More caution about tongue-tie division urged by researchers

Can tongue-tie lead to breastfeeding problems? Researchers don’t agree on the answer. Some of them urge healthcare professionals to be careful with the surgical approach.

Some children are born with a condition called tongue-tie.

Tongue-tie is when a tight piece of tissue slightly behind the tip of the tongue is attached to the floor of the mouth.

We have this band of tissue because it holds our tongue in place in our mouth.

However, if the piece of tissue is too tight, tongue movement may be too restricted. The limited movement can create problems for language development, causing some letters to be difficult to pronounce, according to Norwegian Health Informatics.

Some people claim that tongue-tie can also lead to breastfeeding problems.

The simplest treatment for tongue-tie is simply to cut it.

Now Dag Moster, a professor at the University of Bergen and chief physician at the Department of Children and Adolescents at Haukeland University Hospital, fears that clipping the tongue-tie band may become a procedure that health professionals resort to too quickly resolve breastfeeding problems.

Moster recently wrote one of two articles on the correct diagnosis and treatment of tongue-tie in the previous issue of Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening (Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association).

It turns out that this little tongue-tie division procedure is more controversial than you might think.

Breastfeeding problems

One of the biggest disagreements is about breastfeeding.

Many researchers and doctors believe that tongue-tie division is an effective treatment for breastfeeding problems.

The tongue is important when a child is breastfed. It provides a vacuum and, along with tongue movements, is the most important mechanism behind the powerful suction that is required for breastfeeding.

If tongue-tie makes mobility worse, it can lead to problems with both sucking and swallowing, according to the researchers behind one of the articles. Poor suction and being able to hold less breast tissue in the infant’s mouth can result in the mother’s breast not emptying fully and sore nipples.

All of this can eventually lead to mastitis in the mother or the baby getting too little food.

For some mothers, the problem worsens to the point that they have to stop breastfeeding before they really want to, the researchers write.

Controversial diagnosis

“Norway strongly encourages breastfeeding for as many people as possible, which is good,” says Moster.

“But now it seems that tongue-tie is increasingly perceived by health personnel as a cause of breastfeeding problems,” he says.

Both the diagnosis and the treatment have been debated.

“The majority of children with tongue-tie don’t have breastfeeding problems, and children with breastfeeding problems often don’t have tongue-tie,” he says.

Tongue-tie division is on the rise

Moster correctly notes that children undergo tongue-tie division more often now than they used to.

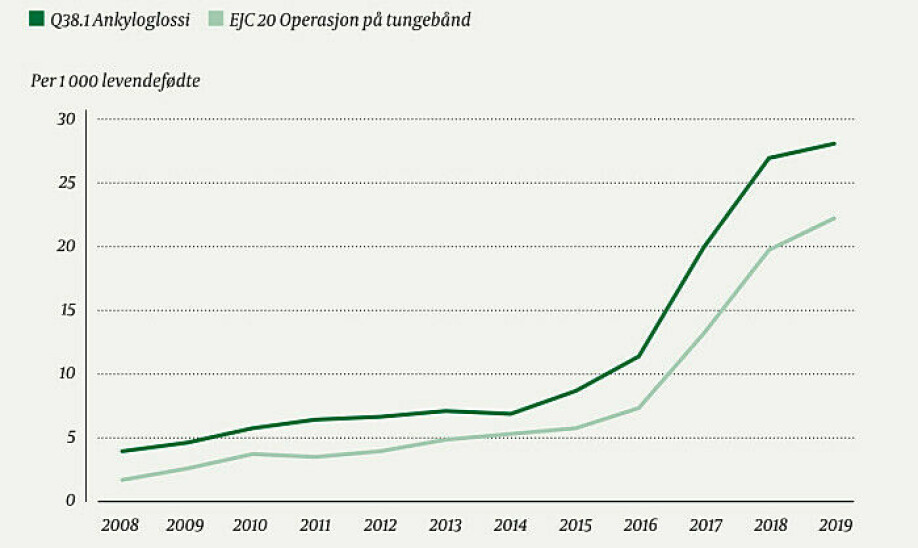

According to the Norwegian Patient Register, 2.8 per cent of new-borns in Norway were diagnosed with tongue-tie in 2019, and 2.2 per cent underwent tongue-tie surgery during the first four weeks of life.

Tongue-tie diagnoses in 2019 were made seven times more often and the procedure was performed 13 times more frequently than in 2008.

Similar developments are taking place in other countries.

Why does the procedure happen more often now?

“The increase could be due to more attention being given to the condition, previous underreporting or a tendency to overdiagnosis in recent years,” says Moster.

Believes many children are unnecessarily clipped

This year, the Norwegian Resource Centre for Breastfeeding developed a new guide for how health professionals should diagnose and treat tongue-tie in infants. This guidance is discussed in Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening (Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association).

Moster and his colleagues believe that the new guidance goes too far in recommending tongue-tie division.

They worry that the recommendation could lead to a further increase in pressure to undergo the clipping procedure.

“Breastfeeding problems in the baby's first weeks of life are very common. It’s important to seek good and knowledgeable breastfeeding guidance and to spend time trying out the guidance given. We should avoid having tongue-tie division become a ‘quick fix’ before time-tested breastfeeding tips have been tried out,” says Moster.

He believes that “when you’re weighing two treatment options – like breastfeeding guidance or tongue-tie division – where there’s little evidence that the surgery is better than the breastfeeding tips, the wisest choice is the alternative that causes the least harm and pain to the child.”

Breastfeeding guidance comes first

The researchers behind the guide emphasize that offering breastfeeding guidance is the first step if they suspect that breastfeeding problems may be due to tongue-tie.

“If a child has tongue-tie that causes breastfeeding or eating problems, breastfeeding guidance needs to be offered. The guide states that when breastfeeding tips don’t help, tongue-tie can be treated by surgery.”

“Infants should only be treated for tongue-tie when there’s an indication,” writes Solveig Holmsen.

She is a doctor and medical advisor at the Norwegian Resource Centre for Breastfeeding.

Guidance doesn’t always work

Holmsen further writes that several of the symptoms of tongue-tie are non-specific.

“Knowledge-based breastfeeding guidance is important so that the more common causes of nursing problems can be dealt with first,” says Holmsen.

However, if the breastfeeding problems are actually due to tongue-tie, breastfeeding guidance alone often does not lead to improvement.

“The cause of the problem won’t be solved, and tongue mobility will still be reduced. Many mothers will still find breastfeeding to be very demanding. A lot of women stop breastfeeding despite having enough milk. In cases like this, tongue-tie division could solve the problem,” Holmsen writes.

A surgical procedure

According to the two journal articles, both the critics and the defenders of the new medical advisor believe that the research on treating tongue-tie is of poor quality and not comprehensive.

“Our goal is to avoid invasive treatment that has poorly documented effectiveness,” says Moster.

Even though tongue-tie surgery is seen as a fairly simple procedure with a low risk of complications, it is still a surgical procedure, he says.

"An irreversible procedure performed on an individual who is not competent to give consent should only be performed after thoroughly assessing the procedure's benefit versus risk and pain for the new-born," he says.

Parents give consent

Regarding consent, Holmsen explains it as follows:

“As with all other medical treatment of infants, the parents' consent is what applies. Mothers who want to give their children breast milk but who struggle due to breastfeeding difficulties require this guidance and help.

She believes the benefit of breastfeeding for the health of both mother and child is well documented.

The experience she and her colleagues have had is that mothers have often struggled with breastfeeding for a long time, and that this increases the risk that they will stop breastfeeding earlier than they want to.

“They might have been treated for wound infection, had several bouts of mastitis and the child wasn’t gaining weight as expected. These are complicated issues that don’t resolve on their own. They need to be followed up with a goal of achieving well-functioning breastfeeding,” she writes.

Meeting criticism

Holmsen says that when it comes to the effect of various measures, such as cutting tongue-ties, randomized controlled trials are regarded as the best research method.

In this kind of study the participants, such as a mother and child, are divided into two groups. One group receives treatment while the other – a control group – does not.

The participants are then followed up over time, and the researchers compare the two groups.

“Very few such larger studies are available,” Holmsen writes.

“Such studies have been attempted, but because parents of children in the control group also wanted their children to receive treatment, researchers found the studies difficult to implement, especially over a long period of time,” she writes.

Due to the dearth of large studies, the knowledge base for the main recommendation in the guide is considered weak to moderate.

“However, the cutting of tongue-tie according to the correct indication is associated with improved breastfeeding through clinical reference works and the overall research from small randomized studies, as well as follow-up studies and descriptions of individual cases of the malformation. In line with recognized clinical guidelines such as UpToDate, the knowledge base is considered sufficient to be able to give a recommendation,” Holmsen writes.

Allows better breastfeeding

Holmsen also points to several ultrasound studies that provide good answers.

The studies show how children with tongue-tie have problems breastfeeding. They also show that the tongue works better after the cutting procedure, so that breastfeeding is improved.

“Several follow-up studies have found that tongue-tie division improves breastfeeding. Randomized studies show an effect in the form of minor pain for the mother, but relatively few children were included and the follow-up was brief,” she writes.

Pain level could be compared to vaccine

According to Holmsen, the degree of pain during the procedure is considered to be low. Here members of the professional community disagree .

“Research and experience indicate that cutting a tongue-tie produces minimal pain. The procedure is small and fast, and the risk of complications is low. Properly done, only the mucous membrane and a thin connective tissue membrane should be cut, and no more than a millimetre deep,” Holmsen writes.

She believes it is important for healthcare professionals who perform the procedure to be able to correctly diagnose and treat tongue-tie.

“Experience has shown that how much the child cries and feels the pain during the procedure can be compared with pain and crying when children receive a vaccine,” Holmsen writes.

She recommends pain relief to prevent and reduce pain, and that the infant should have a small drop of local anaesthetic applied directly to the tongue-tie in most cases.

“Comfort, skin to skin contact with the mother just before and right after the procedure and breast milk before and after are also good practices,” Holmsen says.

References:

Article 1: Solveig Thorp Holmsen et al: Riktig behandling for stramt tungebånd hos spedbarn (Proper treatment for tongue-tie in infants. Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening (Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association), 2021.

Article 2: Ane Charlotte Haug et al.: Stramt tungebånd hos nyfødte (Tongue-tie in new-borns). Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening (Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association), 2021.

———