Life or death chemistry: how scientists analyse mysterious white powders

White powdery substances may be made up of everything from powdered sugar to explosives. We talk to the people in Norway who can figure out the difference.

When an envelope in a mail terminal in Stokke, south of Oslo, burst and released a cloud of white powder, it had serious, unnerving consequences.

Several employees reported burning, itchy skin and difficulty breathing, according to an article about the incident in a national newspaper, VG. The mail terminal was closed and evacuated, and all told, 44 people were sent to the hospital.

While white powder in a package or letter may be completely harmless, sometimes it is not. In 2001, letters filled with deadly anthrax bacteria were sent to US senators and media companies. Five people died and 17 people were injured in the attack.

The powder from the Stokke mail terminal was sent to the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) for analysis. Luckily, it turned out to be a harmless flour product that someone had mailed. The police will now investigate the case, according to Aftenposten, an Oslo-based national newspaper.

But how do scientists actually figure out what is in mysterious, suspicious powders? The Norwegian Defence Research Establishment actually has four different laboratories, each of which has a specific focus on explosives, or biological, chemical or radioactive substances.

A sealed box with gloves

“It can be a little nerve-racking when we get those kind of samples, but we feel safe,” says Jaran Strand Olsen, senior researcher at the FFI, who works in the organization’s laboratory that handles biological threat agents, such as anthrax or plague.

“We have been practicing and have had drills, and we trust our routines,” he said.

By the time they get an unknown substance to be tested, they have already received some information about the sample from the people or institution that submitted it.

The Norwegian Police’s bomb squad will have also already checked to see if the substance is explosive.

It is important for FFI researchers to know what is happening to people who might have been exposed to the unknown substance. If the substance contains infectious agents, it may take hours before people feel ill, while dangerous chemical substances may cause more acute injuries.

They must also treat the substance as if it were contagious or dangerous until they know more about it.

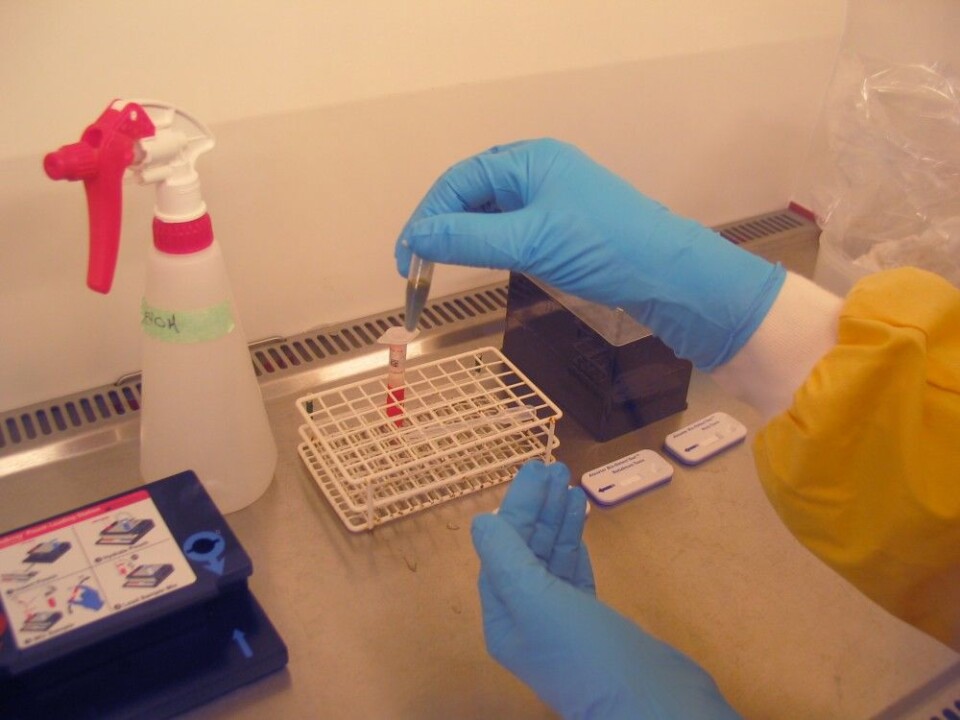

The substance is placed in a sealed box that has gloves built into it. The person who examines the substance also wears an additional layer of protective equipment.

Like a pregnancy test

The first thing that researchers do is use something called handheld test chip, similar to what is used for a pregnancy test.

“You dissolve a little of the sample and put it on a chip, and two lines on the chip indicate whether there is a match,” says Strand Olsen.

Different chips test for different harmful bacteria, including anthrax, tularemia, black plague and toxins, such as ricin. He says that this is the fastest method they use, and it takes between one and fifteen minutes to get an answer.

“This is a good method if you have a pure substance that is at high concentrations,” he said.

A broader survey is called a multiplex assay, where a machine examines molecules in the genetic material of the substance. Scientists use the test to determine if the genetic material matches any known infectious agents, tests for various infectious agents can be run simultaneously. This takes around an hour.

Strand Olsen says they also use more traditional methods, where they grow samples from the substance in petri dishes to see what kind of kind of bacteria it might contain. This takes longer, typically overnight.

From biology to chemistry

The substances are not passed on to the chemical lab until researchers are sure it is free of infectious agents. The researchers can also use detectors to check for volatile, dangerous chemical substances, such as chemical warfare agents.

The sample is then tested for hazardous chemicals, and then sent to a lab that tests for chemical threat agents.

Berit Gilljam is a researcher in the FFI lab that focuses on chemical threat agents. She says they primarily look for substances used in chemical warfare.

“We are also looking for less hazardous substances that can still do damage, such as tear gas or irritants,” she said.

After conducting a few other tests, including checking if the substance is soluble, it is then examined using a technique called infrared spectroscopy, which relies on infrared light to identify groups of chemical substances.

“This works well if we’ve got a clean sample,” Gilljam said. “We can compare the test results with libraries of known substances to find out what it is.”

But if a sample consists of many different substances it can be challenging to interpret the results. Then researchers can use a technique called chromatography, which is able to separate different substances from each other.

“We can almost always find out what the main components of the substance are,” Gilljam said. “If someone has been exposed to the substance, they really want to know what it was. We think it is important to reassure people, so we try the best we can.”

------------------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no