptives.

In 2020, that proportion had increased to 25 per cent. This is almost the same as birth control pills, which 30 per cent of teenagers use.

One of the researchers behind the new study, Kari Furu, expected to see this kind of pattern.

“I have followed this field for a very long time, so I was not very surprised, but it was a little surprising that it has gone up so much,” says Furu, who is a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Not a coincidence

There are several benefits to these kinds of contraceptives, Furu said.

They contain the hormone progestogen, but not oestrogen, which is found in birth control pills. This reduces the risk of blood clots.

At the same time, the contraceptive implant and IUD offer better protection from pregnancy.

And it’s no coincidence that their use skyrocketed in Norway after 2014, because there were a number of changes that took place around this time.

Free implants and IUDs for the youngest

Doctors were encouraged to recommend alternatives to birth control pills as a way to lower the number of women who developed blood clots.

Beginning in 2015, the contraceptive implant and IUD were free in Norway for 16−19-year-olds, like contraceptive pills had been for several years.

In 2016, another important change took place: Norwegian teens didn’t have to go to the doctor to get contraceptives. School health nurses and midwives were given the right to write prescriptions, and insert and remove both IUDs and contraceptive implants for females who had reached the age of 16.

“That meant that 16-19-year-old girls in upper secondary school who had access to a school nurse also got easier access to long-term contraception,” says Furu.

Clinic overwhelmed by demand

Many Oslo teenagers also get their contraception at a clinic called Sex og Samfunn (Sex and Society).

The centre’s doctor, Trine Aarvold, has noticed this shift among young people.

“Since long-term contraception was made cheaper or free for the youngest women, more wanted it. In particular, the demand for IUDs has exploded in recent years, and we have been overwhelmed by the demand,” Aarvold said.

Old recommendations linger

But even though their popularity has increased among the young, not everyone has realized that IUDs are a good alternative for the youngest patients, Aarvold said.

“The myth that IUDs can only be used after you have had children persists among healthcare professionals. All of the research shows that even the youngest women can use both hormonal and copper IUDs,” Aarvold said.

The old recommendations no longer apply.

IUDs and contraceptive implants should be offered to 15-year-olds

Now Sex og Samfunn wants the government to expand support schemes to make IUDs and implants available to females under 16.

“If you are 15 years old and want a contraceptive implant, you have to pay for it yourself. The problem is that if these girls are not entitled to free contraception, it can be difficult to make contact with those who need guidance,” Aarvold said.

Nerve damage from an implant

However, although IUDs and contraceptives have several benefits, they can have side effects.

Some people experience irregular bleeding. This is also true for the mini pill, which is another alternative to birth control pills that have become more common among young people.

Back and abdominal pain can also be a side effect for those who use IUDs.

And in a few cases, implants have caused serious nerve damage in the arm.

Fewer abortions

At the same time, the popularity of IUDs and implants may have had another, salubrious effect.

“The number of abortions in this age group has fallen at the same time as the use of IUDs and contraceptive implants has gone up. We think this is due to developing good contraceptive practices,” says Aarvold.

Sales of emergency contraception have also fallen sharply in recent years.

Furu also believes that the change in contraceptive practices has led to fewer unwanted pregnancies and reduced abortions among young women under the age of 25, but points out that her study doesn’t enable her to conclude there is a direct causal relationship.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no.

Reference:

Kari Furu et al.: Hormonal contraceptive use in Norway, 2006-2020, by contraceptive type, age and county: A nationwide register-based study, Norsk Epidemiologi 2021, https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v29i1-2.4046