Around 200 Norwegians are diagnosed with the most aggressive brain cancer every year. Now Paal is among the gloomy statistics

Paal Alme had his tumour removed while he was awake. Research is now in full swing on how to eradicate brain cancer completely without surgery.

It was freezing cold in Oslo on January 3 this year. But the temperature did not stop exercise-loving Paal Alme (75) from participating in weekly ski training.

Almost every Tuesday for the past 45 years, he has been responsible for the Ski Association's bare-ground training group in Holmenkollen, the location of a ski jump of the same name and home to many international ski competitions.

On this particular Tuesday, the training ended with a run up the secondary course on the ski jumping hill. Afterwards, in the shower, one of his training companions asked him: “You're completely blue in the face, Paal. Are you feeling well?”

“I feel absolutely fine,” Alme said.

He thought it must be the training and the cold that had done something to the colour of his face.

Mysterious text messages

When he woke the next morning, Alme sent a couple of text messages to his children. Immediately after, his youngest son contacted him.

“What's going on, dad? What you wrote is just nonsense.”

Alme took a look at his mobile. Everything was in perfect order, Alme thought. Alme knows his language — he was former director of communications at the Research Council of Norway and helped start up the Norwegian research news website forskning.no 20 years ago - of which sciencenorway.no is the English version.

The language in the text messages was completely correct. At least inside his head.

Later, he came to understand that those texts consisted of a lot of incoherent gibberish. Nothing made sense, except in his own mind.

About the size of a tennis ball

His son became worried. He asked his father to call a friend who is a doctor. The doctor gave Alme a clear message: Go to the emergency room!

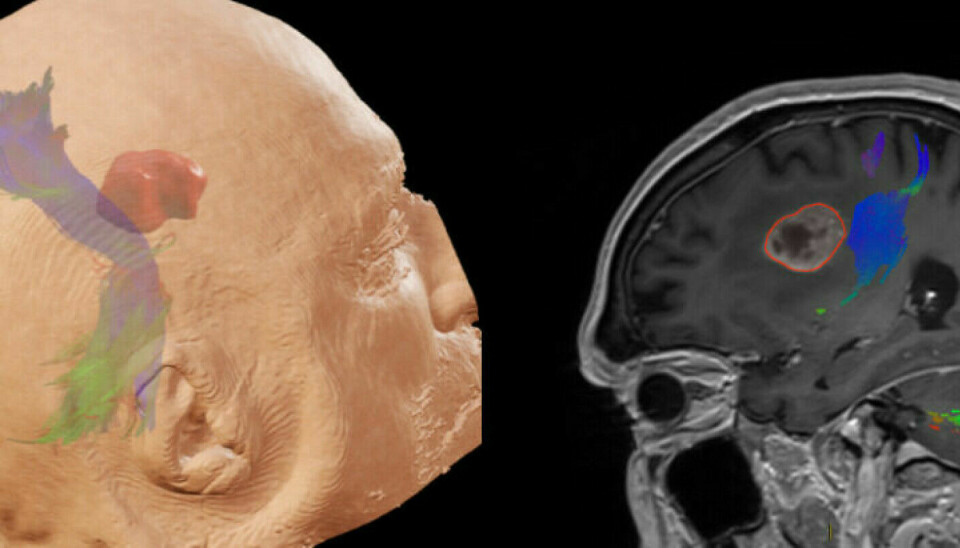

He got into the car and drove himself to Bærum hospital. After a strenuous trip in blowing snow, he was put straight in for an MRI. The doctors found a tumour the size of a tennis ball. It was on the right side of his brain.

The next day, Paal met neurosurgeon Ane Konglund at Rikshospitalet, part of the Oslo University Hospital. She told him he probably had glioblastoma.

Glioblastoma is the worst brain cancer imaginable.

“We will try to take it out. But I want to do it while you're awake,” she told him.

Afraid of damaging his language skills

Alme is left-handed.

Konglund told sciencenorway.no that this was one of the reasons why she wanted him to remain awake during the operation.

“The tumour was on the right side of his brain. Very few people have their language centre there. But there are exceptions, especially among left-handed people. We therefore could not rule out that this might be the case for him,” she said.

Konglund was going to cut into the most vulnerable area of Alme's brain. If she made a mistake, it could have fatal consequences.

That’s why she wanted to talk to him while the operation was taking place.

Can damage healthy tissue

There is one really big challenge for a surgeon who has to remove a cancerous tumour from the brain: To remove as much as possible of the diseased tissue without damaging the healthy part of the brain.

There’s a clear advantage to being able to communicate with the patient during the operation, Konglund said to sciencenorway.no.

For several years, she has performed these kinds of operations at Rikshospitalet with awake patients. But the quality of the operations has steadily improved in recent years, she says.

This is because the operating team has gotten additional tools that make the operation more precise, she says.

A couple of years ago, the operating team was able to start using a contrast liquid that makes the diseased tissue more visible in the brain. The patient drinks a ‘shot’ of the contrast liquid before the operation. This allows the surgeon to see more clearly what is healthy tissue and what is diseased.

In addition, Konglund and her colleagues at Rikshospitalet often use ultrasound, MRI and monitoring of nerve signals during the procedure. They are helped by both neurologists and radiologists during the operation.

“If we approach places in the brain where motor skills are located, we will be told,” Konglund said.

Greater precision

Research shows that all these tools have resulted in more precise operations.

More of the diseased tissue is removed. Less of the healthy tissue is touched.

But all these tools rely on calculations. Nothing is one hundred per cent certain.

“Although the technique may tell us that we have a certain distance to the important pathways in the brain, it will be difficult to say exactly how big the distance is. Every millimetre can be important,” Konglund said.

The key is how the patients feel.

That’s why surgeons want to be able to talk to them during the operation.

Not everyone can be awake

But not all patients can be operated on while awake, as Alme was.

You must be fit enough to withstand the operation and be able to cooperate during the operation, says Konglund.

“In the cases where we have to use full anaesthesia, we unfortunately lose the ability to test the patient's function while awake. Then we have to rely on the aids we have at our disposal,” she said.

Some patients cannot tolerate anaesthesia. The entire operation can then take place when they are awake, with pain-relieving medication, says the surgeon.

Prepared with ‘Grey's Anatomy’

It is January 27. Paal Alme will have his operation today.

The fit 75-year-old walks into the operating theatre himself. He refuses to lie down in a hospital bed until he has to.

Ahead of him is an operation that will prove to last four-and-a-quarter hours.

Paal has prepared a little. His 20-year-old daughter has been watching the American hospital series ‘Grey's Anatomy’. She has told her father about what goes on during brain surgery while awake.

But first of all there is full anaesthesia. While Paal is completely unconscious, Konglund and her team open up a small window in his head where the tumour is located.

With the opening ready, the patient is woken up again. Then the operation can begin.

The brain does not feel pain

Brain tissue cannot feel pain, Konglund explains.

“As soon as we have put an anaesthetic on the skin and are not working with the meninges and blood vessels, the patient should not be in pain during the operation. We only put a local anaesthetic on the skin and give the patient a sedative so that the patient relaxes and is not stressed during the procedure,” she said.

While his head is open, Paal Alme talks to the operation team the whole time.

He remembers, among other things, that they asked him who he is, where he lives and why he is lying on the operating table right now.

During the procedure, he feels absolutely no pain. But he heard scratching sounds inside his brain, he says.

Konglund says this is completely normal.

“Unfortunately, the patient hears sounds from our tools, such as drilling and suction. If the patient is troubled by the experience, we give the patient earplugs. The challenge then is that it becomes more difficult to communicate along the way,” she said.

The ‘tentacles’ remain

A few days after the operation, Alme is informed that it went according to plan.

They removed the tumour.

But a glioblastoma brain tumour is like a jellyfish. It has tentacles. The surgeon and her team have extracted the jellyfish, but not the tentacles.

These can grow into new tumours. Therefore, they must be treated differently.

When Alme is strong enough, he will be given chemotherapy and radiation to get rid of more of the diseased tissue.

A serious illness

Paal Alme is fully aware that his prognosis for surviving this cancer is poor.

“This is a serious illness,” his surgeon confirms.

“Our aim is to extend the life of the patient, while at the same time we want to retain function. With the treatment currently available, it is not possible to cure this type of cancer,” Konglund said.

Konglund says that a great deal of research is now being done to find better treatments for brain cancer.

Much of this research concerns alternatives to surgery.

Intensive research and several studies looking at alternative treatments are ongoing at Oslo University Hospital. It’s too early to say anything about the results.

New medicine may come

Researchers at the University of Gothenburg, along with French colleagues, have succeeded in finding a new treatment method. It may be able to kill the cancer cells in an aggressive glioblastoma tumour without surgery, according to a university press release.

Using supercomputers and advanced simulations, the researchers have found a molecule that blocks certain functions in cancer cells. An essential feature of the molecule is that it is able to pass through the blood barrier that protects the brain.

The researchers have found that a combination of the new substance and chemotherapy is sufficient to kill a tumour. The treatment is also partially promising in terms of preventing the tumour from returning.

Mice that have received this treatment remained cancer-free.

“These are the first clear results with brain tumours that can lead to a treatment which completely avoids surgery and radiation,” said Professor Leif Eriksson at the University of Gothenburg in the press release.

Has a lot more to do

Paal Alme says that he has come to terms with the fact that he will die.

But he would like to wait a bit.

“I have so much left undone,” he says from his patient room at Stabekk Hospice.

It is here that he welcomes forskning.no, of which sciencenorway.no is the English version. He wants to tell his story to the science news website that he helped start just over 20 years ago and which he headed for the first five years.

“I want to tell people about how wonderful our healthcare system is and how far the research has come,” he says.

But not everything in the Norwegian healthcare system has impressed him.

Cow bells at night

In recent years, he has volunteered quite a bit and been the prime mover for several projects that have given other people a better life.

Even from his room at Stabekk Hospice, he continues this work. Now he speaks on behalf of the dying, so that they will have a more dignified end to life.

In May, Alme appeared in the local newspaper Budstikka and described the shocking conditions at the hospice where he lives.

In recent years, Stabekk Hospice has not had a working alarm system.

“Many people are housed here and are going to die. We have been equipped with cowbells to ring, because the alarm system is not to be trusted. I'm terrified that no one will come when it's my turn,” he said.

After the article in Budstikka, the politicians in Bærum municipality have admitted the error. They say they will take action.

Alme breathes a sigh of relief.

“Going forward, I can concentrate on my own health and try to get healthier and have more time with family and friends,” he said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------